views

X

Research source

You will probably need a college level class to understand calculus well, but this article can get you started and help you watch for the important concepts as well as technical insights.

Reviewing the Basics of Calculus

Know that calculus is the study of how things are changing. Calculus is a branch of mathematics that looks at numbers and lines, usually from the real world, and maps out how they are changing. While this might not seem useful at first, calculus is one of the most widely used branches of mathematics in the world. Imagine having the tools to examine how quickly your business is growing at any time, or plotting the course of a spaceship and how fast it is burning fuel. Calculus is an important tool in engineering, economics, statistics, chemistry, and physics, and has helped create many real-world inventions and discoveries.

Remember that functions are relationships between two numbers, and are used to map real-world relationships. Functions are rules for how numbers relate to one another, and mathematicians use them to make graphs. In a function, every input has exactly one output. For example, in y = 2 x + 4 , {\displaystyle y=2x+4,} y=2x+4, every value of x {\displaystyle x} x gives you a new value of y . {\displaystyle y.} y. If x = 2 , {\displaystyle x=2,} x=2, then y = 8. {\displaystyle y=8.} y=8. If x = 10 , {\displaystyle x=10,} x=10, then y = 24. {\displaystyle y=24.} y=24. All calculus studies functions to see how they change, using functions to map real-world relationships. Functions are often written as f ( x ) = x + 3. {\displaystyle f(x)=x+3.} f(x)=x+3. This means that the function f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} f(x) always adds 3 to the number you input for x . {\displaystyle x.} x. If you want to input 2, write f ( 2 ) = ( 2 ) + 3 , {\displaystyle f(2)=(2)+3,} f(2)=(2)+3, or f ( 2 ) = 5. {\displaystyle f(2)=5.} f(2)=5. Functions can map complex motions too. NASA, for example, has a function that describes how fast a rocket will go based on how much fuel it burns, the wind resistance, and the weight of the rocket itself.

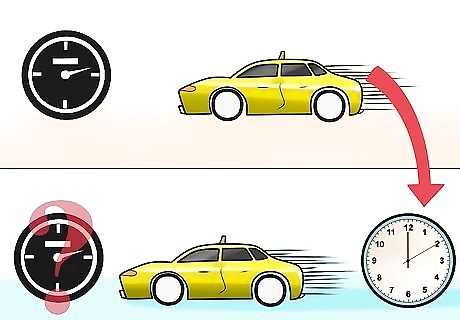

Think about the concept of infinity. Infinity is when you repeat a process over and over again. It is not a specific place (you can’t go to infinity), but rather the behavior of a number or equation if it is done forever. This is important to study change: you might want to know how fast your car is moving at any given time, but does that mean how fast you were at that current second? Millisecond? Nanosecond? You could find infinitely smaller amounts of time to be extra precise, and that is where calculus comes in.

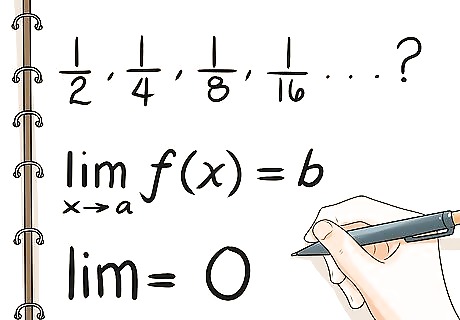

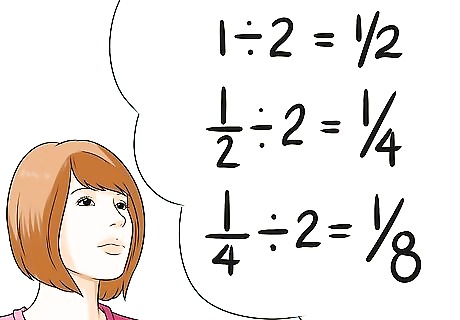

Understand the concept of limits. A limit tells you what happens when something is near infinity. Take the number 1 and divide it by 2. Then keep dividing it by 2 again and again. 1 would become 1/2, then 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, 1/32, and so on. Each time, the number gets smaller and smaller, getting “closer” to zero. But where would it end? How many times do you have to divide by 1 by 2 to get zero? In calculus, instead of answering this question, you set a limit. In this case, the limit is 0. Limits are easiest to see on a graph – are the points that a graph almost touches, for example, but never does? Limits can be a number, infinity, or not even exist. For example, if you add 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + ... forever, your final number would be infinitely large. The limit would be infinity.

