views

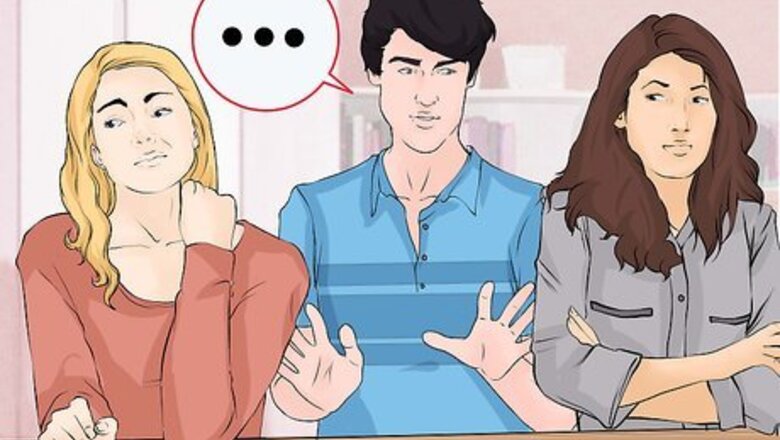

Staying Neutral in Your Friends' Disagreement

Explain to each friend that you are still friends with both of them. Even though they may not like the other, it is not fair to either friend that you end your friendships just because they do not get along. Continue to spend time with both friends just as you would have before. Their conflict should not affect their treatment of you or your treatment of them. Be honest with your friends. Tell them that because you care about and respect both of them, and do not want their conflict to have a negative impact on you, you will remain friends with each of them. Do not show favoritism to either friend. For instance, do not sever ties with one friend at the behest of the other, or due to your own inability to remain neutral in the conflict. Do not spend more time with one than with the other. A good friend will spend equal time with each friend, despite the conflict between them. Consider staying out of the situation entirely. You can be friends with both people without feeling like you need to manage their problem for them.

Emphasize that they must respect your decision. When your friends ask you to take their side, or insist on an explanation as to why you will not support them against the other friend, stay firm. Remind them that you deserve to make your own decisions about your relationships and will not be pressured to do otherwise. Do not give in to threats or intimidation. If Sam says “If you do not side with me and stop spending time with Armin, we will not be friends any longer,” relay your disappointment but stand your ground. Sam, like you, has choices to make about how he acts toward his friends and how much he values your company. If he chooses to give you up as a friend, it’s best to let him do so, as his actions reflect that he doesn't care for you as a friend should. If your friend will not respect your decision and continues to pressure you into denouncing the other friend, or insisting that you agree with them, it might be best to limit contact with that individual. Let them know why, suggesting that “I look forward to spending time with you again when you are willing to accept my neutrality in this matter. I hope you understand that my decision to stay neutral is final.” Choosing healthy, positive relationships means choosing friends who listen to and understand your point of view. If your friend cannot do so, they are failing as a friend. Let them know how you feel by saying “I’m sorry you cannot see my point of view. I feel that my decision is not being respected.” Respect must be given as well as received. Be respectful to your friends who are in conflict. Do not pressure them into spending time together or reconciling before they are ready. Similarly, do not accuse them of being petty or stupid for fighting at all.

Listen to your friends. Let them speak their minds. Allowing them to express their feelings can be cathartic. Knowing that someone has listened to, acknowledged and understood them can help them get over the conflict, or realize they were wrong. Remember, listening to your friend is not the same as validating or agreeing with their point of view. If Sam starts ragging on Armin (or vice versa), insist that you are not taking sides, but you are glad to hear he is thinking about the problem between him and Armin. If Sam asks for your agreement, suggest that “If you feel that way, you should let Armin know. I am your friend as much as his, and I won’t take sides in this conflict.” To start listening, stop talking. You cannot listen when you are constantly interjecting your point of view or telling the speaker they are wrong. Put the speaker at ease with calming body language. Sitting down, putting your hands in your lap, and smiling go a long way toward creating a positive sharing environment. Be patient when listening. Do not interrupt your friend when they speak. Not everyone can quickly and concisely summarize their feelings or point of view. Think about what the speaker is saying. Ask yourself if you agree or disagree and why. Follow up on what your friend said later; perhaps you can help him or her find a new perspective by asking them to clarify what they believe. Responding constructively to what your friend says will show them you care about their point of view.

