views

X

Research source

It can be hard to deal with this disorder for both the person with the disorder and their loved ones. If you or someone you love has Borderline Personality Disorder, there are some ways you can learn to deal with it.

Getting Help for Your BPD

Seek help from a therapist. Therapy is commonly the first treatment option for people suffering from BPD. Although there are several types of therapy that may be used in treating BPD, the one with the strongest track record is Dialectical Behavior Therapy, or DBT. It is partially based on Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) principles and was developed by Marsha Linehan. Dialectical Behavior Therapy is a treatment method specifically developed to help people with BPD. Studies show that it has a consistent success record. DBT focuses on teaching people with BPD to regulate their emotions, develop frustration tolerance, learn mindfulness skills, identify and label their emotions, and strengthen psychosocial skills to help them interact with other people. Another common treatment is schema-focused therapy. This type of treatment combines CBT techniques with techniques from other therapy approaches. It focuses on helping people with BPD reorder or restructure their perceptions and experiences to help build a stable self-image. Therapy is commonly conducted in both one-on-one and group settings. This combination allows for the best effectiveness.

Pay attention to how you feel. One common problem faced by people suffering from BPD is being unable to recognize, identify, and label their emotions. Taking some time to slow down during an emotional experience and think about what you are experiencing can help you learn to regulate your emotions. Try “checking in” with yourself several times throughout the day. For example, you might take a brief break from work to close your eyes and “check in” with your body and your emotions. Note whether you feel tense or achy physically. Think about whether you have been dwelling on a particular thought or feeling for some time. Taking note of how you feel can help you learn to recognize your emotions, and that will help you better regulate them. Try to be as specific as possible. For example, rather than thinking “I'm so angry I just can't stand it!” try to note where you think the emotion is coming from: “I'm feeling angry because I was late to work because I got stuck in traffic.” Try not to judge your emotions as you think about them. For example, avoid saying something to yourself like “I'm feeling angry right now. I'm such a bad person for feeling that way.” Instead, focus just on identifying the feeling without judgment, such as “I am feeling angry because I am hurt that my friend was late.”

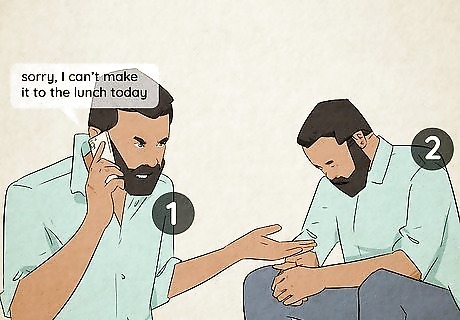

Distinguish between primary and secondary emotions. Learning to uncover all of the feelings you may experience in a given situation is an important step toward learning emotional regulation. It is common for people with BPD to feel overwhelmed by a whirl of emotions. Take a moment to separate out what you feel first, and what else you may be feeling. For example, if your friend forgot that you were having lunch together today, your immediate reaction might be anger. This would be the primary emotion. That anger could also be accompanied by other feelings. For example, you might feel hurt that your friend forgot you. You might feel fear that this is a sign your friend actually doesn't care about you. You might feel shame, as though you don't deserve to have friends remember you. These are all secondary emotions. Considering the source of your emotions can help you learn to regulate them.

Use positive self-talk. One way to learn to handle your reactions to situations in a more healthy way is to challenge negative reactions and habits with positive self-talk. It can take awhile to feel comfortable or natural doing this, but it's helpful. Research has shown that using positive self-talk can help you feel more focused, improve your concentration, and relieve anxiety. Remind yourself that you are worthy of love and respect. Make it a game to find things about yourself that you admire, such as competence, caring, imagination, etc. Remind yourself of these positive things when you find that you are feeling negatively about yourself. Try reminding yourself that unpleasant situations are temporary, limited, and happen to everyone at some point. For example, if your coach criticized your performance at tennis practice, remind yourself that this instance does not characterize every practice in the past or future. Instead of allowing yourself to ruminate on what happened in the past, focus on what you can do to improve next time. This gives you a sense of control over your actions, rather than feeling as though you are being victimized by someone else. Reframe negative thoughts in positive terms. For example, if you did not do well on an exam, your first thought might be “I'm such a loser. I'm worthless and I'm going to fail this course.” This is not helpful, and it isn't fair to you, either. Instead, think about what you can learn from the experience: “I didn't do as well as I hoped on this exam. I can speak with my professor to see where my weak areas are and study more effectively for the next exam.”