Review essential math concepts from algebra, trigonometry, and pre-calculus. Calculus builds on many of the forms of math you’ve been learning for a long time. Knowing these subjects completely will make it much easier to learn and understand calculus. Some topics to refresh include: Algebra. Understand different processes and be able to solve equations and systems of equations for multiple variables. Understand the basic concepts of sets. Know how to graph equations. Geometry. Geometry is the study of shapes. Understand the basic concepts of triangles, squares, and circles and how to calculate things like area and perimeter. Understand angles, lines, and coordinate systems Trigonometry. Trigonometry is branch of maths which deals with properties of circles and right triangles. Know how to use trigonometric identities, graphs, functions, and inverse trigonometric functions.

Purchase a graphing calculator. Calculus is not easy to understand without seeing what you are doing. Graphing calculators take functions and display them visually for you, allowing you to better comprehend the equations you are writing and manipulating. Oftentimes, you can see limits on the screen and calculate derivatives and functions automatically. Many smartphones and tablets now offer cheap but effective graphing apps if you do not want to buy a full calculator.

Understanding Derivatives

Know that calculus is used to study “instantaneous change.” Knowing why something is changing at an exact moment is the heart of calculus. For example, calculus tells you not only the speed of your car, but how much that speed is changing at any given moment. This is one of the simplest uses of calculus, but it is incredibly important. Imagine how useful that knowledge would be for the speed of a spaceship trying to get to the moon! Finding instantaneous change is called differentiation. Differential calculus is the first of two major branches of calculus.

Use derivatives to understand how things change instantaneously. A "derivative" is a fancy sounding word that inspires anxiety. The concept itself, however, isn't that hard to grasp -- it just means "how fast is something changing." The most common derivatives in everyday life relate to speed. You likely don’t call it the “derivative of speed,” however – you call it "acceleration." Acceleration is a derivative – it tells you how fast something is speeding up or slowing down, or how the speed is changing.

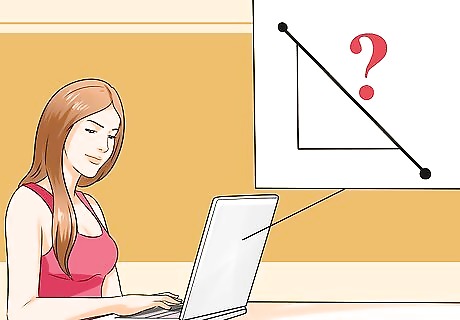

Know that the rate of change is the slope between two points. This is one of the key findings of calculus. The rate of change between two points is equal to the slope of the line connecting them. Think of a basic line, such as the equation y = 3 x . {\displaystyle y=3x.} y=3x. The slope of the line is 3, meaning that for every new value of x , {\displaystyle x,} x, y {\displaystyle y} y changes by 3. The slope is the same thing as the rate of change: a slope of three means that the line is changing by 3 for every change in x . {\displaystyle x.} x. When x = 2 , y = 6 ; {\displaystyle x=2,y=6;} x=2,y=6; when x = 3 , y = 9. {\displaystyle x=3,y=9.} x=3,y=9. The slope of a line is the change in y divided by the change in x. The bigger the slope, the steeper a line. Steep lines can be said to change very quickly. Review how to find the slope of a line if your memory is hazy.