Stay calm. Never engage in criticism of your own. Even if you get mad at a friend for making acerbic comments, don’t lash out at them. Creating more conflicts will not resolve the dispute between your two friends, and may even make the dispute worse. If you feel yourself becoming frustrated with your friend, excuse yourself. Say something like “I am frustrated by the way you are speaking. Let’s continue this conversation later.” Try deep breathing techniques; slowly repeating a mantra or a relaxing phrase (“I am cerulean blue; I am a cool breeze”); or envision a peaceful scene such as a pine forest or snow-capped mountaintop. Don’t act defensively if your friend starts blaming you or name-calling for your decision to remain friends with the other individual. Stay cool. Do not become angry just because he or she is angry. The problem is their attitude and perception, not you. Do not take their insults or bad attitude personally. Use humor to defuse a tense situation. If you or your friend are getting really worked up over the conflict between your two friends, try to make a joke of the situation. Do not be sarcastic or caustic with your humor. Rather, employ some self-deprecation and a congenial tone to reevaluate the situation you and your two friends are in.

Refuse to act as a go-between. If one friend asks you to pass a message on to the other, tell them they should bring it to the other friend directly. Instead of acting as a go-between, instruct your friend(s) to give you more information about what they want to say, and offer to help them find a great way to say it. Acting as the messenger for one or another of the warring parties may bias the other against you. Sam might, for instance, suppose that you were half-hearted or insincere in your extension of the peace offering or apology to Armin if Armin does not accept the offer of reconciliation. Emphasize to both friends that reconciliation can only occur when both are willing to speak to each other directly and honestly. Apologizing, forgiving, and trust-building can only be accomplished via direct communication between the two individuals involved in the conflict. Once these are achieved, the conflict often takes on a new dimension as the parties work towards a resolution.

Unless one friend is clearly wrong, do not take sides. If this is just a personality clash, you can't make it better by taking sides. If one of them asks you to, or tries to make you feel guilty enough to do so, simply refuse. Say, "Hey, this is between you guys. I'm Switzerland." Do not intervene in the substance of the dispute. When the subject is raised, try to change the direction of the conversation to something different. If you friend insists on speaking about it, let him or her do so, then remind them that you cannot support or takes sides in their conflict. Typically, neutrality indicates that you are disinterested in the results of the conflict or the parties involved. However, as a friend of both parties, you may rightly have an interest in their conflict and hope they will resolve it amicably. There is no problem with this desire, since it is what good friends wish for one another.

Cultivate mindfulness to help you remain neutral. Cultivating mindfulness can make you more aware of your own thoughts and biases. Mindfulness is a quality which instills peace of mind and a positive attitude in those who possess it, especially when they're making tough decisions or dealing with stressful situations. If you are mindful, you will be more aware of your feelings about the conflict between your two friends who hate each other. This can help you remain objective and neutral. You can gain mindfulness through yoga, tai chi, or mediation. Mindfulness requires three skills: Awareness. This means being alive to the moment and the things going on around you. When you are talking with your friends, enjoy their company. Do not dwell on the conflict between them since it is not occurring at that moment. Think about how much you enjoy being with them. Responsibility. Responsibility requires a kind and generous attitude toward yourself and others. In a conflict between two friends, this means you should do what’s best for both parties involved. Empathize with each, speak and act without preference or judgment, and remain neutral. Effort. This means acting on your awareness and responsibility. When two friends are fighting and you wish to remain neutral, making a big effort to do so will be difficult. You can continue to be neutral and build mindfulness by acknowledging that you are in a difficult position but must stay the course for the good of yourself and your friends. Neutrality can seem like an impossibility. Everyone has biases, both conscious and unconscious. Being more aware of yours will help you overcome these biases.

Taking Sides if One of Your Friends is Right

Ask yourself if your wrong friend can accept the truth. Some people will not be willing to hear the truth no matter what. Think about your friend’s personality in order to gauge whether informing them of your true feelings is a good idea. Are they willing to accept criticism? Do they readily admit to being wrong when confronted with compelling evidence? Do they take responsibility for their actions when wrong? If so, sharing the truth with your friend is a good idea and will likely make a positive change. If, conversely, your friend is frequently defensive and shifts blame onto others when confronted with evidence of his or her shortcomings, your honest efforts at helping them see that they were in error will be wasted. In the case of a defensive friend, try to broach the subject in a variety of ways. If they don’t understand that what they did was wrong the first time you explain it, maybe they need to hear it a different way. Perhaps the first time you broach the subject, you’re indirect: “Do you think that what you said to Sam was kind?” If they blow you off, make a stronger declaration next time: “You were very rude to Sam. He deserves an apology.”

