views

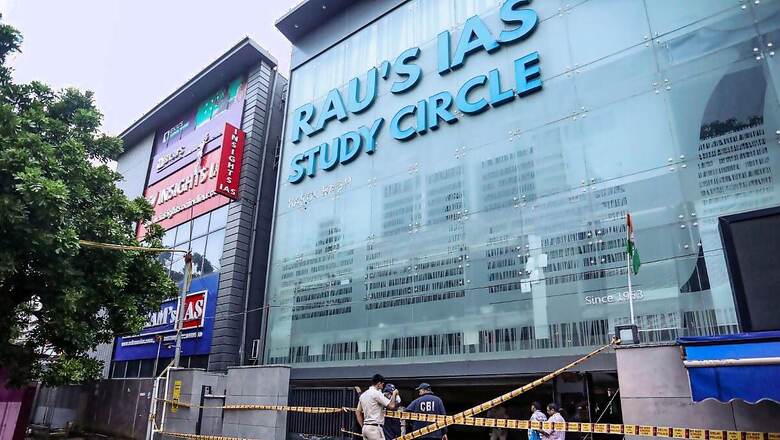

Large-scale illegal construction over sewage lines and coaching centres running student libraries in their basements – these would not have been possible had certain public authorities not kept their eyes wide shut. It only came to everyone’s notice when three young civil service aspirants drowned in stagnant rainwater.

Shift your attention to a bridge or a roof of an international airport that has collapsed shortly after its construction. Is the absence of quality oversight in contracts possible if palms were not greased? Subject to findings of an investigation, it is anyone’s case that reckless corruption rests at the root of all this. News and visuals of such incidents project a decadent image of governance.

Criminals desist from committing an offence only when there is near certainty of getting caught. The cost of committing an offence has to be more than the economic gain out of it. In this context, let us examine if an all-round and robust anti-corruption framework has been put in place to take on the menace effectively.

Indians rightfully deserve to lead a dignified, just and secure life. Corruption erodes trust, weakens democracy, hampers economic development and further exacerbates inequality and poverty. Large-scale pilferage of natural resources or massive financial scams ruining the lives of millions cannot happen in the absence of an unholy nexus of public servants and criminals.

As a result, corruption and transnational organised crime were recognised as two global challenges by the United Nations at the turn of the century. Two important conventions – the UN Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (UNTOC) and UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) — were adopted in close succession.

India ratified the UNCAC in 2011; it urges the signatories to align their domestic laws to criminalise the acts of giving and taking of bribe, abuse of the office by public servants, bribery of foreign public servants, and bribery in the private sector.

To give effect to provisions of the international convention with regard to establishment of the statutory institutions, the office of the Lokpal came into existence through the Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act in January 2014. The Lokpal for the Union has been given power and authority to inquire and prosecute public servants, including the prime minister and Union ministers, on corruption allegations. The high office of the ombudsman, however, is relatively new and yet to become a formidable institution.

2018 amendment to POCA diluted ‘abuse of office by public servant’

The mainstay of the anti-corruption legal framework in India is the Prevention of Corruption Act (POCA), 1988. It has also been amended in July 2018. Through this amendment, the giving of bribe has also been made a distinct offence. However, abuse of office by a public servant, a criminal act as per Article 19 of the UNCAC and also a grave offence defined under Section 13(1)(d) of POCA, has been diluted.

In the amended law, criminal act of abuse of official position has become a variant of the offences of bribing a public servant. Lighter punishment has been prescribed for this offence. At the same time, it has been made mandatory for a police officer to obtain prior approval of the concerned government or the appointing authority before embarking on an inquiry or investigation against a public servant, where the allegation relates to decision taken in discharge of official functions.

Allowing business activities in residential areas, fraudulently issuing fire safety certificates, crafting tender documents to suit a particular bidder, approving below par construction and use of substandard building material, allowing reckless commercial activities in environmentally sensitive zones — all such acts or omissions are instances of misconduct by abuse of official position. Barring the cases directed by the Lokpal or by constitutional courts that don’t require any additional nod, in all other such complaints, getting a prior approval to proceed against a public servant becomes an uphill task and also alerts the suspect.

According to a report in 2023, the CBI — the agency that investigates corruption cases against central government employees, against the bank and central public sector personnel — cannot do so in as many as 10 states. These states have withdrawn general consent to the CBI using Section 6 of another colonial law — the Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act, 1946. As the state anti-corruption and vigilance setups in most states don’t have wherewithal to keep a tab on public servants engaged in affairs of the Centre, the venal elements have a field day in these territories.

Can technology alone fight corruption?

Large-scale leakage of government funds has been checked using technology in public distribution system and through direct bank transfer of subsidies to the individual beneficiaries. Nonetheless, crooks devise newer ways to circumvent the system. For example, in its performance audit report of Ayushman Bharat-PMJAY, submitted to Parliament in 2023, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) noted that in all 7.5 lakh beneficiaries were linked to just a few mobile phone numbers in the beneficiary identification system (BIS) of the scheme. Therefore, the use of technology to fight corruption has its own limitations and stringent punitive measures have an important role to play.

As a prominent global exporter of goods and services, India cannot afford to fall behind by failing to introduce a law criminalising the bribery of foreign public officials as there is significant risk of reputation. Such a law will assure potential investors that Indian companies conduct business in an ethical manner and the enforcement mechanism will detect and prosecute such instances of bribery of foreign public servants. However, a bill placed in Parliament lapsed with dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha. Similarly, to protect the individuals who report the instances of corruption — also a part of the UNCAC commitment — the Whistle Blowers Protection Act was notified on May 12, 2014. But, it was put on hold to amend it to provide safeguards against disclosures affecting integrity and security of the State. The law is also needed to cover the issue of bribery in the private sector.

Global average of corruption perception index (CPI) is 43 out of 100. India scored between 39 and 41 during 2018-2023 as reported by the Transparency International. Corruption-free countries like New Zealand (3) and Singapore (5) maintain high scores. India averaged 33.64 points from 1995 to 2023. These weak scores reflect that, inter alia, the amendments made in POCA have not produced desired results. More effective delivery by the elected representatives on anti-corruption agendas, together with fearless and organised civil society and free press, will definitely create an ecosystem putting India into the league of just and sleaze-free nations. Sooner the better.

(The writer is senior IPS officer Pankaj Kumar Srivastava, who previously held a top position in the CBI, and is presently heading the special task force in Madhya Pradesh. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views)

Comments

0 comment