Know that you can find the slope of curved lines. Finding the slope of a straight line is relatively straightforward: how much does y {\displaystyle y} y change for each value of x ? {\displaystyle x?} x? Yet complex equations with curves, like y = x 2 {\displaystyle y=x^{2}} y=x^{{2}} are much harder to find. However, you can still find the rate of change between any two points – simply draw a line between them and calculate the slope. For example, in y = x 2 , {\displaystyle y=x^{2},} y=x^{{2}}, you can take any two points and get the slope. Take ( 1 , 1 ) {\displaystyle (1,1)} (1,1) and ( 2 , 4 ) . {\displaystyle (2,4).} (2,4). The slope between them would equal 4 − 1 2 − 1 = 3 1 = 3. {\displaystyle {\frac {4-1}{2-1}}={\frac {3}{1}}=3.} {\frac {4-1}{2-1}}={\frac {3}{1}}=3. This means that the rate of change between x = 1 {\displaystyle x=1} x=1 and x = 2 {\displaystyle x=2} x=2 is 3.

Make your points closer together for a more accurate rate of change. The closer your two points, the more accurate your answer. Say you want to know how much your car accelerates right when you step on the gas. You don’t want to measure the change in speed between your house and the grocery store, you want to measure the change in speed the second after you hit the gas. The closer your measurement is to that split-second moment, the more accurate your reading will be. For example, scientists study how quickly some species are going extinct to try to save them. However, more animals often die in the winter than the summer, so studying the rate of change across the entire year is not as useful – they would find the rate of change between closer points, like from July 1st to August 1st.

Use infinitely small lines to find the “instantaneous rate of change,” or the derivative. This is where calculus often becomes confusing, but this is actually the result of two simple facts. First, you know that the slope of a line equals how quickly it is changing. Second, you know that closer the points of your line are, the more accurate the reading will be. But how can you find the rate of change at one point if slope is the relationship of two points? The answer: you pick two points infinitely close to one another. Think of the example where you keep dividing 1 by 2 over and over again, getting 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, etc. Eventually you get so close to zero, the answer is "practically zero." Here, your points get so close together, they are "practically instantaneous." This is the nature of derivatives.

Learn how to take a variety of derivatives. There are a lot of different techniques to find a derivative depending on the equation, but most of them make sense if you remember the basic principles of derivatives outlined above. All derivatives are is a way to find the slope of your "infinitely small" line. Now that your know the theory of derivatives, a large part of the work is finding the answers.

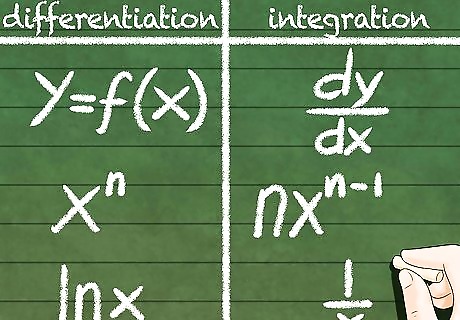

Find derivative equations to predict the rate of change at any point. Using derivatives to find the rate of change at one point is helpful, but the beauty of calculus is that it allows you to create a new model for every function. The derivative of y = x 2 , {\displaystyle y=x^{2},} y=x^{{2}}, for example, is y ′ = 2 x . {\displaystyle y^{\prime }=2x.} y^{{\prime }}=2x. This means that you can find the derivative for every point on the graph y = x 2 {\displaystyle y=x^{2}} y=x^{{2}} simply by plugging it into the derivative. At the point ( 2 , 4 ) , {\displaystyle (2,4),} (2,4), where x = 2 , {\displaystyle x=2,} x=2, the derivative is 4, since y ′ = 2 ( 2 ) . {\displaystyle y^{\prime }=2(2).} y^{{\prime }}=2(2). There are different notations for derivatives. In the previous step, derivatives were labeled with a prime symbol – for the derivative of y , {\displaystyle y,} y, you would write y ′ . {\displaystyle y^{\prime }.} y^{{\prime }}. This is called Lagrange's notation. There is also another popular way of writing derivatives. Instead of using a prime symbol, you write d d x . {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}.} {\frac {{\mathrm {d}}}{{\mathrm {d}}x}}. Remember that the function y = x 2 {\displaystyle y=x^{2}} y=x^{{2}} depends on the variable x . {\displaystyle x.} x. Then, we write the derivative as d y d x {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} y}{\mathrm {d} x}}} {\frac {{\mathrm {d}}y}{{\mathrm {d}}x}} – the derivative of y {\displaystyle y} y with respect to x . {\displaystyle x.} x. This is called Leibniz's notation.

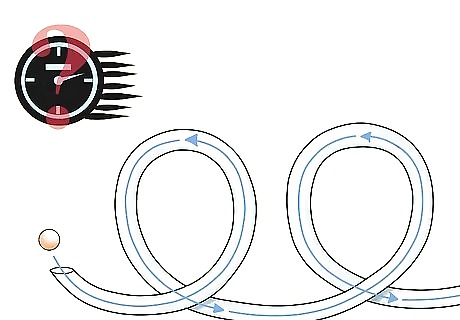

Remember real-life examples of derivatives if you are still struggling to understand. The easiest example is based on speed, which offers a lot of different derivatives that we see every day. Remember, a derivative is a measure of how fast something is changing. Think of a basic experiment. You are rolling a marble on a table, and you measure both how far it moves each time and how fast it moves. Now imagine that the rolling marble is tracing a line on a graph – you use derivatives to measure the instantaneous changes at any point on that line. How fast does the marble change location? What is the rate of change, or derivative, of the marble’s movement? This derivative is what we call “speed.” Roll the marble down an incline and see how fast in gains speed. What is the rate of change, or derivative, of the marble’s speed? This derivative is what we call “acceleration.” Roll the marble along an up and down track like a roller coaster. How fast is the marble gaining speed down the hills, and how fast is it losing speed going up hills? How fast is the marble moving exactly halfway up the first hill? This would be the instantaneous rate of change, or derivative, of that marble at its one specific point.

Understanding Integrals

Know that you use calculus to find complex areas and volumes. Calculus allows you to measure complex shapes that are normally too difficult. Think, for example, about trying to find out how much water is in a long, oddly shaped lake – it would be impossible to measure each gallon of water separately or use a ruler to measure the shape of the lake. Calculus allows you to study how the edges of the lake change, and use that information to learn how much water is inside. Making geographic models and studying volume is using integration. Integration is the second major branch of calculus.

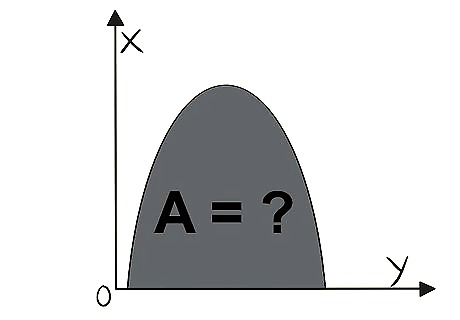

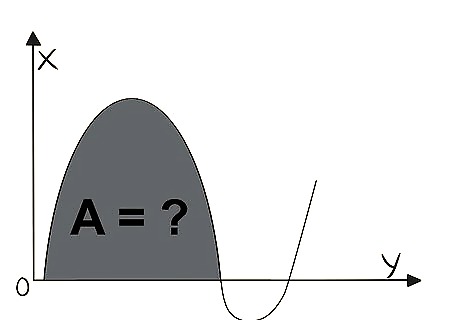

Know that integration finds the area underneath a graph. Integration is used to measure the space underneath any line, which allows you to find the area of odd or irregular shapes. Take the equation y = 4 − x 2 , {\displaystyle y=4-x^{2},} y=4-x^{{2}}, which looks like an upside-down “U.” You might want to find out how much space is underneath the U, and you can use integration to find it. While this may seem useless, think of the uses in manufacturing – you can make a function that looks like a new part and use integration to find out the area of that part, helping you order the right amount of material.

Know that you have to select an area to integrate. You cannot just integrate an entire function. For example, y = x {\displaystyle y=x} y=x is a diagonal line that goes on forever, and you cannot integrate the whole thing because it would never end. When integrating functions, you need to choose an area, such as [ 2 , 5 ] {\displaystyle [2,5]} {\displaystyle [2,5]} (all x-values between and including 2 and 5).