Be clear in your disapproval. Do not try to qualify your point of view by agreeing half-heartedly to your friend’s insistence that the other person is wrong. Do not begin with a statement of praise before delivering the reality-check that your friend is in the wrong. Finally, do not employ phrases like “With all due respect” or “No offense, but...” Be direct and honest in your evaluation of your friend and explain why he or she is wrong. For example, if Sam called Armin stupid directly or indirectly, and Armin (rightfully) refuses to hang out Sam, you should tell Sam “It was unkind and wrong of you to call Armin stupid. You owe him/her an apology . That’s the best way to put this conflict behind you.” Do not cover up your feelings of disappointment or frustration. When you fail to express yourself to the person you have negative feelings toward, the feelings remain trapped, which leads to further frustration. You may experience a building sense of resentment, apathy, detachment, and disdain, either generally or towards the friend who you didn’t confess your feelings towards. To avoid the buildup of negative feelings, let the friend whose behavior you disapprove of know immediately. You may worry that your friend will be displeased when you admit you do not support their previous action or offense against your other friend. This fear is unjustified, since openness and honesty between friends can strengthen the friendship.

Focus on the behavior, not the character. Remind your friend that while they should not have spoken to, treated, or badmouthed your other friend in the way they did, you know they are still a good person. Emphasize to your wrong friend that they made a mistake, and that they can and should make amends. Don’t make assumptions or generalizations about your friend’s personality. For instance, do not say “You don’t know how to deal with people.” Instead, say “You spoke rudely to Sam, and that was wrong.” Emphasize that he or she can change. Encourage your friend to stay aware of how he or she might cause offense and avoid doing so in the future. If your friend has difficulty changing a particular antagonistic or confrontational behavior, advise them to consult a therapist. Cognitive behavioral therapy is especially useful in transforming negative behaviors. This type of therapy encourages individuals to actively consider their evaluation and processing of certain situations in order to help them adjust their emotions and behavior. Ask your friend how you can help. Suggest that in the future, you point out similar behaviors in a nonjudgmental way.

Be kind. Offer criticism in a gentle way. Do not call your friend names or raise your voice when explaining why you feel they are in the wrong. Conversely, do not shut them out or give them the silent treatment. Communicating your point of view in a healthy way will prevent the situation from escalating, and your friend might be more understanding of the person they were originally in conflict with when they hear your perspective. Remember that the conflict between your two friends is not the end of the world. It is only one part of your whole friendship with each of them. Understand that both you and your friend(s) may have valid points. Sometimes agreeing to disagree is the best option. Tell your friend(s) “I would have handled the situation differently, but I see where you are coming from.” When discussing sensitive issues with your friend like the conflict between him/her and another individual, be discrete. Do not bring it up in large social situations where others who are unaware of the conflict might learn of it or weigh in without understanding all the facts. Friends should always be sensitive to each others feelings. Do not employ shame, blame, or a judgmental tone when speaking to your friend about the conflict.

Helping Your Friends Find a Resolution

Discover the sources of the conflict. Why do your friends dislike one another? There might be one reason or many. Your friends may not get along because one or the other of them acted badly. Whatever the cause(s), identifying them is the first step toward resolution. Ask each friend why the conflict began. Let's say you have two friends, Armin and Sam. Ask Sam why he dislikes Armin. Maybe Sam doesn't really have a reason, but just feels vaguely uncomfortable or uneasy around Armin. Go to Armin next. Repeat your question. From Armin, you learn that at some point, Sam said something that hurt Armin's feelings, or made him feel insulted. Maybe they had an argument over something. Whatever the case may be, armed with a basic understanding of the problem, you can try to work with them to resolve it. Sometimes your friends may not tell you why the conflict began. Perhaps they both said or did something wrong and are afraid, ashamed, or embarrassed to share it with you. In this case, with the permission of your friends, you might try to enlist the help of a third party trained in conflict management to investigate why the conflict between your friends began. Many conflicts are caused by simple misunderstandings. Perhaps Sam failed to remember Armin’s birthday; perhaps he thought Armin badmouthed him behind his back. Helping your friends identify the roots of their conflict can empower them to move past it.

