views

X

Research source

Therefore, it can be hard to tell the two apart. If you're struggling to tell whether you or a loved one is autistic or has ADHD, you'll want to look for the root of some behaviors, and watch for other behaviors specific to the disabilities - and don't be afraid to consider the possibility of both, too!

Looking for General Signs

Recognize the similarities between ADHD and autism. There's quite a bit of overlap in the presentation between the disabilities, and it is easy to mistake them for each other. Both ADHD and autism can involve: Stimming/fidgeting Difficulty focusing/distractibility Difficulty initiating tasks Creativity Strong emotions; struggling with self-control Not seeming to listen when spoken to Potential hyperactivity or talkativeness Poor coordination Unusual eye contact Social difficulties Sensory and/or auditory processing issues May not show their intellect easily (e.g. underperforming at school) Strong emotional reactions to rejection Self-esteem issues Secondary anxiety/depression

Analyze the person's general focus. Both autistics and people with ADHD may go into hyperfocus (enhanced focus) for long periods of time, especially if the subject interests them. However, people with ADHD usually lose focus due to external or internal distraction, whereas autistic people are more likely to be distracted by external factors (like sensory input). Autistic people may daydream or "tune out" when they're disinterested or are overwhelmed by sensory needs, and may not necessarily look at what they're paying attention to (like with conversations). Without external distractions, their focus is closer to average. They may, however, focus intently on one thing more often and have trouble moving their attention elsewhere. People with ADHD are more likely to daydream or "tune out" even when they're genuinely interested - they may become distracted by their own thoughts. Other things, like people walking past an open door, may also distract them. Both autistics and people with ADHD can hyperfocus, but people with ADHD often struggle to hyperfocus if they're not passionately interested, which is not necessarily the case with autism.Tip: Both autistic people and people with ADHD tend to focus on fun things, like hobbies and video games. Therefore, look for other things as a guide. For example, an autistic student may hyperfocus while doing homework while a student with ADHD may not be able to do so.

Look at disorganization and prioritization. Because both ADHD and autism can come with executive functioning issues, people with ADHD and autistic people can be messy or disorganized, and have difficulty getting things done. While autistic people may have this problem, it's often more intense in ADHD, and it can cause great difficulties with school, work, and self-esteem. Autistic people may not complete a task because they don't know how to do it, or because it doesn't fit into their routine. They may need to have schedules, lists, written instructions, and/or prompting. Someone with ADHD might not complete something because they forget to do it, get distracted by their thoughts or something nearby (like seeing something moving out the window), or procrastinate for various reasons - like disinterest in the task or not knowing how to start. ADHD can result in messiness and misplacing things; the person might often forget where they've put something, or not be able to find it. They may feel like they can never finish cleaning up no matter how much they try. While autistic people can be messy, it's not universal, and they're not as likely to forget where things are. People with ADHD may be constantly late to events and forget to bring important things. This is not as common in autism. Hyperfocus in both autism and ADHD can result in the person losing track of time and forgetting to do something, including self-care.

Think about the longevity of interests. Autistic people are more likely to have long-term, intense interests (called special interests) that they focus on for extremely long times. On the other hand, people with ADHD are more likely to pick up interests on a whim, be obsessed with them for a relatively short period of time, and then drop them.

Consider how much the person talks. Both autistic people and people with ADHD may interrupt and/or talk "at" people and not let them get a word in. Autistic people typically don't realize the other person wants to speak, or have trouble with the give-and-take of a conversation. People with ADHD are typically chatty due to hyperactivity, and interrupt because of impulsivity or overlooking social cues. Autistic people are more likely to "infodump" about their interests and fascinations, and talk quite a lot about them. When discussing topics unrelated to their interests, they may not be as talkative. A person with ADHD might be extremely chatty in general, and talk when they're not supposed to. They may also change subjects or bring up things that seem completely unrelated to others, but make sense to them. (However, not everyone with ADHD is talkative.) Autistic people may have speech delays or difficulty with speech that can make it difficult to communicate verbally, or temporarily lose the ability to speak under stress. This is not present in ADHD.