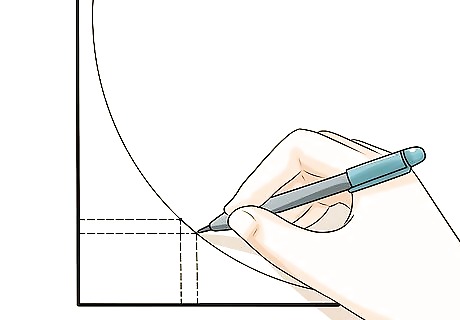

Remember how to find the area of a rectangle. Imagine you have a flat line above a graph, like y = 4. {\displaystyle y=4.} y=4. To find the area underneath it, you would be finding the area of a rectangle between y = 0 {\displaystyle y=0} y=0 and y = 4. {\displaystyle y=4.} y=4. This is easy to measure, but it will never work for curvy lines that cannot be turned into rectangles easily.

Know that integration adds up many small rectangles to find area. If you zoom in very close to a curve, it looks flat. This happens every day – you cannot see the curve of the earth because we are so close to its surface. Integration makes an infinite number of little rectangles under a curve that are so small they are basically flat, which allows you to measure them. Add all of these together to get the area under a curve. Imagine you are adding together a lot of little slices under the graph, and the width of each slice is ‘’almost’’ zero.

Know how to correctly read and write integrals. Integrals come with 4 parts. A typical integral looks like this: ∫ f ( x ) d x {\displaystyle \int f(x)\mathrm {d} x} \int f(x){\mathrm {d}}x The first symbol, ∫ , {\displaystyle \int ,} \int , is the symbol for integration (it is actually an elongated S). The second part, f ( x ) , {\displaystyle f(x),} f(x), is your function. When it is inside the integral, it is called the integrand. Finally, the d x {\displaystyle \mathrm {d} x} {\mathrm {d}}x at the end tells you what variable you are integrating with respect to. Because the function f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} f(x) depends on x , {\displaystyle x,} x, that is what you should integrate with respect to. Remember, the variable you are integrating is not always going to be x , {\displaystyle x,} x, so be careful what you write down.

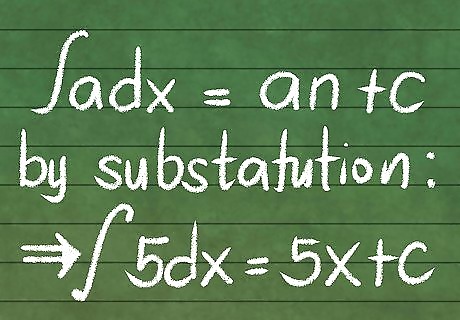

Learn how to find integrals. Integration comes in many forms, and you will need to learn a lot of different formulas to integrate every function. However, they all follow the principles outlined above: integration sums up an infinite number of things. Integrate by substitution. Calculate indefinite integrals. Integrate by parts.

Know that integration reverses differentiation, and vice versa. This is an ironclad rule of calculus that is so important, it has its own name: the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. Since integration and differentiation are so closely related, a combination of the two of them can be used to find rate of change, acceleration, speed, location, movement, etc. no matter what information you have. For example, remember that the derivative of speed is acceleration, so you can use speed to find acceleration. But if you only know the acceleration of something (like objects falling due to gravity), you can integrate it to find the speed!

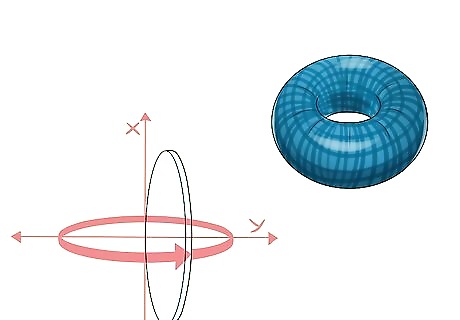

Know that integration can also find the volume of 3D objects. Spinning a flat shape around is a way to create 3D solids. Imagine spinning a coin on the table in front of you – notice how it appears to form a sphere as it spins. You can use this concept to find volume in a process known as “volume by rotation.” This lets you find the volume of any solid in the world, as long as you have a function that mirrors it. For example, you can make a function that traces the bottom of a lake, and then use that to find the volume of the lake, or how much water it holds.

Comments

0 comment