views

Late last month, a computer console lit up at a National Technical Research Organisation listening station, recording a stream of zeroes and ones being beamed to a satellite hundreds of kilometres above the earth from the windswept 4,400 metre high Barahoti plain, some 15 kilometres inside the Line of Actual Control as it cuts through Uttarakhand, dividing it from Tibet’s Ngari Prefecture.

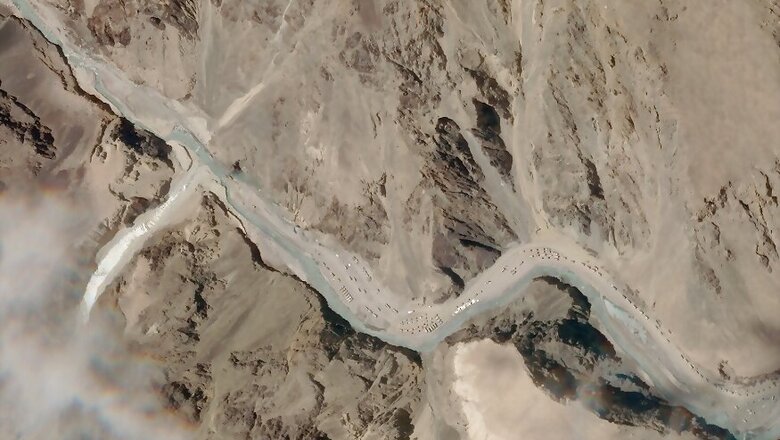

Even as the satellite-phone traffic was detected, China and India had begun to defuse the months-long crisis at the LAC. Based on commitments made in military-to-military talks, and revealed by News18 last week, the PLA has dismantled some earthworks along the Galwan River, pulled back troops, and begun thinning out forces.

National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi—the two countries’ special representatives on China-India border issues—now have before them a task even tougher than arriving at a formula that will allow the two armies to complete the disengagement process at more bitterly-contested sites, like the ridges stretching out from the Pangong lake, or the Depsang plains.

“The crisis in Galwan should have brought home to Beijing the risk that its behaviour on the LAC could spark off a war in the Himalaya,” one senior government official familiar with the negotiations told News18. “The real question is: are they willing to change it?”

For Indian communications-intelligence technicians, the satellite-phone blips detected in Barahoti are part of an alarmingly-familiar pattern. In recent weeks, similar satellite-phone traffic has been reported from over ten kilometres on the Indian side of the LAC near the Shipki La pass in Himachal Pradesh’s Kinnaur—an ancient trading post which saw some Rs 9.7 crore in business during the 2019 season.

“The PLA knows perfectly well that we listen-in to their communications,” one senior intelligence official said. “These Thuraya satellite phone calls are basically their way of telling us: ‘Look, we’re here’”.

Intrusions like these have become increasingly common since 2013, when the PLA pitched tents on the Depsang plains near Burtsé, asserting that the LAC ran well to the west of India’s claims. The PLA’s presence was used to block Indian patrols headed out to an arc of positions along the LAC, code-named Patrolling Point 10, 11, 12 and 13.

Even though the 2013 crisis was ended through negotiations, Indian troops and the PLA have periodically faced-off in the region—and patrols have been blocked again as the Galwan crisis has unfolded, military sources said.

In 2014 and 2015, face-offs again erupted along the LAC in Ladakh. Then, in 2016, PLA troops—as well as two Zhiba WZ-9 attack helicopters—were reported to have crossed the LAC in the Barahoti area. The summer of 2017 saw the largest showdown until the Galwan crisis, in Doklam.

Experts have offered various hypothesis on why China has stepped up pressure on the LAC. For example, the Chinese scholar Yun Sun has suggested the reasons are rooted both in the PLA’s tactical concerns over India’s expansion of its border-defence infrastructure, and as a warning against New Delhi taking the United States’ side in the emerging strategic confrontation between the two superpowers.

Irrespective of the truth, both capitals were largely content to let their armies assert their claims along the LAC, believing a series of agreements would prevent border confrontations from escalating into full-blown hostilities.

The Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement, signed in September 1993, was supplemented, in 1996, with a series of military confidence-building measures and a 2005 agreement laying down rules for border patrols. There is a 2012 agreement that sets procedures out to end crisis through consultations; and there is the Border Defence Cooperation Agreement of 2013.

“Perhaps the one big lesson from this crisis is that those agreements are a band-aid, not a solution,” said scholar Manoj Joshi. “The best-case scenario now is that the two countries agree to delineate a common LAC, something China has long resisted”.

Little evidence exists, so far, for hopes the PLA is willing to engage in such an exercise. In military-to-military meetings, government sources said, there’s been no indication the PLA is even prepared to pull back from Finger 4 in Pangong. There, the PLA has built earthworks to deny Indian troops their ability to patrol from their forward positions on Finger 3 to Finger 8, which India asserts lies within the LAC.

“The two armies have agreed on various risk-reduction measures”, a senior government official said, “like avoiding sending patrols into likely flash-points, thus creating some de-facto buffer zones. But this is, obviously, not a very stable situation”.

Agreeing on where the China-India frontier actually runs isn’t an easy task, given the vagueness of colonial boundaries in the inner Himalaya.

In the summer of 1952, the Intelligence Bureau reported that “About the end of last century the Tibetans had established a Customs Post at Hoti Plain. To stop this practice, the British Government had to send out a detachment of Gurkhas along with the Deputy Collector in 1890. This had a salutary effect and the Tibetans removed their post”.

“It appears that for some time past the Tibetans have again been establishing a Police-cum-Customs post at Hoti during the trading season,” the Intelligence Bureau reported.

Those Tibetan posts formed the basis of Chinese claims that Barahoti lies in their territory—while New Delhi relies on both the British imperial practice, as well as earlier documentation, to assert the plain is in fact part of India. The dispute was to lead, in the summer of 1954, to the first of the PLA incursions into Indian-claimed territory that would explode, eventually, into the war of 1962.

“Fixing these problems is not impossible with some give-and-take”, one intelligence official says, “and every sane person realises that this issue is a millstone around the neck of both countries, which we’re best-off without”.

“The question is, however, whether Beijing is willing to engage in give-and-take, or wants to keep pushing a policy of take-and-take”.

Comments

0 comment