Stop and check in with yourself before reacting to others. A natural reaction for a person with BPD is often anger or despair. For example, if a friend did something to upset you, your first instinct might be to react with a screaming fit and make threats to the other person. Instead, take some time to check in with yourself and identify your feelings. Then, try to communicate them to the other person in a nonthreatening way. For example, if your friend was late to meet you for lunch, your immediate reaction might be anger. You might want to yell at them and ask them why they were so disrespectful to you. Check in with your emotions. What are you feeling? What is the primary emotion, and are there secondary emotions? For example, you might feel angry, but you might also feel fear because you believe the person was late because they don't care about you. In a calm voice, ask the person why they were late without judging or threatening them. Use "I"-focused statements. For example: "I am feeling hurt that you were late to our lunch. Why were you late?" You will probably find that the reason why your friend was late was something innocuous, such as traffic or not being able to find their keys. The "I"-statements keep you from sound like you are blaming the other person. This will help them feel less defensive and more open. Reminding yourself to process your emotions and not to jump to conclusions can help you learn to regulate your responses to other people.

Describe your emotions in detail. Try to associate physical symptoms with the emotional states in which you usually experience them. Learning to identify your physical feelings as well as your emotional feelings can help you describe and better understand your emotions. For example, you might feel a sinking in the pit of your stomach in certain situations, but you might not know what the feeling is related to. The next time you feel that sinking, think about what feelings you are experiencing. It could be that this sinking feeling is related to nervousness or anxiety. Once you know that the sinking feeling in your stomach is anxiety, you will eventually feel more in control of that feeling, rather than feeling as though it controls you.

Learn self-soothing behaviors. Learning self-soothing behaviors can help keep you calm when you feel in turmoil. These are behaviors that you can do to comfort and show kindness to yourself. Take a hot bath or shower. Research has shown that physical warmth has a soothing effect on many people. Listen to soothing music. Research has shown that listening to certain types of music can help you relax. The British Academy of Sound Therapy has put together a playlist of songs that have been scientifically shown to promote feelings of relaxation and soothing. Try comforting self-touch. Touching yourself in a compassionate, calming way can help soothe you and relieve stress by releasing oxytocin. Try crossing your arms over your chest and giving yourself a gentle squeeze. Or put your hand over your heart and notice the warmth of your skin, the beat of your heart, and the rise and fall of your chest as you breathe. Take a moment to remind yourself that you are beautiful and worthy.

Practice increasing your tolerance of uncertainty or distress. Emotional tolerance is the ability to endure an uncomfortable emotion without reacting to it inappropriately. You can practice this skill by becoming familiar with your emotions, and gradually exposing yourself to unfamiliar or uncertain situations in a safe environment. Keep a journal throughout the day that notes whenever you feel uncertain, anxious, or afraid. Be sure to note what situation you were in when you felt this way, and how you responded to it in the moment. Rank your uncertainties. Try to place things that make you anxious or uncomfortable on a scale from 0-10. For example, “going to a restaurant alone” might be a 4, but “letting a friend plan a vacation” might be a 10. Practice tolerating uncertainty. Start with small, safe situations. For example, you could try ordering a dish you've never had at a new restaurant. You might or might not enjoy the meal, but that's not the important thing. You will have shown yourself that you are strong enough to handle uncertainty on your own. You can gradually work up to bigger situations as you feel safe doing so. Record your responses. When you try something uncertain, record what happened. What did you do? How did you feel during the experience? How did you feel afterward? What did you do if it did not turn out as you expected? Do you think you will be able to handle more in the future?

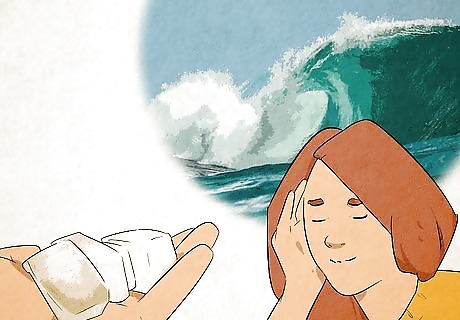

Practice unpleasant experiences in a safe way. Your therapist can help you learn to endure uncomfortable emotions by giving you exercises to do. Some things you can do on your own include the following: Hold an ice cube until you feel the negative emotion pass. Focus on the physical sensation of the ice cube in your hand. Notice how it first becomes more intense and then lessens. The same is true of emotions. Visualize an ocean wave. Imagine it building up until it finally crests and then falls. Remind yourself that just like waves, emotions swell and then recede.

