views

Far away from the cut and thrust of running large corporate houses, there’s something that’s keeping Azim Premji and Sunil Mittal, among the most successful entrepreneurs in India, busy. For the last almost 10 years, both have committed serious money, managers and their own time to providing quality education for India’s underprivileged children. They recognise that education has perhaps the greatest “multiplier effect”.

The government’s initiatives so far have been largely tied with the spread of compulsory education. The Rs 90,000-crore Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan and the mid day meal programmes have achieved a measure of success in bringing more children into schools. But it’s been a victory of quantity over quality. Even though 80 percent of children aged six to 14 attend government schools where education is free, they remain effectively uneducated and therefore unemployable. Absenteeism is high, as is the dropout rate and those who attend hardly benefit.

According to the Annual Status of Education Report, 2009, more than 30 percent of the children in class I do not recognise numbers and letters. Half of class V students meet reading standards of just class II.

It is this gap that Premji and Mittal hope to bridge through the work of their philanthropic organisations, the Azim Premji Foundation (APF) and the Bharti Foundation (Bharti).

APF believes the best way to make an impact is by working with the state education departments to improve learning in classrooms. The logic is simple: With 7 million education professionals (teachers and support staff) and an annual spending of $ 13.5 billion (Rs 62,000 crore), the government has already achieved scale that no private organisation could equal.

Bharti has chosen to build a parallel system of new schools -- Satya Bharti schools -- to provide quality education for free to the rural poor and set new benchmarks on how to educate children. Of course, it does still need to engage with local governments as it relies heavily on partnership from the villages. Typically, the village gives the land free on long lease on which the school is built.

It is not that these two are the only organisations working to find solutions in this field. From Intel to IBM, Deutsche Bank to ICICI Bank, companies are doing some philanthropic work in the education space. Shriram Foundation works with 25 government schools in Haryana; Thermax runs a few civic schools in Pune.

But what sets APF and Bharti apart is their scale and ambition. “What we do should be reflected in permanent, institutionalised change. It should not be an island of excellence or a one off thing,” says S. Giridhar, head, programmes, APF.

APF is already present in nine states, while Bharti has 236 schools across India and plans to take that number to 550 schools with 2 lakh children.

How can civil society engage with the government to bring large-scale systemic change? There are important lessons to be learnt from both the models.

The APF Route

APF, started with a $ 125 million (about Rs 575 crore) stock grant from Premji, was set up in 1999. To fulfil its agenda, it zeroed in on three things: One, train the teachers. A vibrant classroom would lead to better attendance and higher school completion rates. Two, build leadership skills among the education officers -- they control the resources for government schools (incentives for teachers, mid day meal programmes, supply of text books and uniforms). Three, assess children for critical thinking, not rote learning, as this has a direct bearing on the way they will be taught.

This last was validated through one of its earliest programmes, the Learning Guarantee Programme (LGP) in Karnataka (2002-05). Its aim was to showcase government schools with best practices in teaching. Schools would volunteer for assessment and would be selected if their students (classes I-IV) qualified for a threshold level of enrolment, attendance and learning. In the first year, 40 schools (4.5 percent of the participating schools) met all the criteria. By the third year, the number had gone up to 144 (7.8 percent).

APF discovered that changing the way questions were framed in exams led to a change in the way children were taught. For example, if you ask ‘What is the highest 4 digit number?’ Every child can memorise the answer, 9,999. But if you ask ‘What is the highest four digit number you can create from 7, 2, 1 and 9’, the child will need to understanding the concept of unit, tens, hundreds. Schools that participated in this exercise every year showed marked improvement in learning achievements.

Today, the programme has spread to Rajasthan, Gujarat and Uttarakhand, and is onto the next stage of its assessment-led reforms. Instead of expanding to new areas, APF is working towards improving classroom interactions in schools where LGP has been rolled out. It is working closely with the education departments to train teachers and administrators. “It’s the large government system that is actually doing the work, we are merely facilitating or helping,” says Anurag Behar, who joins as co-CEO from July 1.

The Bharti route

Set up in 2000, Bharti started with writing random cheques to help the underprivileged until one day in 2005-06 the Mittal family figured it wasn’t serving the purpose, recalls Rakesh Mittal, the eldest of the three Mittal brothers, and the head of the Bharti Foundation. “While we always talked about business and money we felt we need to look at areas where we could make a difference,” he says. So, the Mittal family started the Satya Bharti School, with a commitment of Rs 200 crore.