Explain how their conflict hurts you. When your friends fight, you’re put in a difficult, and often stressful, position. After all, you must constantly watch what you say, choose how to balance your time, and endure hearing negative comments about one from the mouth of the other. If your friends understand this, they will be more willing to bury the hatchet. Not talking about negative emotions like frustration, emotional hurt, or disappointment will only enlarge them. Talking to your friends about your feelings on their conflict is important not only for its potential to speed their swift resolution but for its ability to give you good mental health. If your friend does not care about your feelings, and is unable to concern themselves with your feelings and point of view, don’t bother sharing them with that friend. You can detect this behaviour by listening to their response when you share your own perspective. For instance, you may explain to Sam that you feel stressed by his fight with Armin. If Sam replies that he, too feels stressed and does not appear to be acknowledging the psychic pain you’re experiencing, Sam is too self-centred. Limit spending your valuable time with such a person. Do not blame or attack when expressing how you feel. Use “I” statements rather than “you” statements. In other words, instead of saying “You’re very inconsiderate and it stresses me out,” say “I feel very stressed by this whole situation.” Where the former sentence is accusatory and will inspire the listener to defend him or herself, the latter sentence is explanatory and personal, and engages the listener in dialogue. If you have a hard time giving voice to what you feel, write it out before addressing your friends. This will allow you to explain yourself more fully without dealing the the pressure that sometimes comes from a face-to-face meeting.

Mediate the dispute. When you mediate a situation, you act as a referee, trying to get the two of them to bring their problems and concerns out in the open with the goal of reconciliation. It can be a challenge, but is well worth it when two people who hate each other are finally able to set aside their anger and hate. Bring both people to a neutral location. Do not meet in either of their homes. The one on "home turf" may feel they are the boss, and the one who is not will feel ill at ease. Private rooms in a library or school are good options. Thank them both for meeting each other with the intent to settle their differences. Let them know that they are both important to you and you want to see them patch things up. Lay the ground rules: interrupting each other, name-calling, yelling, and other emotional outbursts are forbidden. Insist each party acts with mutual respect and remains open-minded. Without these basic guidelines in place, the process could easily deteriorate into a shouting contest. Encourage each party to speak their minds. Ensure the other listens carefully to the opposing perspective. If either side feels they are not being heard or the mediation effort is futile, they will not invest themselves in the process and it will be fruitless for all three of you. Illustrate to them how similar they are. Find the common ground between them -- especially the fact that they are both friends of yours. If it starts to turn ugly, put a stop to it. "All right, all right,” you might say. “It's pretty plain to see that you guys are not going to be able to work this out today. I plan to remain friends with both of you, so I hope that you will try to be civil to one another in the future." If you do not believe you are unbiased enough to settle the dispute, identify and seek assistance from someone with the diplomatic skills who may be able to. A good conflict mediator will be neutral (evaluate the situation objectively); impartial (act without a stake in the outcome); and fair (approach each side in a balanced manner). Enlisting help of am unbiased third party who does not know either friend is a good idea if you do not want to mediate yourself.

Be patient. Don't expect them to patch up everything overnight. If the first mediation is unsuccessful, don’t give up. Use the experience to plan another one. Talk to each individual about their thoughts after the first mediation session. If you detect a softening of attitude or tone in both or either party, suggest a follow-up mediation in another week or so. Continue to offer your support and friendship to both, and if one or another of your friends broaches the subject, express your continued hope that a positive resolution can be found. Do not try to pressure either party into accepting a resolution they are unhappy with. This will either break down the resolution process entirely or cause one (or both) friends to feel resentful at having been “forced” into a bad deal.

Come to a resolution. Brainstorm some possible resolutions with the interested parties. Each individual should have some input. Look for win-win solutions where both individuals walk away happy. For instance, if the problem is that Sam felt snubbed because Armin didn’t invite him to his party, suggest that Armin invite Sam to his next party as the guest of honor. With all the possibilities in front of you, consider the pros and cons of each. Print a spreadsheet outlining each possibility with the pros and cons and distribute one to each friend. Keep both friends focused on finding an outcome. Continue to push them toward compromise and give each individual equal time to speak. Paraphrase and ask questions of each friend’s statements at regular intervals to ensure you are understanding them correctly. Give each a chance to modify what they have to say if any confusion arises. A lasting resolution must address both the substantive and emotional issues. Substantive issues are objective facts which are not debatable. For instance, Armin crashed Sam’s car into a wall -- that’s a substantive issue and might be the central trigger which led to the conflict between them. Sam felt betrayed and let down by Armin because he’d loaned Armin the car in good faith with the pledge that nothing would happen to it. Sam’s feelings of betrayal and disappointment are the emotional issues. A resolution for a substantive issue, using the above example, might be Armin paying for the repairs to the damaged car. A resolution to the emotional issues might be Armin admitting his wrongdoing and apologizing to Sam, and Sam accepting that apology. If one or the other of your friends won’t accept a resolution, return to the process of asking questions, listening to their reasoning, and understanding what their desires are. Listen to what they have to say and continue working with them toward a resolution.

Comments

0 comment