Get regular exercise. Exercise can help reduce feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression. This is because physical exercise releases endorphins, which are natural “feel-good” chemicals produced by your body. The National Institute of Mental Health recommends that you get regular physical activity to help reduce these negative feelings. Research shows that even moderate exercise, such as walking or gardening, can have these effects.

Keep a set schedule. Because instability is one of the hallmarks of BPD, setting a regular schedule for things such as meal times and sleep can be helpful. Fluctuations in your blood sugar or sleep deprivation can make the symptoms of BPD worse. If you have trouble remember to take care of yourself, such as forgetting to eat meals or not going to bed at a healthy time, ask someone to help remind you.

Keep your goals realistic. Dealing with any disorder takes time and practice. You won't experience a complete revolution in a few days. Don't allow yourself to get discouraged. Remember, you can only do your best, and your best is good enough. Remember that your symptoms will improve gradually, not overnight.

Dealing with a Loved One Who has BPD

Understand that your feelings are normal. Friends and family members of those who suffer from BPD often feel overwhelmed, divided, exhausted, or traumatized due to their loved one's behavior. Depression, feelings of grief or isolation, and feelings of guilt are also common among people who have a loved one with BPD. It can be helpful to know that these feelings are common, and aren't because you are a bad or uncaring person.

Learn about BPD. Although BPD is as real and debilitating as a physical illness. The disorder is not your loved one's “fault." Your loved one may feel intense shame and guilt about their behavior, but feel unable to change. Knowing more about BPD will enable you to give your loved one the best support possible. Conduct research to learn more about what BPD is and how you can help. The National Institute of Mental Health has a wealth of information on BPD. There are also many online programs, blogs, and other resources that can help you understand what it is like to suffer from BPD. For example, the National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder has a list of family guidelines. The Borderline Personality Disorder Resource Center offers videos, book recommendations, and other advice for loved ones.

Encourage your loved one to seek therapy. Understand, however, that therapy may take some time to work, and some people with BPD do not respond well to therapy. Try not to approach your loved one from an attitude of judgment. For example, it is unhelpful to say something like “You're worrying me” or “You're making me weird.” Instead, use “I”-statements of care and concern: “I am concerned about some things I've seen in your behavior” or “I love you and want to help you get help.” A person with BPD is more likely to find help from therapy if they trust and get along with the therapist. However, the unstable way that people with BPD relate to others can make finding and maintaining a healthy therapeutic relationship difficult. Consider seeking family therapy. Some treatments for BPD can include family treatments with the person and their loved ones.

Validate your loved one's feelings. Even if you don't understand why your loved one feels the way they do, try to offer support and compassion. For example, you can say things such as “It sounds like that is very hard for you” or “I can see why that would be upsetting.” Remember: you don't have to agree with your loved one to show them that you are listening and compassionate. Try making eye contact as you listen, and using phrases such as “mm-hmm” or “yes” as the other person is speaking.

Be consistent. Because people who suffer from BPD are often wildly inconsistent, it's important for you to be consistent and reliable as an “anchor.” If you have told your loved one that you will be home at 5, try to do so. However, you should not respond to threats, demands, or manipulations. Make sure your actions are consistent with your own needs and values. This also means that you maintain healthy boundaries. For example, you may tell your loved one that if they scream at you, you will leave the room. This is fair. If your loved one does start screaming, make sure to follow through on what you have promised to do. It's important to decide on a plan of action for what to do if your loved one begins to behave destructively or threatens to self-harm. You may find it helpful to work on this plan with your loved one, possibly in conjunction with their therapist. Whatever you decide in this plan, follow through.

Set personal boundaries and assert them. People with BPD can be difficult to live with because they often cannot regulate their emotions effectively. They may try to manipulate their loved ones to meet their own needs. They may not even be aware of others' personal boundaries, and are often unskilled at setting them or understanding them. Setting your own personal boundaries, based on your own needs and level of comfort, can help keep you safe and calm as you interact with your loved one. For example, you may tell your loved one that you will not answer phone calls after 10 PM because you need adequate sleep. If your loved one calls you after that time, it's important to enforce your boundary and not answer. If you do answer, remind your loved one of the boundary while validating their emotions: “I care about you and I know you're having a hard time, but it is 11:30 and I've requested that you not call me after 10PM. This is important to me. You can call me tomorrow at 4:30. I'm going to get off the phone now. Goodbye.” If your loved one accuses you of not caring because you do not answer these calls, remind them that you set this boundary. Offer an appropriate time when they could call you instead. You will often have to assert your boundaries many times before your loved one understands that these boundaries are genuine. You should expect your loved one to respond to these assertions of your own needs with anger, bitterness, or other intense reactions. Do not respond to these reactions, or get angry yourself. Continue to reinforce and assert your boundaries. Remember that saying “no” is not a sign of being a bad or uncaring person. You must take care of your own physical and emotional health to properly care for your loved one.

