views

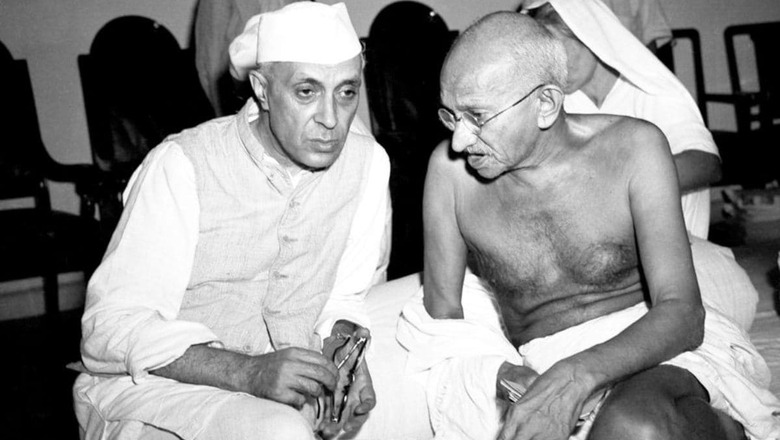

Both Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru believed in writing and airing their differences out in the open, often in rather acrimonious ways.

Nehru, twenty years younger and a self-confessed disciple of Gandhi, had serious differences with Gandhi’s approach towards village economy, non-violence, religion, and economic thinking. In 1945, when the freedom of the country was in sight, Gandhi wrote to him, saying, “I believe that if India is to attain true freedom, then sooner or later we will have to live in villages in huts, not in palaces. The essence of what I say is that the things required for human life must be individually controlled by every person; the individual cannot be saved without this control” (page 14 in Tendulkar D G’s Mahatma, Vol. VII, Times of India Press, Bombay).

As if speaking from a position of strength in anticipation of becoming prime minister of independent India, Nehru was quick to retort in some strong language, “It was many years ago that I read Hind Swaraj, and I have only a vague picture in my mind. But even when I read it 20 or more years ago, it seemed to me completely unreal. It has been 38 years since Hind Swaraj was written. The world has completely changed since then, possibly in the wrong direction. A village, normally speaking, is backward intellectually and culturally, and no progress can be made in a backward environment. Narrow-minded people are much more likely to be untruthful and violent” (page 516 of An Autobiography by Jawaharlal Nehru, Oxford University Press).

More barbs followed as Nehru went on to say, “It seems inevitable that modern means of transport as well as many other modern developments must continue and he developed. There is no way out except to have them. If this is so, inevitably a measure of heavy industry exists. How far will that fit in with a purely village society?” Nehru asked, reminding his mentor, “As you know, the Congress has never considered that (Hind Swaraj) picture, much less adopted it. You yourself have never asked to adopt it except for some relatively minor aspects.” It may be noted that throughout his political life, Gandhi did not hold any formal position in the Congress organisation apart from being the Congress president in 1924.

For Gandhi, non-violence was a weapon of the strong and a non-negotiable political expression that had to be practiced under all circumstances. “Liberty and democracy become unholy when their hands are dyed red with innocent blood” (page 70, New Directions Publishing). But his political heir had a different take. Nehru wrote, “Violence is the very lifeblood of the modern state and social system. Without the coercive apparatus of the state, taxes would not be realised, landlords would not get their rents, and property would disappear” (page 540 of An Autobiography by Jawaharlal Nehru, Oxford University Press). Nehru also had no qualms in telling Gandhi that “democracy indeed means the coercion of the minority by the majority” [the expression majority and minority was in the context of numerical strength rather than the religious identity of communities].

Gandhi wrote to Agatha Harrison on 30 April 1936, stating, “But Jawaharlal’s way is not my way. I accept his ideas about land, etc. But I do not accept practically any of his methods” (cited in Jawaharlal Nehru’s A Bunch of Old Letters, Asia Publication House). Gandhi did not approve of the Nehruvian thrust on socialism or planning for the growth of a backward economy. Barely hiding his disapproval, Gandhi wrote, “In my opinion, his planning is a waste of effort. But he cannot be satisfied with anything that is not big.”

When Nehru wrote two letters explaining his aggressive pro-socialist leanings, Gandhi sent him a sharp rejoinder of sorts that read, “The differences between you and me are so vast and radical that there seems to be no meeting ground between us. I cannot conceal from you my grief that I should lose a comrade so valiant, so faithful, so able, and so honest as you have always been; but in serving a cause, comradeships have to be sacrificed” (page 57 in Jawaharlal Nehru’s A Bunch of Old Letters, Asia Publication House).

At a time when the nation is collectively celebrating Amritkal of the country’s independence from the British Raj, the current political class needs to draw some lessons from Gandhi and Nehru in candidly articulating their differences. Tendulkar has quoted Gandhi on Nehru as saying, “He says he does not understand my language, that he speaks a language foreign to me. This may or may not be true. But language is no bar to the union of hearts. And I know this—that when I am gone, he will speak my language” (page 43; Tendulkar D. G.’s Mahatma, Vol. VII, Times of India Press, Bombay).

The writer is a Visiting Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation. A well-known political analyst, he has written several books, including ‘24 Akbar Road’ and ‘Sonia: A Biography’. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment