views

Previewing the Interrogatories

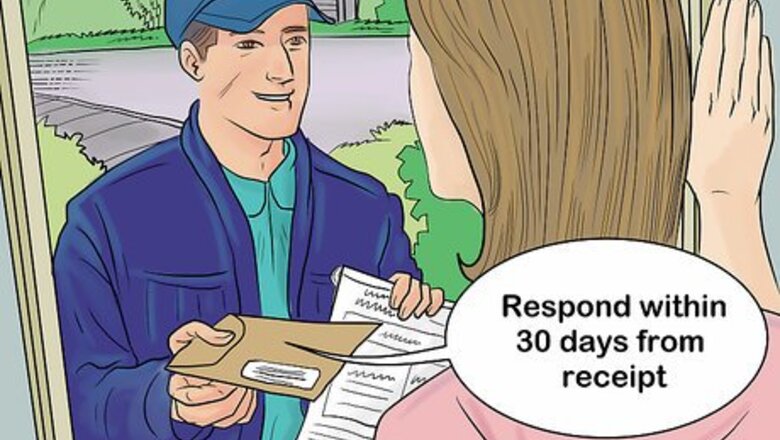

Begin working on your responses as soon as you receive the interrogatories. In most courts, you must submit your responses to interrogatories within 30 days from the date they are delivered to you or your attorney. Recall that this time includes meeting with your attorney (if you have one), collecting relevant documents, reviewing and preparing your answers, typing the response, reviewing the responses with your attorney, copying the responses, and delivering them to the other party. It’s not a lot of time, so get started right away.

Discuss the interrogatories with your attorney, if you have one. If you have an attorney, then most likely he received the interrogatories and has sent them to you with instructions to answer them. He has probably already identified the ones that deserve legal objections, and he will handle that part of it. You should sit with your attorney, read through the questions together, and briefly discuss what your answers will be for each one. Your attorney can guide you to make sure that your answers are consistent and appropriate for your overall case.

Review all information before answering questions. Read each question before you answer any of them. Read through all of the information and evidence made available to you, as well. Reviewing related documents will allow you to form answers that are complete and accurate. Make sure that you understand each question before you answer it. If you are uncertain about a particular question, consult with your attorney.

Gather any information you may need to help you answer. Before you start writing down answers to the interrogatories, it may help you to pull together any paperwork, contracts, receipts, witness statements, or whatever other information you may have that is relevant to the case. That way, when you get to certain questions that ask for names, dates, or other specific information, you can more easily look it up. You are not required to conduct any special research in order to answer interrogatories, but you are expected to look up some information that you would reasonably have available. For example, suppose you are involved in a car accident case because your brakes didn’t work, and the other party asks you, “What was the number of accidents caused by brake failure in the U.S. in the past five years?” You should object, because you cannot be expected to look up this information. On the other hand, suppose you are asked, “How many times have you had your brakes serviced since you purchased the car?” This is a reasonable interrogatory. Even if it means that you may have to estimate or look through car repair receipts, you should answer it. In the end, if you truly don’t know, you could estimate or answer that you don’t know.

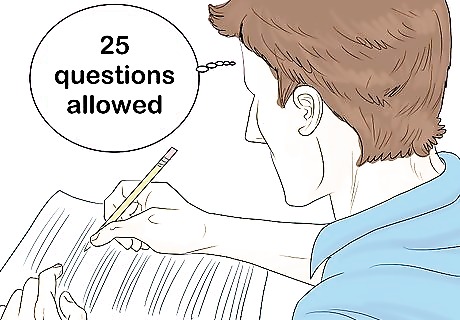

Count the number of questions. Look through the interrogatories that you received and simply count to make sure that the opposing party has not exceeded the allowable limit. When you are counting, if a question is presented in multiple parts, you can count it as multiple questions. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule Number 33, allows 25 questions, “including all discrete subparts.” This means that you can break a multiple part question into its parts and count each part. The Federal Rules will apply if your case is in Federal Court. State rules apply in state courts, and may allow more or fewer than the Federal Rules. In most states, the Rules of Civil Procedure will follow the same numbering structure as the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. If Federal Rule Number 33 covers interrogatories, then in your state court’s rules it will probably also be Rule Number 33. For example, a question that says, “Identify each person who was present at the accident scene and describe what each person did immediately following the accident,” is really two questions: (1) Identify each person and (2) Describe what each person did following the accident. Count this interrogatory as two questions.

Identifying Objectionable Questions

Object when you need to. Interrogatories are a chance for either party to a lawsuit to get information from the other party by asking questions. However, there are some limits to what can be done with interrogatories, and if your opponent goes too far, don’t be afraid to raise an objection. If you are working with an attorney, he will probably point out the objections first. But if you have concerns, ask him about it.

Dispute questions that are impermissibly compound. Each interrogatory is supposed to ask only one question. If the interrogatory raises multiple questions in one, this may be grounds to object. An example of an impermissibly compound objection would be, "Name each person who was present at the accident, and for each person describe what he or she saw, give that person's address and work experience, and provide a history of the repairs that you have had done on the car."

Contest questions that are vague, ambiguous or unintelligible. If possible, interpret each question in a way that can be answered. But if, no matter how you try, you cannot make sense of a question or find a way to give a specific answer, then object. For example, if the question asks, “When did he do it?” without any more specification, you need to object because you cannot be expect to know who “he” is or what “it” is.

Challenge questions that assume facts that are not proven. For example, if a question asks, "What did the passenger in your car say when you ran through the red light?" is objectionable if it is not clear that you did run through the light.

Object to questions that are not reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of relevant, admissible evidence. Interrogatories must ask questions that are, at the very least, relevant to the case. Any question that asks for too much detail that goes beyond the scope of the lawsuit is objectionable. For example, if you are in a contract dispute case regarding a specific purchase, and you are given an interrogatory that says, “Please identify your annual income for the past three years and provide copies of tax returns,” this would be objectionable. Your income probably has nothing to do with the contract in question.

Ask your attorney about any objections that you consider. If you are represented by an attorney, then he or she, in fact, will be the one who is technically making the objections. Your role is to provide answers to questions. The attorney's role is to make legal objections.

Answering the Interrogatories

Complete “list” questions as thoroughly as possible. “List” questions are those questions that will directly ask you to list specific pieces of related information. You must provide each known piece of information requested. An example of a standard list question might read, "List the names, business addresses, dates of employment, and rates of pay regarding all employers for whom you have worked over the past five years." Leaving information off your list can prevent various witnesses and evidence from being introduced. Moreover, if the information you omit is revealed during the trial, the validity of your testimony could be called into question. When asked for dates, be precise if possible, but do not guess. If you can only remember the month and year, then say so. If you can only remember the year, then say that. However, if you can readily find the answer for a precise date, you should do so. When necessary, go through your records to answer list questions as thoroughly as possible. If you know that there is information you are unable to recall and do not have records for, mention this fact after completing the rest of the list.

Answer “yes-or-no” questions simply. Yes-or-no questions are fairly straightforward. The first part of the question will ask a closed-ended question that you'll need to answer with a "yes" or "no." The second part of the question will ask you to provide further detail. For example, a yes-or-no question might ask something like, "Were you receiving treatment for any physical disability or sickness during the time of the complaint? If so, state the nature of the condition, the type of treatment, the date you began treatment, and the physician in charge of your treatment." If your answer is "no," all you need to do is write "no." Do not answer the second part of the question. If your answer is "yes," you will need to answer the second part of the question with information that is both thorough and accurate.

Be concise when answering narrative questions. Narrative questions are open-ended and ask you to describe events related to the case. Provide accurate, complete information, but do not answer more than is necessary. If adding some particular details will help your case, then include them. But do not feel compelled to include details that may not help your case. An example of a narrative question could be something like, "Describe in detail the actions you performed leading up to the accident mentioned in the complaint, including the known results of each action." Provide brief answers that address all of the points raised in the question while mentioning little else. Do not include irrelevant details, and make sure that your answers do not shift the blame for an incident to yourself. If you are asked to answer what you could have done to avoid an accident or incident, don't guess or speculate on what actions you may have taken. It is better to write, "There was nothing I could do to prevent it” or even simply “I don’t know what else could have been done.” If describing injuries, mention any and all injuries linked to the incident, including those you believe to be minor. Remember that any facts you leave out of your interrogatory answers might not later be admitted in court.

Leave open the possibility for future amendments to questions about trial preparation. Some questions may ask about your plan for the trial, such as, “List all expert witnesses you intend to call at trial.” At the time that you are dealing with the interrogatories, you may not have yet identified any expert witnesses. So you will answer, “No expert witnesses are known at this time. I reserve the right to amend this answer if and when any are identified.” Then, if you do find an expert witness that you will use at trial, make sure you send the opposing party a letter that add this name to your answer. In the final preparation stage for trial, there will be a time for each party to provide a full list of witnesses and exhibits that are going to be used at the trial. Your list of witnesses or exhibits at this time should match whatever information you previously provided in responses to interrogatories. If they don’t match, your opponent could raise an objection and delay the trial or prevent your witness from testifying.

Preparing Your Final Response

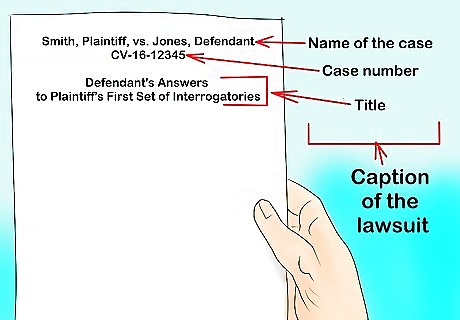

Use the proper heading for your interrogatory responses. Interrogatory responses should be headed with the “caption” of your lawsuit. This will include the name of the court centered at the top of the page, the name of the case (e.g., “Smith, Plaintiff, vs. Jones, Defendant”), and the case number, something like CV-16-12345 (the case number will have been assigned by the court clerk when the case was filed and needs to appear on all documents). Then you will title the paper, “Defendant’s Answers to Plaintiff’s First Set of Interrogatories” (assuming that you are the defendant and this was the first set). Either party may serve interrogatories on any other party in the case. It is permissible to send more than one set of interrogatories, as long as the total number of questions does not exceed the number allowed by the rules of civil procedure. So, for instance, a party could send the “First Set of Interrogatories” that contains ten initial questions, and then after reviewing the answers to those questions, submit a “Second Set of Interrogatories” with fifteen additional, more specific questions. If you have an attorney representing you, then you probably will not need to worry about this step. You will just provide the answers, and the attorney or his or her staff will make sure that the page is set up correctly.

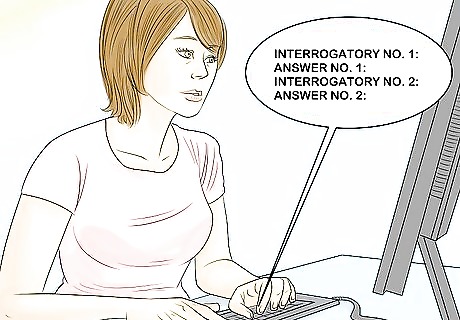

Format your answers properly. As a general rule, you should write your answers on a separate document, not respond directly on the page you received from the other party. This document can be a computer file or a typed, printed response. Legible handwritten replies may also be sent but are not preferred. Generally, for legibility, your responses should be double-spaced and printed on one side of the page only. If possible, without becoming overly burdensome, you should retype each interrogatory and follow the question with your answer. In most courts, repeating the question is not required, but it is helpful and generally expected, to make reviewing the answers easier. Your response will look something like this: INTERROGATORY NO. 1: ANSWER NO. 1: INTERROGATORY NO. 2: ANSWER NO. 2:

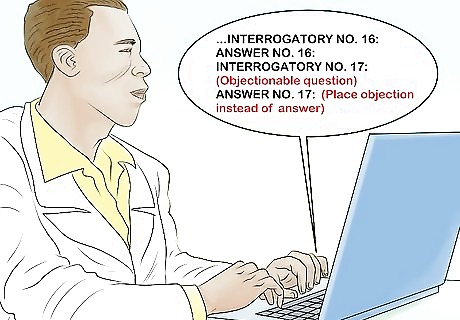

State any objections in the space where the answer would go. You do not list objections separately. If you have any objections to particular interrogatories, you will present them instead of an answer. If you can answer part of a question but part of it is objectionable, then answer what you can and object to the rest. For example, the following might be what your response would look like if you were involved in a case about a car accident: INTERROGATORY NO. 17: Identify the make and model of the car you were driving at the time of the accident, and provide the number of similar accidents involving that make and model car in the U.S. for the past year. ANSWER NO. 17: I was driving a 2013 Honda Accord. I object to the remainder of the question as it requests information that is overly broad, irrelevant to this case, and calls for additional factual research.

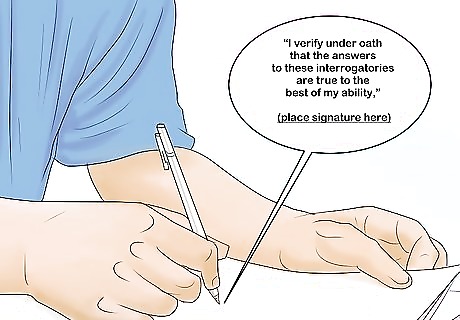

”Verify” your answers by signing the final page. In legal terms, a “verified” answer is one that you have signed at the end. You need to include a statement at the end of your interrogatory answers that says, “I verify under oath that the answers to these interrogatories are true to the best of my ability,” and then sign it. If you are represented by an attorney, and the attorney provided language for any objections, then the attorney will also sign in support of those objections. Some attorneys disagree on whether you need to include the words “under oath” in your statement. As long as your answers really are true, you should probably include the “under oath” language. If your answers are intentionally false (i.e., you are lying), and you sign the statement “under oath,” then you could be charged with the crime of perjury. If you tell the truth, to the best of your ability, you have nothing to worry about. The rule on this may differ from state to state as well. In some states, your answers may need to be signed in front of a notary as well.

Make copies. Even if you save the document on your computer, make a copy of your signed interrogatory answers before sending them out. You will need to send a copy to every party in the case. The original must be sent directly to the requesting attorney or self-represented party who sent the interrogatories. In some cases, there may be more than one plaintiff, or more than one defendant. You need to send a copy of your responses to everyone involved in the case.

Complete and return the interrogatory answers within 30 days. Under most circumstances and in most states, you must answer and return the responses to interrogatories within 30 days of receiving them. The exact deadline can vary if the judge presiding over the case decides to set a different time limit. In such instances, the new deadline should be clearly stated when the interrogatory is delivered to you. If you have a valid reason for being unable to meet the deadline, speak to your attorney about the possibility of requesting an extension. If you are not represented by an attorney, then call the other party (or his or her attorney) directly and discuss an extension. Most attorneys will be reasonable about discovery, if you act reasonably as well. If you fail to complete and return the interrogatory by the deadline, the court could sanction you or take other legal action against you. If you are just late, then at first, the court may just order you to answer. But if you continue to delay or refuse to answer, the court could order a financial fine against you, could limit your ability to present certain evidence or witnesses, or take some other action that the judge thinks is appropriate.

Comments

0 comment