Respond positively to appropriate behaviors. It's very important to reinforce appropriate behaviors with positive reactions and praise. This can encourage your loved one to believe they can handle their emotions. It can also encourage them to keep going. For example, if your loved one begins to yell at you and then stops to think, say thank you. Acknowledge that you know it took effort for them to stop the harmful action, and that you appreciate it.

Get support for yourself. Caring for and supporting a loved one with BPD can be emotionally draining. It's important to provide yourself with sources of self-care and support as you navigate the balance between being emotionally supportive and setting personal boundaries. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder (NEA-BPD) offer resources to help you find support near you. You may also find it helpful to see your own therapist or counselor. They can help you process your emotions and learn healthy coping skills. NAMI offers family education programs called “Family-to-Family,” where families can receive support from other families who are dealing with similar issues. This program is free. Family therapy may also be helpful. DBT-FST (family skills training) can help teach family members how to understand and deal with their loved one's experience. A therapist offers support and training in specific skills to help you support your loved one.Family Connections therapy focuses on the needs of family members separately. It focuses on helping family members strengthen their skills, develop coping strategies, and learn resources that help promote a healthy balance between their own needs and the needs of their loved one with BPD.

Take care of yourself. It can be easy to get so involved in caring for your loved one that you forget to care for yourself. It's important to stay healthy and well-rested. If you are sleep-deprived, anxious, or not caring for yourself, you may be more likely to respond to your loved one with irritation or anger. Get exercise. Exercise relieves feelings of stress and anxiety. It also promotes feelings of well-being and is a healthy coping technique. Eat well. Eat at regular mealtimes. Eat a well-balanced diet that incorporates protein, complex carbohydrates, and fruits and vegetables. Avoid junk food, and limit caffeine and alcohol. Get enough sleep. Try to go to bed and get up at the same time each day, even on weekends. Don't do other activities in bed, such as computer work or watching TV. Avoid caffeine before bedtime. Relax. Try meditation, yoga, or other relaxing activities such as bubble baths or nature walks. Having a loved one with BPD can be stressful, so it's important to take time to care for yourself.

Take threats of self-harm seriously. Even if you have heard your loved one threaten suicide or self-harm before, it is important to always take these threats seriously. 60-70% of people with BPD will attempt suicide at least once in their lives, and 8-10% of them will be successful. If your loved one threatens suicide, call 911 (or the emergency services number for your country) or take them to the nearest emergency room. If you're in the United States or Canada, you can call or text 988 to reach a suicide crisis helpline. Make sure your loved one has this number as well, so they can use it if necessary.

Recognizing Characteristics of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

Understand how BPD is diagnosed. A trained mental health professional will use the criteria in the DSM-5 to diagnose Borderline Personality Disorder. The DSM-5 stipulates that to receive a diagnosis of BPD, a person must have 5 or more of the following: “Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment” “A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation” “Identity disturbance” “Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging” Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats, or self-mutilating behavior” “Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood” “Chronic feelings of emptiness” “Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger” “Transient, stress related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms” Remember that you cannot necessarily diagnose yourself with BPD, and you cannot diagnose others. The information provided in this section is only to help you determine whether you or a loved one may have BPD

Look for an intense fear of abandonment. A person with BPD will experience intense fear and/or anger if faced with the prospect of being separated from a loved one. They may display impulsive behavior, such as self-mutilation or threatening suicide. This reactivity may happen even if the separation is unavoidable, already planned for, or time-limited (e.g., the other person is going to work). People with BPD generally have very strong fears about being alone, and they have a chronic need for help from others. They may panic or fly into a rage if the other person leaves even briefly or is late.

Think about the stability of interpersonal relationships. A person with BPD usually does not have stable relationships with anyone for a significant period of time. People with BPD do not tend to be able to accept “gray” areas in others (or often, themselves). Their views of their relationships are characterized by all-or-nothing thinking, where the other person is either perfect or evil. People with BPD often go through friendships and romantic partnerships very quickly. People with BPD often idealize the people in their relationships, or “put them on a pedestal.” However, if the other person displays any fault or makes a mistake (or even seems to), the person with BPD will often immediately devalue that person. A person with BPD will usually not accept responsibility for problems in their relationships. They may say that the other person “did not care enough” or did not contribute enough to the relationship. Other people may perceive the person with BPD as having “shallow” emotions or interactions with others.

