views

Treating Mastitis in a Goat

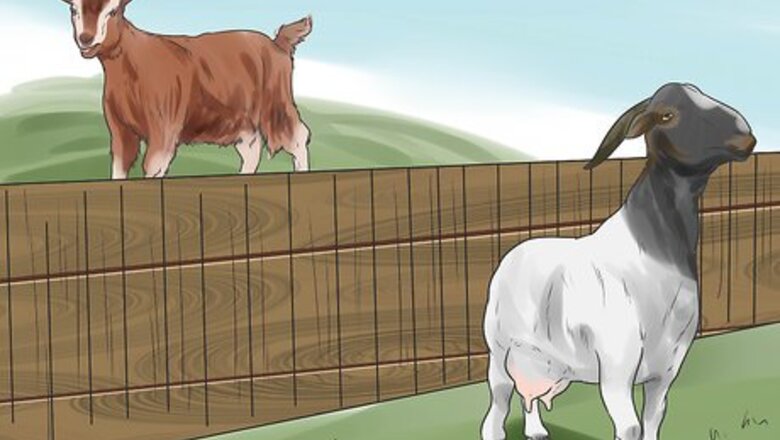

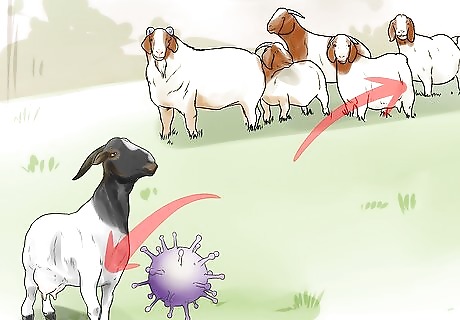

Isolate the affected goat(s). If one or more of your goats have mastitis, you'll want to separate the affected goats from the rest of the herd. Some farmers go so far as to cull affected animals to further reduce the chances of a mastitis outbreak. Keeping affected goats in the herd risks the health of other goats and increases the chances that you may accidentally collect milk from a goat with mastitis.

Dry off the teat. If your goat has mastitis, the first thing you'll need to do is dry off the teat. Drying off a teat means inducing a period of non-lactation so that the infection can be treated and the mammary tissue can rest and regenerate. Drying off should ideally begin about two weeks before the desired dry-off date, but since mastitis probably came on unexpectedly you can begin drying off right away. Gradually reduce the energy content of the goat's diet and replace it with a high-fiber diet. The goat's body will recognize that there are fewer nutrients available and milk production will slow down. Try cutting out grain from the goat's diet and replacing alfalfa with grass hay. High-production goats may need an even lower-calorie diet like straw and water, though grass hay is usually sufficient. Don't limit the amount of food or water your goat has. When livestock has less access to food and water they tend to seek out any other food sources they can find, which may lead to eating toxic plants or fighting over resources.

Use an effective teat dip. The goat's teats should be cleaned with an antiseptic to kill any external pathogens living on the udder. A product containing either iodine or chlorhexidine is considered the most effective treatment, as well as one of the most common. If using chlorhexidine, choose a product with a 2% concentration. Apply the antiseptic twice at 24-hour intervals for maximum effectiveness. Fill a 12 cc or 20 cc plastic syringe casing with the teat dip. Submerge the teat inside the casing after you disinfect it.

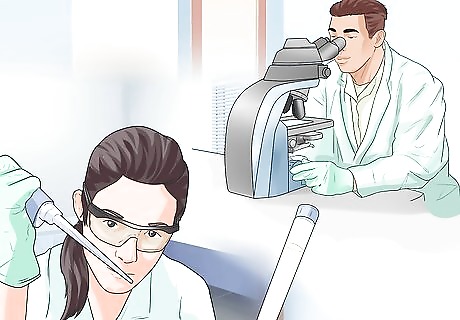

Identify the pathogen causing mastitis. Your vet will most likely run tests on the goat's milk and/or blood to identify the specific pathogen causing the infection. The pathogen affecting your goat will determine which (if any) medications your vet may prescribe, and it may influence your vet's outlook on the goat's recovery period. Coagulase-negative staphylococci are one of the most prevalent pathogens that cause mastitis. Staphylococcus aureus infections are fairly uncommon, but when they occur they tend to be persistent and do not respond well to treatment. Streptococcus agalactiae infections are very uncommon and are generally not thought of as a risk for goat mastitis. Mycoplasma infections can cause significant problems in goats and may lead to more severe health problems like septicemia, polyarthritis, pneumonia, or encephalitis.