Analyze the use of movement. While stimming and fidgetiness is common in both ADHD and autism, people with ADHD typically use it to focus or get extra energy out, whereas autistic people also to use it to express/manage sensory or emotional needs. People with ADHD are more likely to be restless and fidgety for no apparent reason, and they might feel the urge to get up when they should stay seated. They may also shift positions constantly, swing their legs in their chair, pick at their cuticles, or fidget with their hair or things in their hands. Autistic people often move around to handle sensory feedback and prevent sensory overload, as well as express their emotions. Their fidgeting may seem more ritualistic or repetitive compared to general fidgetiness, like flicking their fingers or spinning in circles. Both autistics and people with ADHD may fidget or stim to concentrate. They may also stim to express excitement or nervousness.Tip: Don't rely on hyperactivity to distinguish the conditions. Inattentive ADHD (formerly known as ADD) is characterized by little to no hyperactivity, and hyperactivity in ADHD also tends to decrease with age. Autistic people who are under-sensitive to input may also do a lot of sensory seeking behavior, which can make them look hyperactive.

Consider the age of onset. Autism and ADHD are both inborn, but autism tends to show signs in early childhood, even if it's not diagnosed at the time. ADHD, on the other hand, usually presents by middle or late childhood and is very rarely diagnosed in preschoolers. Autism often becomes more obvious under stress, like with more expectations or major life changes (like moving house). An undiagnosed autistic person may be diagnosed later in life due to inability to keep up with expectations or demands. ADHD may become more prominent as the person ages, due to increased demands. For example, they may struggle with the jump to middle school, high school, or college, or have difficulty with keeping a job or steady relationships.Did You Know? Diagnostic criteria for autism requires the traits to be present in early development, whereas diagnostic criteria for ADHD requires the traits to be present before age 12.

Noting Signs of Autism

Look for unusual and/or delayed development. Autistic people often have developmental oddities in several areas (self-care, communication, etc.), which are not present in ADHD. Autistic people may have delayed childhood milestones, reach them earlier than expected, or reach milestones out of order. Autistic toddlers may be late to speak, engage with other people, or potty-train. Later in childhood, they may show difficulty with learning skills like tying shoes, riding a bike, or adapting to more work in school. Teens and adults might struggle with driving, going to college, moving out, or working a job. Not all autistic people are developmentally delayed. Some will reach milestones at the anticipated pace, or even hit them early. People with ADHD may need more time to learn organizational skills and impulse control, but they typically reach childhood milestones at the expected pace. However, they may come across as immature to their peers due to impulsivity, emotionality, and disorganization.

Reflect back on childhood play. Autistic kids tend to play differently from their peers. Instead of acting out pretend scenarios, they tend to play alone and enjoy ritualistic, meditative movements. This is not present in ADHD. Examples of play common in autism include: Stacking, sorting, or lining up toys Focusing on one part of a toy and ignoring the rest of it Reduced or no "pretend play" or roleplaying Repeating or acting out scripts from books, movies, or TV Repeatedly playing games the same way Solitary or parallel play when peers have started playing together Lack of symbolic play (this is when one object represents something else in play) Sensory joyDid You Know? Different play isn't necessarily bad play. It's fun and it can help them unwind and self-regulate. And even if their actions are repetitive, their mind may be busy with thoughts and imagination. So, there's no need to worry or try to redirect it. But you can join in.

