views

Determining What is Being Asked

Break the question down into smaller pieces. Often discussion questions can run long and may actually be multiple questions in one. When answering, you will want to answer all the parts of the question. Look for conjunctions, such as the word “and,” that may be breaking the question into multiple thoughts. It sometimes helps to rewrite the question into its component pieces separately. Then, you can focus on one part at a time. For example: “Using the information from chapters 7 & 8 on emotional intelligence, give your own example that illustrates at least three of the author's main concepts.” Up to the first comma tells you what chapters' information you need to apply to your answer. “[G]ive your own example” lets you know to make up an applicable response that wasn't demonstrated in class already. The last part dictates what the example needs to have, i.e. 3 or more concepts from those chapters.

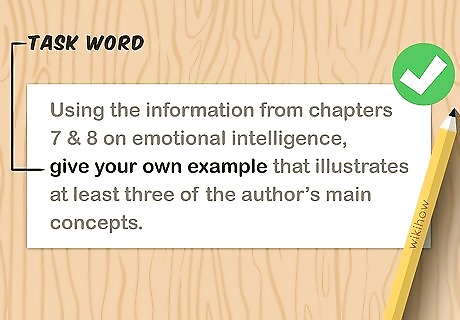

Pick out the task words to know how to word your answer. Some task words are more clear than others. For example, “compare” lets you know there will be multiple items that you have to find similarities between. “Analyze,” on the other hand, can be more abstract. In the above example, “give your own example” would be the task words that show you what the question requires in an answer. There are some great resources that describe what each of these task words means in terms of answering a question—https://web.wpi.edu/Images/CMS/ARC/Answering_Essay_Questions_Made_Easier.pdf has 18 with descriptions of what each word needs you to do.

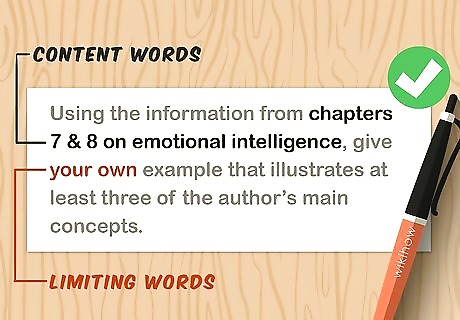

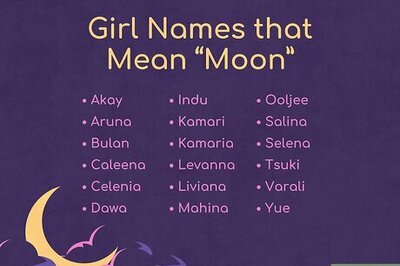

Determine what the other keywords are. There are three types of keywords that can help you to better outline and understand your question—task words, content words, and limiting words. By picking these words out, you can define what the question is asking and how to answer it. Content words are the nouns usually that give you the bulk of what the ideas are about. They will let you know the who, what, when, and where that you need to know about in order to answer. Content words in the example would be “chapters 7 & 8 on emotional intelligence”. Limiting words are often phrases or adjectives that give you hints as to what the question might be looking for specifically. They might seem like filler words, but they are not. Every word in a discussion question is a clue to the answer. Limiting words for the example would be “your own,” which indicates the example should not be one already discussed in the class or text, and “at least three of the… concepts,” which dictates how many concepts you need to apply in the answer.

Ask for clarification if something doesn't make sense. If you don't understand what is meant by a question, take the time to ask. Being on the same page about what you are to answer is crucial to answering a question correctly. Reach out to the teacher or whoever posed the question, if you are able. They will be the best resource for explaining their thinking behind the question. If you're allowed, discuss with classmates or other individuals trying to answer the question. Sometimes a different perspective can help clarify what you might be missing in the question.

Crafting a Thoughtful Response

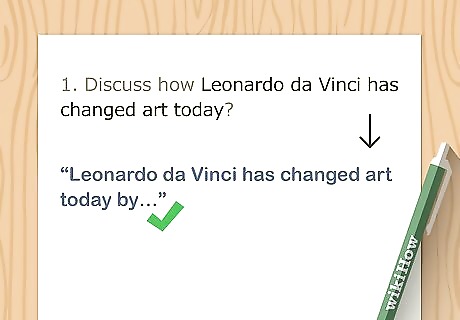

Start by restating what the question has asked. If the question says, “Discuss how Leonardo da Vinci has changed art today?” begin your answer similar to, “Leonardo da Vinci has changed art today by…” This will help show you are answering what was actually asked. This does not need to be a word-for-word reiteration of the question. However, putting the question back into your answer immediately signifies you're on the right track. If you can't do this, you need to go back and start over with determining what the question is asking.

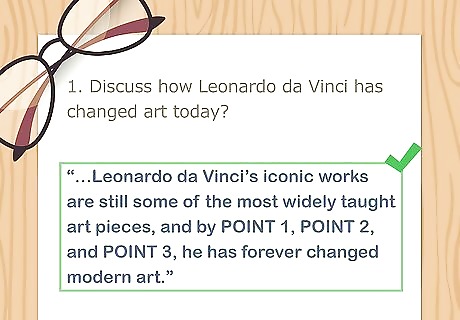

Conclude your introductory paragraph with a thesis statement. A thesis statement will sum up the points you plan to make in the body of your answer, often in list form. It is essentially an outline of the answer in a single sentence. For example: ”Leonardo da Vinci's iconic works are still some of the most widely taught art pieces, and by POINT ONE, POINT TWO, and POINT THREE, he has forever changed modern art.” This introduces the points you would break up into the answer and points back to the question at hand.

Answer in the form that the task word calls for. If you are supposed to “prove” something, answer with facts that connect to each other, leading to the conclusion. Avoid using your opinions unless asked because a proof should rely on the facts presented in the material as opposed to what you believe to be true. That being said, if you can back it up with support from the text or lessons, you will be better off than not having done so. Trace in a discussion question needs you to make chronological connections between two events. Define not only wants you to create a clear description of a topic or idea but wants you to back that up with context and material that lead you to that conclusion. Outline is a chance to break up the question into major components. Then add details to each of those major events or points from the lessons. In the da Vinci example, the task word “discuss” is an open-ended opportunity to create an argument for (or against) the notion that he has changed art even in today's world. You could go into how the “Mona Lisa” and “The Last Supper” are still two of the most iconic artworks that are taught even to elementary school children. As an example, continue to expand on the perspective and depth brought to the 2-dimensional world of “The Last Supper” and how that has influenced techniques of perspective in modern art.

Bring in topics and ideas covered in your lessons. Back up the points you have in your answer by the material you have been taught. This shows you have learned and can apply those topics. You can still have your opinions on topics as well, but using the material to support even your opinions is best. ”Why does the author introduce this character?” could be answered by covering the topic of foreshadowing, for example, if the character hints at a similar one later in the book.

Use concrete evidence to back up your claims. No matter what kind of question you're answering, you'll need to back up your assertions with evidence from your material. Lead into it with a phrase like, “One example of this is…” or “We can clearly see this in…”. Sum up the material, analyze it to show how it reinforces your point, and remember to cite properly. Some examples of evidence include: Quotes from the literary work for English class A primary source document or a quote from one, for history class Results from a lab or evidence from the textbook for science class

Touch on all the parts of your question. Just as you broke the question down into its component parts before, you now need to reconstruct it in your answer. If your answer only gets to a part of the question, you still have work to do. If you rewrote your question in smaller questions, go back to each and check off the ones you have covered completely with your answer. Look at your limiting words again and make sure to check off on all of those as well. If you missed out on a clue, your answer might be falling short. In the da Vinci example, you will need to make sure you discuss his artwork, and how that has actually made a “change” to modern art. While da Vinci influenced many fields, you want to answer specific to “art today” by showing there is a change to the techniques or styles from the 1500s when da Vinci lived to now.

Wrap up the response with a summary. The conclusion to your answer should recap the body's main points and point back to how they answer the question that was posed. It helps the reader to briefly review the expanse of your answer in a bite-size chunk.

Polishing Your Response

Give yourself time to edit. As you get better at breaking the question down, you will start to have more time to work on editing. Although you can make a good answer in your first pass, it is very beneficial to get at least one more edit in. Read your answer to make sure it makes sense. Things like the ordering of sentences or paragraphs can be annoying to move, but it can be a great tool to distill your idea further. Check off the parts of your question you've answered, right down to each keyword. If you left out a keyword in your answer, you've left out part of a complete answer.

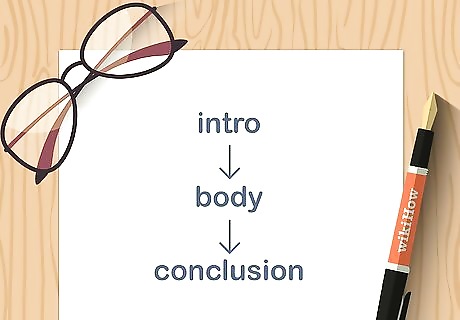

Check that you have a clear intro, body, and conclusion. The intro is going to setup your answer and outline the steps in the thesis statement. The body should answer the task words in a clear but concise manner. The conclusion will restate how this has answered the question, bringing it full circle. Remember to have a thesis statement that outlines the points your body makes in the answer. The body is often be broken up into at least three main parts that answer the question. “Compare” or “contrast” questions may only need two larger parts. The conclusion needs to wrap up your thoughts from the body in a way that brings it back to the question. “These major milestones show why the author believed…” whatever was asked in the question, for example.

Realize there is often more than one right answer. It is easy to feel unsure if you've got the right answer or not, but most discussion questions are going to have more than one right answer. Have confidence if you've followed these steps, and you're sure to get at least partial credit!

Comments

0 comment