views

Interacting with Patients

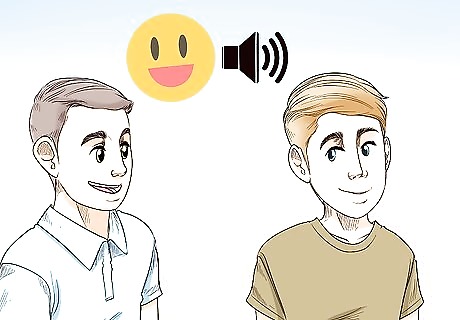

Use a friendly, but professional tone. The patient should recognize that you have authority, but not feel as though you are talking down to them. A friendly tone helps in accomplishing this, as it conveys to the patient that you care about them. Keeping it professional shows the patient that you are confident about their treatment and feel in control of the setting.

Keep your focus on the patient's treatment plan, not your opinions. Patients may say and do things that you think are inappropriate or upsetting, but it’s important that you not convey this to the patient. Rather than informing them of your opinions, follow their treatment plan and help them get back on the road to recovery, whether you agree with their actions or not. At times, this may mean consciously addressing your biases. For example, you may find self-harming behavior to be upsetting. However, chiding a patient or showing disgust can set them back. Instead, treat their wounds and help them engage in their treatment protocols.

Treat each of your patients in the same manner. Some of your patients will be harder to work with than others. For example, you may have a patient that is more aggressive or who shows disdain for you. It’s important to treat this patient the same as any other patient, including how you address and behave towards them. Treating them equally is not only the right thing to do, it can also aid in their treatment process. Eventually, it may make them cooperate better, as well.

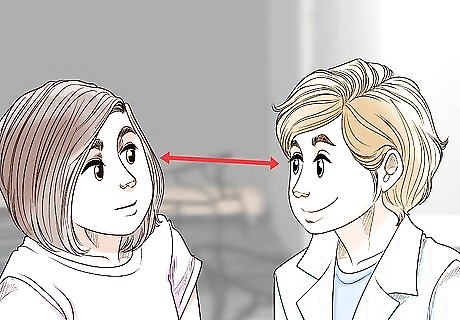

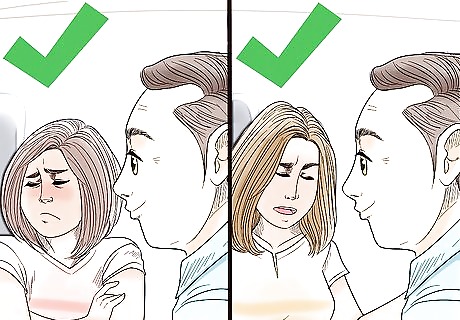

Make eye contact when speaking to patients. Keep your eye contact natural, however, rather than forced. This shows the patient that you are open, honest, and view them as an equal. Do not stare down at patients, as this may come across as demeaning to them.

Use open body language to avoid triggering negative emotions. Patients will notice if your body language appears hostile or angry, which could be a trigger to some patients. You can avoid this by adjusting your body language. Straighten your back and maintain good posture. Let your arms hang at your side. When holding something, try not to block your body with it. Don’t cross your arms. Keep your facial expression neutral or, preferably, give a friendly smile.

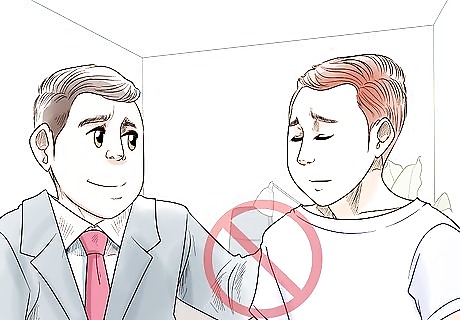

Do not invade a patient’s personal space unless it's necessary. Unless you're in an emergency situation, earn a patient's trust before you try to get too close to them or enter their private space. Although there may be times when you or other staff must cross personal boundaries for the sake of the patient or others in your care, do your best to respect their space. You could say, “I’m noticing that you look upset. Can I sit with you and talk?”

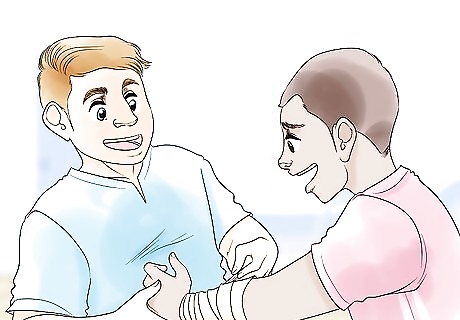

Avoid touching patients, unless it’s necessary. Some patients can become anxious or upset when they’re touched. It may even be a symptom of their illness. Don’t touch a patient unless you have permission or it’s required for their treatment.

Meeting Patient Needs

Listen to the patient’s concerns. Patients are less likely to act out if they feel you are truly listening. In some cases, the patient’s concerns may sound irrational or be a reflection of their symptoms. For example, they may be having a delusion. Even if this is the case, listen to what they have to say. Show the patient that you are listening by nodding and giving affirmative responses. Summarize what they are saying to you, so that they know you understand them correctly.

Respond to the patient with empathy. It’s important that the patient knows you care about how they feel. Not only will your empathy help them work through the situation, it also helps you keep them calm. Try to validate the person's feelings. Show the person that even though you might not be experiencing the same exact thing they are, you can understand why it would be causing them distress, and let them know that feeling is okay. That can make them more likely to put down their defenses and tell you more about what's going on. For instance, you could say, “That sounds really stressful,” or “I can understand why you’re so upset.”

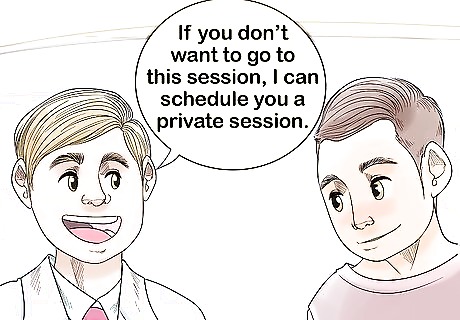

Give the patient options. Sometimes a patient will resist complying with treatment or the rules of the facility. When this happens, acknowledging their feelings and giving them options can help guide them toward your desired outcome. Options allow the patient to feel that they have some control in the situation. When you're creating a treatment plan, take the patient's desires into account when it's appropriate. For instance, your patient might prefer therapy over medication, they might only want medication, or they might like to try a combination of the two. You could say, “It sounds like you don’t want to go to group today. It’s important for your treatment plan that you participate. If you don’t want to go to this session, you can go to the afternoon session or I can schedule you a private session to discuss your treatment plan.”

Adjust your treatment to fit the patient’s personality. It’s easier to treat the patient if you understand their personality and adapt your treatment to it. That is because how each patient accepts and approaches treatment differs. There are four different personality traits that can affect how the person approaches treatment: Dependent: A person that feels dependent on others will expect help and possibly even a full recovery. They will often be compliant, but may not take action on their own. Histrionic: A person who has a histrionic personality may be more dramatic in how they present themselves. They may exaggerate their symptoms to seek attention. Antisocial: These patients may resist treatment and display disdain for their medical team. Paranoid: Paranoid patients may resist treatment because they don’t trust the doctor or doubt what they’re being told.

Never lie to the patient to gain compliance. Lying may appear like a good option when a patient refuses to comply, but it will make things worse in the long-run. Examples include hiding medication in the patient’s food, promising not to restrain them and then doing it, or promising a reward but not delivering. This will cause the patient to distrust you and resist you more strongly in the future. When a patient feels like they can trust their mental health providers, they're more likely to have a successful outcome from treatment. An exception to this is that if the patient’s treatment plan suggests following along with a delusion they’re having, you should lie when appropriate to avoid questioning the delusion.

Treat psychiatric patients as well as you would any other patient. Unfortunately, biases exist against psychiatric patients, especially those who harm themselves. This can prevent the patients from getting the care they need to recover from their conditions. In some cases, patients are discharged earlier than they should be because of negative perceptions on the part of staff.

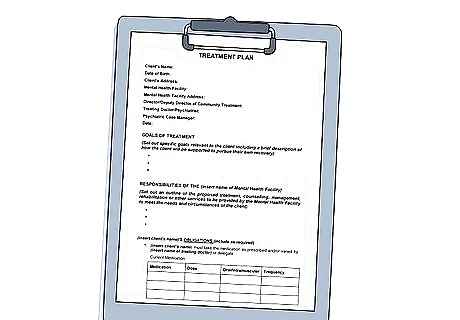

Keep detailed documentation. Good records are essential to providing excellent care. Each care giver should document the patient’s diagnosis, treatment, and related information, such as recurrence of symptoms. This ensures that the patient’s treatment team knows their full medical history, so that tailored care can be provided. Additionally, good documentation protects you and other staff in the event of a malpractice claim.

Involve the patient’s relatives in their treatment when possible. In some cases, you may not be able to involve relatives because of HIPPA laws. However, whenever possible, invite relatives to participate in the patient’s treatment. This will improve the patient’s outcome, especially after they go home. Invite them to a special family therapy session. If allowed, show them the patient’s treatment plan.

Dealing with Aggressive Behavior

Check their treatment plan. If it’s available, the patient’s treatment plan should outline the best practices for de-escalating their condition. Everyone is different, and there are many reasons why a patient may become aggressive. It’s best to consult their plan before taking action, if it’s possible. In an emergency situation, such as when the patient or someone else is at risk, you may not have time to consult their treatment plan.

Move the patient to a calm, secluded environment. This could be their personal room or a special space in the facility for this purpose. This will give them time to calm down on their own. This works better for patients who are overwhelmed.

Remove or hide any objects that could be used to harm. Do your best to protect yourself, other patients, and the aggressive person. Remove the most dangerous items first, and don’t leave anything that they can throw or swing.