Note unusual communication or body language. Autistic people may have different body language, such as rocking or looking away from the person they're listening to. Their communication habits may be quirky and they may also struggle with expressing themselves. Unusual eye contact (e.g. avoiding it, staring intensely, or faking it) Odd or no use of nonverbal cues (pointing, gesturing, etc.) Unusual voice (pitch, monotone/singsong, etc.) Unusually concrete or abstract word choice Trouble with nonverbal communication (body language, facial expressions, sarcasm, subtle hints, tone of voice) Trouble expressing one's thoughts and feelings Facial expressions, tone of voice, or body language that doesn't match with what they're feeling Speech quirks (echolalia, pronoun reversal, very formal or simple speech) Being nonspeaking, or temporarily losing speech, especially under stress

Recognize difficulty understanding social situations. Autistic people tend not to understand many social cues and rules. They may try to do the "right" thing, but they can't figure out what it is. So, they might compensate by mimicking others or researching social skills, but they don't have the same understanding that non-autistics do. It's a lot of guesswork and they may need extra help understanding. Missing social cues Difficulty figuring out what others are thinking and feeling, or in more extreme cases, not understanding that others have different thoughts/knowledge/feelings Not grasping unwritten social rules (personal space, when to speak in conversations) Sincerity, and assuming others are also sincere Not realizing when they did something wrong unless it is explained to them Correcting their behavior once it has been clearly explained to them Being treated like a child by others Preferring to chat with people older or younger than they are, since these people may be more understanding than their peersDid You Know? Both autistic people and people with ADHD can struggle socially. However, while people with ADHD have trouble with inattention or impulsivity, autistic people tend not to understand. Essentially, people with ADHD have trouble actually doing what they know they should do, while autistic people don't know what they should do.

Look for intense, long-lasting interests. Autistic people are more likely to develop special interests. They may hyperfocus on what interests them, focus on learning everything they possibly can about it, and talk extensively about it with others (even if others aren't particularly interested). Unlike non-autistic people's interests, they may have an interest in something very niche, or collect and/or categorize information that most people would ignore. These interests can be about anything - bands, locations, TV shows, castles, various diseases in history, or so on. They tend to collect and organize objects or information related to the interest

Think about the use of routines. Most autistic people thrive in routines, not only because it makes sure that things get done, but because it feels comforting and safe. Autistic people may become upset when a routine is changed or unexpected events occur. People with ADHD may benefit from routines, but do not necessarily enjoy them, and may need help adhering to a routine. Consistency is common in autism. For example, they may order the same food every time they visit a specific restaurant, because they know they like it. Change, such as a favored menu item no longer being available, may be deeply distressing. An autistic person may resist or feel deep discomfort with changes to their routine, even if the change would have minimal to no effect on the result (like drinking out of a different cup). The change feels wrong and distressing. Someone with ADHD isn't likely to resist.

Look at meltdowns or shutdowns. Autistic people may experience uncontrollable meltdowns when overwhelmed by emotions, sensory input, or stress. While people with ADHD can have meltdowns, it usually comes from frustration rather than overwhelm, and it's not as common. Meltdowns may look like tantrums at a glance; they might involve crying, yelling, and throwing themselves to the floor. The person feels "like the world is ending" and can't bear the stress, so they cry uncontrollably. Some autistic people may injure themselves (like hitting their head or biting themselves), and a few might act aggressively (like pushing). Shutdowns look like the opposite of meltdowns. The person becomes passive and may try to hide somewhere quiet to recover. They may temporarily regress and lose abilities, temporarily lose all speech or have trouble talking, and withdraw. Meltdowns and shutdowns are not unique to autism and not every autistic person experiences them, so pay attention to other signs too.

Seeing Signs of ADHD

Look for struggles with attention. People with ADHD often struggle to focus when disinterested, as their minds wander easily. They might stop paying attention or only pay enough attention to get through the task. Autistic people aren't as likely to get distracted when disinterested, and can usually focus better. Signs of trouble focusing might look like: Making and/or overlooking obvious mistakes Procrastinating on or avoiding tasks that require extended focus/sitting still (like homework or paying bills); constantly doing things last-minute Daydreaming and "spacing out" Leaving many projects incomplete Drifting from task to task Struggling to focus, even if they want or need to Taking on more tasks than they're capable of Relying on multitasking to complete things - or, alternatively, being completely unable to multitask