Consider the person's self-image. People with BPD usually do not have a stable self-concept. For people without such personality disorders, their sense of personal identity is fairly consistent: they have a general sense of who they are, what they value, and how others think of them that does not wildly fluctuate. People with BPD do not experience themselves this way. A person with BPD usually experiences a disturbed or unstable self-image that fluctuates depending on their situation and who they are interacting with. People with BPD may base their opinion of themselves on what they believe others think of them. For example, if a loved one is late to a date, the person with BPD may take this as a sign that they are a “bad” person and not worthy of being loved. People with BPD may have very fluid goals or values that shift dramatically. This extends to their treatment of others. A person with BPD may be very kind one moment and vicious the next, even to the same person. People with BPD may experience intense feelings of self-loathing or worthlessness, even if others assure them of the contrary. People with BPD may experience fluctuating sexual attraction. People with BPD are significantly more likely to report changing the gender of their preferred partners more than once. People with BPD usually define their self-concepts in a way that deviates from their own culture's norms. It's important to remember to take cultural norms into consideration when considering what counts as “normal” or “stable” self-concept.

Look for signs of self-damaging impulsivity. Many people are impulsive sometimes, but a person with BPD will engage in risky and impulsive behavior regularly. This behavior usually presents serious threats to their overall well-being, safety, or health. This behavior may be on its own, or may be in reaction to an event or experience in the person's life. Common examples of risky behavior include: Risky sexual behavior Reckless or intoxicated driving Substance abuse Binge eating and other eating disorders Reckless spending Uncontrolled gambling

Consider whether thoughts or actions of self-harm or suicide frequently occur. Self-mutilation and threats of self-harm, including suicide, are common among people with BPD.These actions may occur on their own, or may occur as a reaction to real or perceived abandonment. Examples of self-mutilation include cutting, burning, scratching, or picking of the skin. Suicidal gestures or threats might include actions such as grabbing a bottle of pills and threatening to take them all. Suicidal threats or attempts are sometimes used as a technique to manipulate others into doing what the person with BPD wants. People with BPD may feel aware that their actions are risky or damaging, but may feel completely unable to change their behavior. 60-70% of people diagnosed with BPD will attempt suicide at some point in their lives.

Observe the person's moods. People with BPD suffer from “affective instability,” or wildly unstable moods or “mood swings.” These moods may frequently shift and are often far more intense than what would be considered a stable reaction. For example, a person with BPD might be happy at one moment and burst into tears or a fit of rage the next. These mood swings may last only a matter of minutes or hours. Despair, anxiety, and irritability are very common amongst people with BPD, and may be triggered by events or actions that people without such a disorder would consider insignificant. For example, if the person's therapist tells them that their hour of therapy is almost over, the person with BPD might react with a feeling of intense despair and abandonment.

Consider whether the person often seems bored. People with BPD often express feeling as though they are “empty” or extremely bored. Much of their risky and impulsive behavior may be a reaction to these feelings. According to the DSM-5, a person with BPD may constantly seek new sources of stimulation and excitement. In some cases, this can extend to feelings about others as well. A person with BPD may become bored with their friendships or romantic relationships very quickly and seek the excitement of a new person. A person with BPD may even experience feeling as though they do not exist, or worry that they are not in the same world as others.

Look for frequent displays of anger. A person with BPD will display anger more often and more intensely than is considered appropriate in their culture. They usually will have difficulty controlling this anger. This behavior is often a reaction to the perception that a friend or family member is being uncaring or neglectful. Anger may present itself in the form of sarcasm, severe bitterness, verbal outbursts or temper tantrums. Anger may be the person's default reaction, even in situations where other emotions might seem more appropriate or logical to others. For example, a person who wins a sporting event might focus angrily on their competitor's behavior rather than enjoying the win. This anger may escalate into physical violence or fights

Look for paranoia. A person with BPD may have transient paranoid thoughts. These are induced by stress and do not generally last very long, but they may recur frequently. This paranoia is often related to other people's intentions or behaviors. For example, a person who is told they have a medical condition may become paranoid that the doctor is colluding with someone to trick them. Dissociation is another common tendency amongst people with BPD. A person with BPD experiencing dissociative thoughts may say they feel as though their environment is not real.

See if the person has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). BPD and PTSD are strongly related, as both can arise after periods or moments of trauma, especially in childhood. PTSD is characterized by flashbacks, avoidance, feelings of being "on edge," and difficulty remembering the traumatic moment(s), among other symptoms. If someone has PTSD, there's a good chance they have BPD as well, or vice versa.

Comments

0 comment