views

X

Research source

Taking an Apical Pulse

Start by asking the patient to take off their shirt. To take the apical pulse, you will need to access the bare chest.

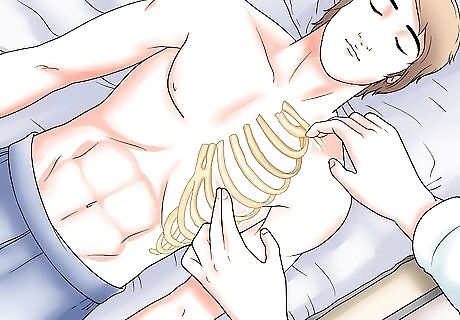

Feel the first rib by finding the clavicle. Feel for the clavicle. The clavicle is also called the collarbone. It can be felt at the top of the rib cage. Directly below the clavicle, you should feel the first rib. The space between two ribs is called the intercostal space. Feel for the first intercostal space—the space between the first and second ribs.

Count the ribs as your work your way down. From the first intercostal space, move your fingers down to the fifth intercostal space by counting the ribs. The fifth intercostal space should be located between the fifth and sixth ribs. If you're taking the apical pulse on a female, you can use three fingers to feel directly below the left breast. Usually, this same method will work on a man, as well. This allows you to take the pulse without counting the ribs.

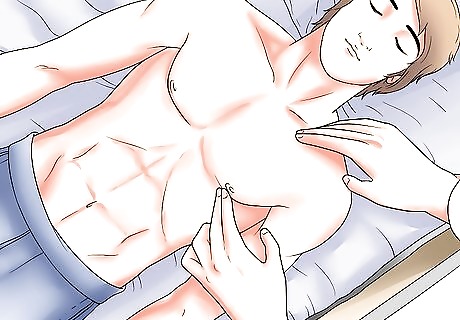

Draw an imaginary line from the middle of the left clavicle through the nipple. This is called the midclavicular line. The apical pulse can be felt and heard at the intersection of the fifth intercostal space and the midclavicular line.

Decide between using regular touch or a stethoscope. The apical pulse can be taken by touch or by using a stethoscope. It can be very difficult to feel an apical pulse, especially in women where breast tissue may lie over the pulse. A stethoscope may be easier for this purpose. In most people, it's almost impossible to feel an apical pulse using just your fingers. Unless the person is upset or in shock, their apical pulse will likely be too faint to detect without a stethoscope.

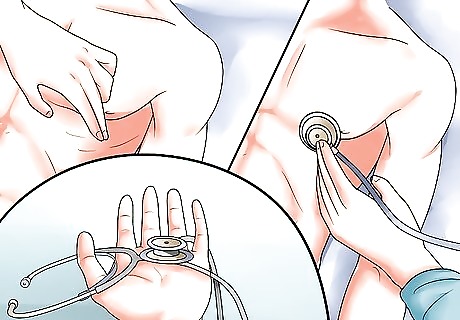

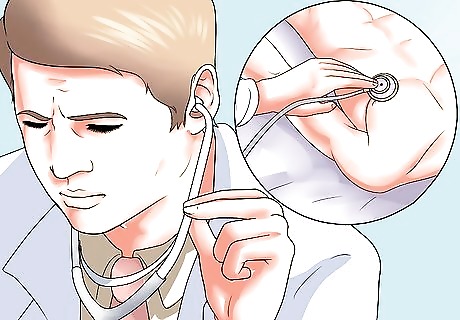

Prepare your stethoscope. Put on your stethoscope by putting the earpieces into your ears. Hold the diaphragm, which is the part of the stethoscope you use to listen to the patient's chest, in your hand. Rub the diaphragm (the end of the stethoscope) a bit to warm it up and tap it to make sure that you can hear the noises through the diaphragm. If you can't hear anything through the diaphragm, check that it is tightly attached to the stethoscope. If it's loose, you may not hear anything.

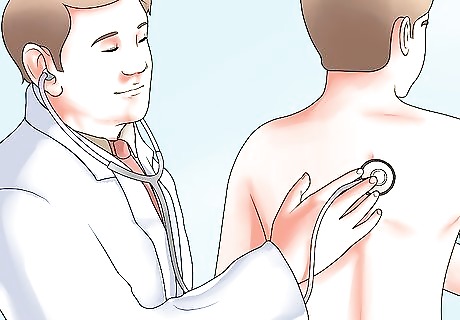

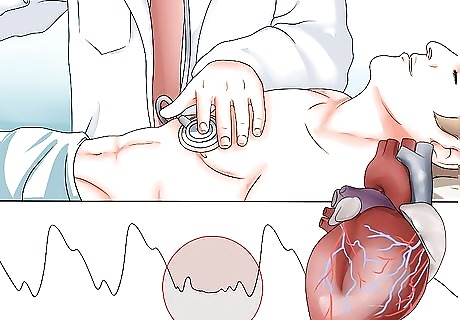

Place the stethoscope on the spot where you found the apical pulse. Tell the person to breathe normally through his or her nose because doing so will decrease the sound of the breath and make hearing the heart easier. You should hear two sounds: lub and dub. This is considered one beat. Ask the person to face away from you, which can make it easier for you to hear. A heartbeat usually sounds like a galloping horse.