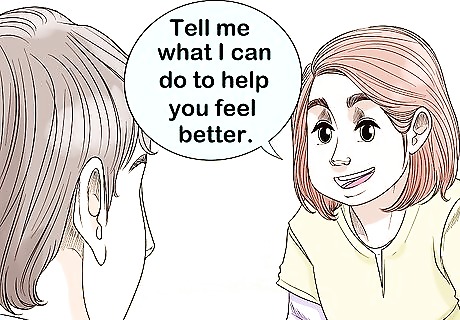

Acknowledge their feelings to open a dialogue. Don’t argue with the person or try to explain why their feelings aren’t valid. This will just upset them more, making the situation worse. Say, “I can tell you’re upset. Tell me what I can do to help you feel better.” Don’t say, “There’s no reason to be angry.”

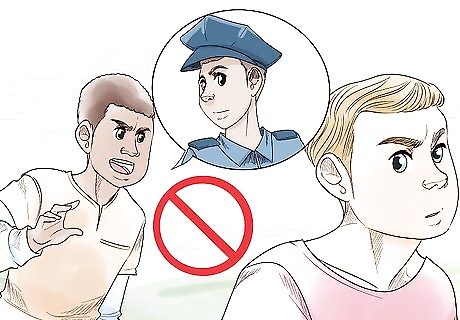

Do not make threats. It’s tempting to tell the person that things will get worse for them if they don’t calm down, but that’s often ineffective. In many cases, it makes the patient become more aggressive. Threats can range from committing the patient, extending treatment, calling the police, or other undesirable “punishments.” Instead, offer assistance. Avoid statements like “If you don’t stop yelling, I’m going to call the police” or “You’re about to add two more weeks to your stay here.” Instead, you could say, “I can tell you’re angry, and I want to help you resolve those feelings. I’m here to help you.”

Administer medication to help calm the individual, if necessary. Sometimes the patient will not calm down without an intervention. In this case, you may have to medicate them. It’s best to try to administer the medicine without restraining them. Most often, these medications will consist of antipsychotics or benzodiazepines.

Use physical restraint only when needed. This is usually reserved for a hospital setting with trained individuals. Restraining a person is often a last resort, allowing medical staff to administer drugs that will calm the patient. It’s dangerous to restrain a person who is acting out, so be careful.

Coping with a Family Member’s Mental Illness

Learn about their illness. Read about the illness online or in books. When appropriate, talk to their doctor to understand your family member’s unique experience. It’s also a good idea to talk to them about it, if they’re comfortable sharing. You can find resources online, in your local library, or in your local bookstore.

Support their recovery efforts. Let them know that you’re there for them and want to them to take the time to get better. In some cases, they may be managing or dealing with their symptoms throughout their entire life, with frequent relapses. Let them know that you will be there for them. Talk to their doctor and/or social worker, when appropriate. Tell your loved one that you’d like to help with their treatment plan, if they feel comfortable. You could say, “I love you and want you to feel better. If you feel comfortable, I’m happy to read over your treatment plan and help in any way I can.”

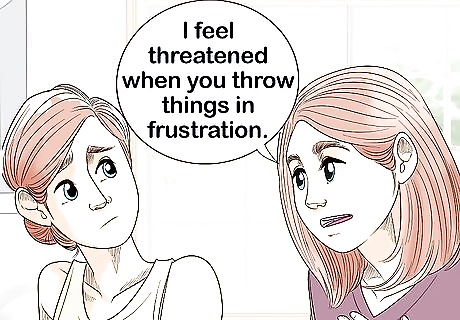

Speak in “I” statements when discussing issues in the relationship. It will likely be necessary for you to confront issues at times. When you must address a problem, always frame it using “I” rather than “you” statements. This makes your comments about you, not them. For example, “I feel threatened when you throw things in frustration. I would feel safer if you worked with your therapist to reduce those urges.” Don’t say, “You always throw stuff and scare me! You need to stop!”

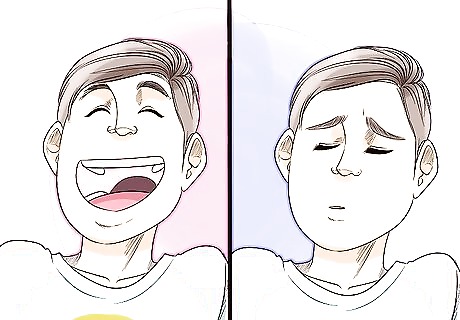

Manage your expectations for the person’s recovery. Many patients spend their whole lives managing their illness. Even with treatment, they may still experience symptoms. Don’t push them to “act normal” or take on responsibilities. This could cause conflict in the relationship, lead to a setback or worse, both.

Join a support group. Sharing your experiences with people in a similar situation can help you cope better. Not only will they listen to you, they may also have helpful advice. You may also be able to learn more about your loved one's condition. Ask the doctor or treatment facility for a recommendation. Call local mental health centers to look for groups, or search online. For example, you may be able to join a local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). If possible, find an open support group that you and your loved one can attend together.

Comments

0 comment