Watch for impulsivity. While autistic people can be impulsive, someone with ADHD is more likely to do things on a whim with seemingly no forethought or planning - whether it's in the short-term (like blurting something out) or long-term (like applying for a job they have no experience in). They're also more likely to engage in risky behavior, like spending money, speeding, drinking excessively, or having unsafe sex. Impulsive behavior can also be physical, like a child who jumps off the couch onto the glass coffee table or a teenager who hits or pushes someone. People with ADHD may be impatient, and have trouble waiting for things. This isn't as common in autism. Teens and adults with ADHD are more likely to struggle with substance use than autistic people or people without ADHD.Did You Know? People with ADHD, particularly children, may impulsively lie to avoid getting in trouble or to get out of something they have difficulty with. Autistic people are less likely to lie or break rules, and tend to be bad liars.

Look for social quirks. People with ADHD usually pick up on social skills, but may overlook social cues or have trouble joining in as a result of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity. Unlike in autism, they typically know what they're supposed to do in social situations - they just have trouble actually doing it. Overlooking social cues (e.g. not seeing someone roll their eyes) Interrupting or talking over others, or "butting into" conversations Blurting out inappropriate comments Talking more than others, and/or trouble letting others speak Changing subjects often, sometimes to the confusion of others "Spacing out" or getting distracted during a conversation Trouble remembering important things (like other people's names or birthdays) Responding emotionally to things (like screaming excitedly or snapping at others) Constantly volunteering to help out with things Difficulty remembering to respond to texts or follow through on plans Having constant excitement or drama in their social circle Being a "social butterfly" or "life of the party"

Notice a love of novelty. People with ADHD tend to have low dopamine. Trying different and exciting things helps. This can mean trying new hobbies, getting excited about new people, and even changing jobs. Once something no longer feels new and exciting, they may move on to the next new thing. This is not on purpose and can be frustrating sometimes. Sometimes, novelty seeking can lead to risk-taking and mistakes. It's important for people with ADHD to enjoy new experiences wisely. In dating, some people may at first obsess over a new romantic partner and shower them with attention, and then get bored once the newness wears off. However, they can find ways to make long-term relationships work. Meanwhile, autistic people tend to limit the amount of novelty in their lives as it can stress them out. They also tend to be more cautious than average.

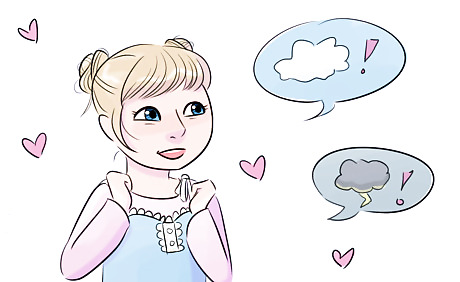

Watch for emotionality. Especially in girls, people with ADHD can experience their emotions very intensely, and have difficulty controlling them. They may become overexcited easily, get easily frustrated, or be devastated by things that don't seem to warrant the response (like being called a name). While autistic people often feel things very intensely as well, they're less likely to react strongly. This can lead to difficulty with professional or interpersonal relationships - for example, children with ADHD might be bullied for crying easily or hitting peers, and adults with ADHD may be short-tempered or easily irritated with others. Strong emotions can make it hard for them to judge what others are thinking and feeling. People with ADHD may be viewed by others as immature, overdramatic, hot-headed, "crybabies", or overly sensitive.

