views

- Examine the shape, color, glaze, and reign mark on the vase. If they all date to the same dynasty or era, the vase is likely authentic.

- Look for signs of genuine aging like tiny rust spots, glaze contractions, or yellowing crackles. The glaze and paint should be intact.

- Ask for a certified certificate of authenticity or provenance before purchasing an antique Chinese vase.

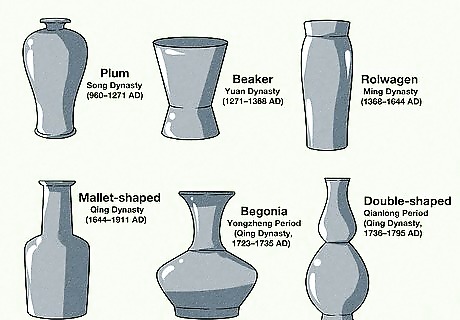

Shape

Match the vase shape to the dynasty when it was first made or popular. This will give you an idea of how old the vase is and is the first step in determining its value. Vase shapes changed with the dynasties, but tradition and limited artistic freedom under imperial rule resulted in relatively few identifiable shapes. Some well-known vase shapes by dynasty (and their possible value if authenticated) include: Song Dynasty (960–1271 AD): Plum Vase, Pear-shaped Vase, Cong-shaped Vase, and Double-Gourd Vase ($1,700-6,400). Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 AD): Beaker or Flaring Vase and Garlic-Mouth or Garlic-Head-shaped Vase ($5,800-37,000). Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD): Moonflask or Pilgrim Flask Vase, Globular Vase, and Sleeve or Rolwagen Vase ($1,200-1,800). Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 AD): Willow Leaf Vase, Rouleau Vase, Phoenix-Tail or Yen-Yen Vase, and Mallet-Shaped Vase ($5,500-42,500). Yongzheng Period (Qing Dynasty, 1723–1735 AD): Lobed or Begonia-Shaped Vase and Pomegranate Vase. Qianlong Period (Qing Dynasty, 1736–1795 AD): Double or Conjoined Vase, Hundred Deer Vase, or Rotating Vase.

Paint

Look for impurities, blotching, and different shades of blue paint. Blue paint was created from local or imported cobalt, depending on what was available at the time of production. Compare the paint used on the vase to its shape—if they come from the same time period, the vase may be authentic and potentially valuable. For example, Ming Dynasty blues look slightly blotchy because the cobalt clumped together, whereas late Qing Dynasty blues have a uniform hue. Besides the typical blue paint on white porcelain, some ancient vases use red paint or a red and green underglaze. Each source of cobalt contained different mineral impurities, meaning vases can be dated based on the look, flaws, and chemical composition of the paint.

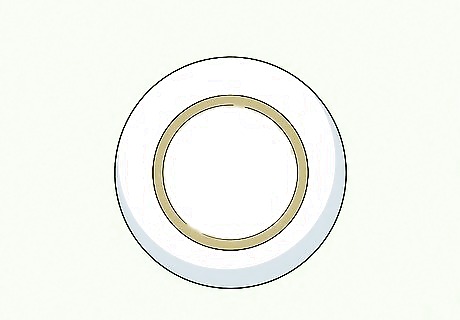

Foot Rim

Pay attention to the shape, color, and texture of the vase’s foot rim. Once you’ve determined the approximate age of the vase based on its shape and paint, compare its rim to photos of vase rims from the same period online. If the rim doesn’t match those images, there’s a 99% chance it was forged. Often, the foot rim is the final confirmation of whether the vase is authentic. For example: Early Qing Dynasty vases have smoother, denser, and whiter foot rims than in the late Qing era. Vases made between the late Ming Dynasty and the Transition Period have a super-white paste and visible knife trims on the underside. Some vases may also show small notches around the base from pernettes (ceramics stilts) used to support the vases during firing.