Administer medication to your goat. Depending on the results of a milk culture, your veterinarian may recommend a course of medication to treat the mastitis. Antibiotics are commonly prescribed, but you will have to discontinue use once the infection clears and test the milk to ensure there are no antibiotics present before you resume milking. Antibiotics like benzylpenicillin, cloxacillin, amoxicillin, cephalonium, cefoperazone, erythromycin, tilmicosin, kanamycin, penicillin, ampicillin, or tetracycline can all be used to treat mastitis. Many goats will eat an oral medication in their food. Use a balling gun to give the medication into the back of the goat’s throat. Glucocorticoids like dexamethasone may be administered to reduce swelling. Intramammary antibiotic ointment may also be administered to the teats, but you'll need to keep an eye on the goat to make sure her skin does not get irritated.

Diagnosing a Case of Mastitis

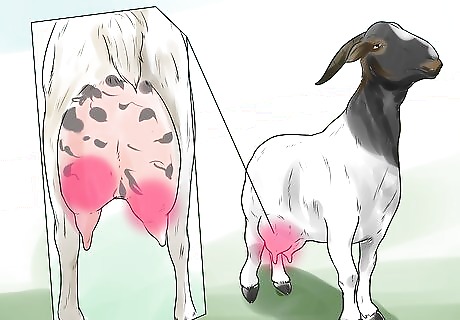

Look for the clinical signs of mastitis. Mastitis usually comes on as either a systemic form or a chronic form. The systemic form develops very quickly and presents symptoms like high fever (above 105 degrees Fahrenheit, or 40.5 degrees Celsius) and an elevated pulse. The chronic form of mastitis typically develops as a persistent and often-incurable infection. Acute mastitis is marked by hard, swollen, reddish mammary glands, as well as milk secretions that are watery and yellowish (due to the presence of white blood cells). Chronic mastitis is usually marked by hard lumps on the udder and may be accompanied by an inability to produce milk and a hot feeling to the touch.

Run tests on the affected goat. Common tests your vet may order include a microbiologic milk culture, a somatic cell count (SCC), the California Mastitis Test (CMT), or an Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA) test. The SCC and the CMT are the two most frequently-used tests to identify cases of mastitis. Be aware that negative bacterial cultures do not necessarily mean that there is not a case of bacterial mastitis. Many types of bacteria are shed cyclically and therefore may not show up in a milk sample.

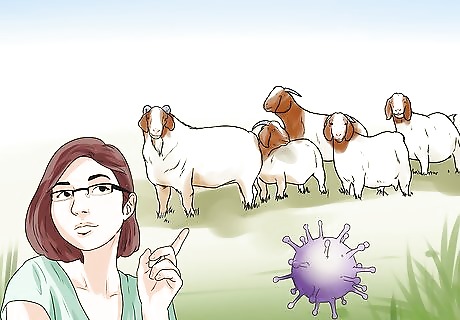

Extrapolate information based on the herd's history and behavior. If one or more goats in your herd have mastitis, it's very likely that other goats have been exposed to mastitis as well. Once you've identified and isolated an affected goat, you may want to keep a regular checkup of your other goats' udders, milk, and body temperature to watch for signs that the infection has spread.

Preventing Future Cases of Mastitis

Improve pre-milking hygiene. Improving the hygiene of pre-milking and milking conditions can significantly decrease the rate of mastitis transmission. This includes better sanitation and cleanliness in the goats' housing and in the milking area. Goats should not be overcrowded. Every goat should have sufficient room in the barn as well as in the yard. The paths between your milking area and the goats' housing or fields should be kept clean. The paths should be free-draining and should be kept clear of feces and slurry. Do a dry wipe and a thorough washing of the udders and teats with clean, potable water. Make sure you also wash your hands before and after milking. Use teat dips and sprays to disinfect the mammary glands before milking, and keep any milking equipment you use clean and sanitary.

Reduce the amount of time goats are milked. Some preliminary studies suggest that there may be a link between mastitis outbreaks and the amount of time that goats are attached to milking units. Though this may not conclusively prevent cases of mastitis, it is worth further consideration and it may warrant minimizing the time spent hooked up to a milking unit.

Identify and segregate or cull affected goats. If any of your goats have mastitis, they should not be kept with the rest of the herd. Most sanitation and mastitis-prevention regimens recommend either isolating the affected goats from the herd or culling them to prevent recurring outbreaks.

Comments

0 comment