Moving Forward

Consider other possibilities. There are multiple conditions that can look similar to autism and ADHD, and it's ideal to look into other conditions to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis. Conditions and circumstances that can be mistaken for autism or ADHD include... Nonverbal learning disability (which shares traits with both ADHD and autism) Sensory processing disorder or auditory processing disorder (conditions often co-occurring with both ADHD and autism) Learning disabilities (sometimes co-occurring with ADHD) Obsessive-compulsive disorder Post-traumatic stress disorder Anxiety (whether generalized or social) Bipolar disorder Social communication disorder Hormonal imbalances or thyroid problems Giftedness in children

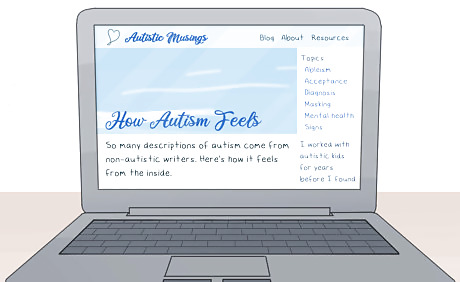

Read what autistic people and people with ADHD have to say. They can bring in a more human aspect to the diagnostic labels, and it may be easier to relate to "I struggle to remember to shower, eat, and go to bed" than "Executive Function Disorder." This can give you a sense of the range of how the disability affects people, and what disability looks like in real life. Try to read from a variety of autistic people and people with ADHD. Autism is a vast spectrum, and there are three types of ADHD (hyperactive-impulsive, inattentive, and combined) that can look different. Both autism and ADHD present differently in girls, and people of color may not be diagnosed until later in life.

Take time to think back on the past. Remember your or your loved one's quirks, defining moments, and remarks from others (such as family, teachers, and coaches). Do any of these start to make sense when viewed through the lens of ADHD or autism? Try to think as far back as you can remember. Subtle signs of autism or ADHD may have showed up in habits that didn't stand out (such as swaying back and forth, always having a messy backpack, or having trouble speaking under stress). Try talking to people who knew you or your loved one in the past, or see if you can find old records that might indicate how you or your loved one behaved (such as report card comments). This can help fill in any blanks. Your ability to get an accurate diagnosis will partially depend on your ability to produce anecdotes describing certain symptoms. Reflecting and being prepared will increase your chances of an accurate diagnosis.

Consider the possibility of both conditions. If most of the traits of ADHD and autism fit you or your loved one, keep in mind that it is possible to have both. If you are autistic, there's a high probability that you may have ADHD also, although the reverse isn't necessarily true. One study suggests that around half of autistic people have been diagnosed with ADHD as well. Similarly, about a quarter of people with ADHD show some signs of autism. Both autistic people and people with ADHD have similar genetic quirks.

Avoid negativity about disability diagnoses. It is possible to be autistic, have ADHD, and be happy at the same time. A disability may present challenges, but it will be okay. Don't let doom-and-gloom predictions frighten you. Disability won't stop a happy future. If your child receives a diagnosis, remember that they can hear you (even if it looks like they aren't paying attention). Vent your frustrations or fears when they are out of earshot. Children shouldn't be worrying about adult problems to an extent, especially if they might think that it's their fault. Be skeptical about fear-mongering rhetoric, such as Autism Speaks ads. These may make it sound like disability will ruin you and your loved one's life. This is not true. Scary words are effective at fundraising, but that does not tell the whole story.

Be very cautious about drawing hard and fast conclusions without a doctor's advice. ADHD and autism are incredibly complex disabilities that can't be understood after a few minutes (or even a few hours) of research. And each person's experience will be different. There is no one simple one-size-fits-all way autism or ADHD impacts a person's life. The Autistic and ADHD community are usually open and welcoming to people who have self-diagnosed after lots of research because diagnosis can be incredibly expensive, sometimes inaccurate, and inaccessible. You will be welcome in the community, but you can't get therapy or accommodations without a doctor's note. Teachers, babysitters and other caregivers can help with noticing signs. However, they can't make an official diagnosis. You'll need to see a specialist.

Get a referral to a developmental disability specialist. Many specialists see autistic patients and patients with ADHD and know a lot about both conditions. You can get a referral from your general practitioner, or from your insurance company.

Bring up concerns about misdiagnosis if needed. If you worry that you or your loved one doesn't have an accurate diagnosis, talk to your doctor or disability specialist. You can also get a second opinion. Doctors know a lot, but they are still human and can make mistakes.

Comments

0 comment