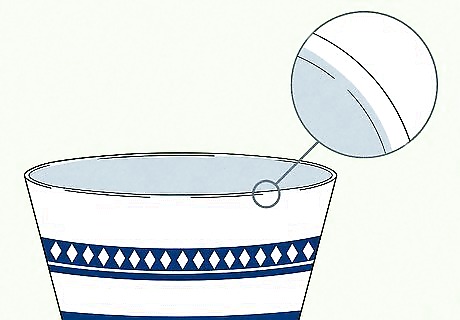

Glaze

Check if the glaze style comes from the same era as the shape and paint. Glazes vary widely from dynasty to dynasty and can be different colors, textures, or made from different ingredients. This makes them fairly easy to identify. Look out for recognizable glazes, including: Three-colored vases: These vases have a distinct green, amber, and creamy white color (Tang Dynasty, 618–907 AD). Monochromatic vases: Look for silver, white, gray, or jade tones covering the entire vase (Song Dynasty, 960–1279 AD). Celadon vases: These vases mostly appear pale jade, but they can also be pale gray, ivory, or blue (Tang era, 618 – 684 AD). Crackle vases: Look for crackles in the glaze made by the rapid cooling technique used in the Song Dynasty and afterward (960–1279 AD). Blue and white vases with clear glaze: This style emerged in the 9th century, but is most associated with the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD). Flambé glaze: Look for red, purple, or bluish tones from the copper in the glaze. Jun vases: These have a blue tone with hints of purple. Look for fine cracks in the glaze to prove its authenticity (Tang and Song Dynasties). Five-colored vases: The glaze during the Kangxi period (1662–1722 AD) uses enamel to achieve striking bright colors, like peach or pink.

Porcelain

See if the porcelain is thin, durable, and made of kaolin. Kaolin is a type of clay found abundantly in China—if the vase is made of another material, it’s not authentic Chinese porcelain. Check for thinness (the porcelain should be nearly translucent). This means the clay was fired for a long time and is considered high grade (and more valuable). Porcelain from the 18th century should be flawless since this was the peak of ceramic production in China. Earlier vases may have miniscule defects.

Decorations and Imagery

Examine the artwork on the vase for evidence of stenciling or distortion. This indicates that the imagery was copied from a 2-D photo of a vase and that the one you’re looking at is not genuine or valuable. Look for images that appear flat and stretched out, for example, or that have black stenciling outlines. Ill-defined or blurry details are signs of poor copying, too. Flowers are the most common design motif on Chinese vases. Popular images include peonies, crab apple trees, hibiscus, roses, orchids, lotus, and jasmine. If a vase doesn’t have decorations that were common in the Song Dynasty or later, it’s likely not genuine.

Aging

Look for signs of genuine aging versus faked aging by forgers. Authentic vases age very well, so pieces showing excessive wear and tear are likely modern pieces that were altered to seem older (and therefore more valuable). Look out for the following genuine porcelain aging characteristics. The better the condition of the vase, the more money it will be worth. Discoloration: Glaze or paint shouldn't show significant discoloration unless the vase was in the soil or sea for hundreds of years. Crackles in the glaze: Crackles are often added by forgers, but genuine antique crackles may turn yellow or brown over time. Rust spots: Look for tiny spots of rust on the surface of ancient vases caused by iron residue moving to the surface of the ceramic. Glaze contractions: Search for small holes or recesses in the surface of the porcelain. These indicate the vase was made prior to the 18th century. On-glaze decorations: Vases with paint over the first coat of glaze may show discoloration if the vase was used for storage.

Reign Mark

Find the 4-6 character reign mark on the base, body, or neck of the vase. Reign marks indicate who was emperor when the vase was made and are usually blue or red. Translate the mark and check if that emperor actually ruled during the era indicated by the vase’s other characteristics. If there’s a match and the mark was added during their reign, the vase will likely be valued near the top of its expected range. Sometimes, the reign mark names the correct emperor but was added later. These marks are called apocryphal and are less valuable than originals. Experts examine the shade of cobalt blue used to make the mark to determine legitimacy. Some also test the calligraphy strokes for authenticity. Not all genuine vases have a reign mark.

Weight and Feel

Compare the weight and feel to other authentic vases you've handled. Forgers can’t tell the weight of thin, authentic porcelain based on photos, so fakes are often far too heavy. Feel the glaze, too—if it’s chipped, pitted, or worn down, it is likely not original (authentic glaze is very durable). Thicker, heavier vases might be Japanese porcelain marketed as Chinese to trick unknowing buyers. Experts can also examine the glaze for forced aging techniques like acid baths, refiring, and adding fake staple repairs. Some forgers use traditional production methods to create era-appropriate glazes or porcelain.

History of Ownership

Ask for the vase’s ownership records (provenance) or auction labels. If an antique vase comes from a reputable collection or has been passed down through generations, its value will skyrocket. Forgers recognize this, so don’t assume the records are legitimate right away. Consider these factors when examining a vase’s past ownership: Certificates of Authenticity from Hong Kong during the 1980s aren’t considered reliable evidence of provenance. From 1954, true antiques made before 1795 cannot legally be removed from China unless they’re affixed with a red wax seal deeming them culturally unimportant. If ownership records claim a vase is ancient and valuable but the vase has a seal, the records may be false.

Appraisal

Consult an expert to determine the vase’s authenticity, age, and value. Because of the wide variety of Chinese vases, many appraisers specialize in work from a specific period. Talk to an expert in the style of vase you’re curious about to get the most accurate information. Sometimes, you can submit photos and other information through an online form to get expert feedback.

Comments

0 comment