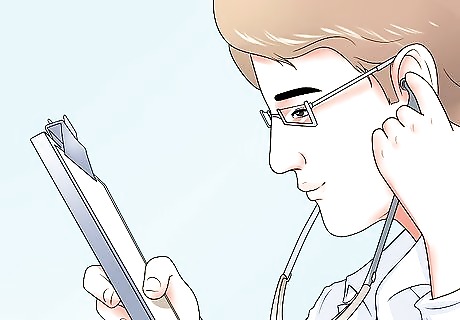

Count how many lub-dub sets you hear in one minute. This is the pulse rate, or heart rate. Think about how you might describe the pulse. Is it loud? Strong? Is the rhythm regular, or does it seem irregular?

Find the person’s heart rate. Be ready with a watch that has a second hand so you can count the pulse rate. Count how many “lub-dubs” you hear in a minute (60 seconds). The normal pulse rate for adults is 60 – 100 beats per minute. It differs with children. With newborns to three years old, the normal heart rate is 80-140. For four to nine year olds, 75-120 is a normal heart rate. For 10 to 15 years old, 50-90 beats per minute is the normal pulse rate.

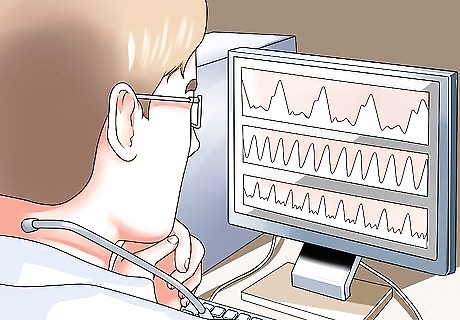

Interpreting Your Findings

Understand that interpreting heartbeats can be challenging. Interpreting a pulse, especially an apical pulse, is an art. However, there are many things that one can learn from an apical pulse. These are outlined in the following steps.

Determine if the heartbeat you hear is slow. If the pulse rate is very slow, it could be a normal adaptation for somebody who is in good shape. Some medicines also make the heart beat slower; this is especially true for elderly patients. One classic example of this is the class of drugs called beta-blockers (like metoprolol). These are commonly used to treat high blood pressure, and can slow down the heart rate. A slow heart beat can be either strong or weak. A strong heart beat is a sign of health.

Consider if the pulse you hear is very fast. If the pulse rate is very fast, it could be normal for someone exercising. Children also have much higher pulse rates than adults do. It could also be a sign of: High blood pressure, heart disease, or infection.

Consider the likelihood that the heartbeat is displaced. The apical pulse may be displaced (meaning it is to the left or the right of where it should be). Obese individuals or pregnant people may have their apical pulse shifted to the left, as the heart gets shifted with extra contents in the abdomen. Heavy smokers with lung disease may have the apical pulse displaced to the right. This is because with lung disease, the diaphragm is pulled down to get as much air as possible to the lungs, and in this process the heart gets pulled down and to the right. If you suspect a displaced heartbeat, move your stethoscope to the side and check the pulse again.

Notice if the pulse is irregular. Consider if the heartbeat seems unsteady or as though it's skipping beats. There are many potential causes of an irregular heartbeat, some of which are temporary and not harmful. An irregular heartbeat may be caused by heart disease, high blood pressure, smoking, stress, drug use, caffeine consumption, medications, and medical conditions like diabetes or sleep apnea.

Learning More About Pulses

Know what a pulse is. A pulse is a palpable and/or audible heartbeat. Pulses are most commonly assessed as pulse rate, which is a measurement of how fast an individual’s heart is beating, measured in beats per minute. A normal pulse rate is between 60 and 100 beats per minute. Pulse rates faster or slower than this may indicate a problem or disease. They also may be normal for some individuals. For instance, highly trained athletes frequently have very low pulse rates, while someone exercising may have a heart rate higher than 100. In both of these cases, the heart rates are respectively lower or higher than one might expect in most situations, but do not represent a problem. If you're checking the pulse of an athlete, ask them if they know their average resting heart rate.

Understand that pulses can also be analyzed by how they feel. Is it a smooth beat, or does it seem weak? Is the pulse bounding, meaning that it feels stronger than usual? Weak pulses may indicate that someone has low blood volume in their vessels, making the pulse harder to feel. For example, a bounding pulse might happen when someone is afraid or has just gone running.

Know where pulses are found. There are many places on the body where one can feel a pulse. Some of these include: The carotid pulse: Located in the neck on either side of the trachea, the stiff tube in the front of the neck. The carotid arteries are paired, and carry blood to the head and neck. The brachial pulse: Located inside the elbow. The radial pulse: Felt on the wrist at the base of the thumb on the palmar surface of the hand. The femoral pulse: Felt in the groin, in the fold between the leg and the torso. The popliteal pulse: Behind the knee. The posterior tibial pulse: Located at the ankle on the inner side of the leg, just behind the medial malleolus (the bump at the base of the lower leg). The pedal pulse: On the top of the foot, in the center. This pulse is often difficult to feel.

Comments

0 comment