The curriculum places special emphasis on English and computer learning. These schools also have playgrounds, sports equipment for cricket and football, and well-stocked libraries to provide holistic development to the children.

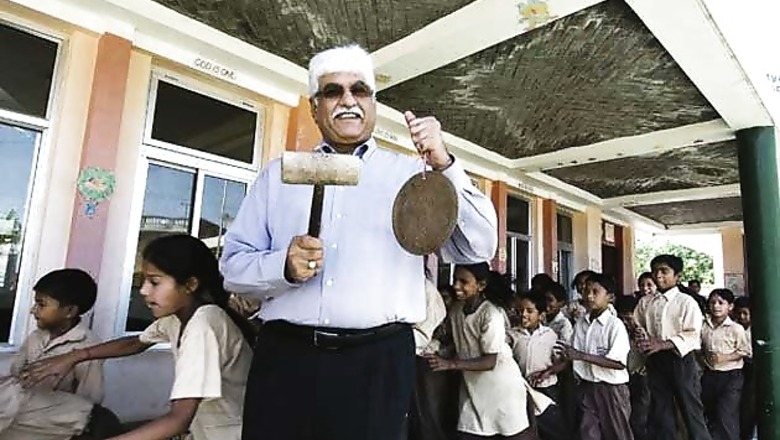

Bharti’s schools have had a positive impact on government schools too. In some villages in Punjab, when Bharti started its school and enrolment increased, the district education officer began asking government schools why their enrolments were low. Antony N.J., state head, says, inspired by Bharti, government schools in Sherpur Kalan installed sports equipment for children on their own initiative. In many areas in Sangrur and Ludhiana, government school teachers dropped by at the Bharti school to see how the children were taught. “There is an induction effect. These schools have motivated our government schools to perform,” says Lalit K. Pawar, principal education secretary, Rajasthan government.

That both models have achieved results is clear.

One state where APF’s competency based assessment has been received well is Uttarakhand. APF has been working with the state government since 2005. In this time it has trained over 1,800 teachers in competency-based assessment. Each class (from I-IV) showed an improvement of between 6 and 10 percent in scores in 2007 over 2006. From this year the government of Uttarakhand has replaced annual examinations in the state for classes I-VIII with the competency-based system.

Over in Punjab and Rajasthan, Bharti’s efforts too are beginning to pay off. Hardayal Singh, 37, sends three of his kids to a Satya Bharti School in Punjab. Earlier they used to go to government schools. “There was no teaching even if the teachers came. Kids just fooled around,” he says. It is different now. The kids try to speak in English. Their academic results have improved. And they have become conscious about hygiene at home. “I am very satisfied,” he says.

Making it work

It is equally clear that scaling up either model and keeping it going has its own set of challenges.

Both organisations have been careful about concentrating their efforts in a few states and starting in geographies they understand well. So Bharti has remained concentrated in the North, while APF started its initiative in Karnataka before taking it to other states.

Both have also been careful to not be seen as organisations with unlimited funds. As APF discovered, state governments think it has enormous funds, and expect it to bear a disproportionate share of the programme cost. “Our philosophy is that we will not invest even 1 rupee if it does not have a future implication,” says Dileep Ranjekar, CEO, APF. APF can fund it for a definite period if the government promises to institutionalise the budget. “We cannot do it indefinitely. Otherwise I am just creating a bubble and the moment APF is not there the programme goes away,” says Ranjekar. So APF shares half the cost of the programme in the beginning and then slowly reduces it, till the government bears the cost eventually.

Nevertheless, both will have to contend with one big issue: Sustainability of funds. Business will go through its ups and downs, so how do you insure against that? While the present generation supports the initiative heartily, who knows if the future generation will be interested and passionate about it?

APF is heavily dependent on Premji, its chief sponsor, for funding. Premji’s elder son, Rishad, is an APF board member along with both his parents. Although no details are available at the moment, people close to Premji say that he has thought about this long and hard and has a plan that will ensure that APF’s work will have sustainable funding.

While Premji has set aside about Rs 575 crore of stocks to fund APF’s work, Bharti is doing it through a web of initiatives, diversifying its funding base. The Mittal family, group companies, employees -- all contribute the funds. Bharti Foundation is also building an ecosystem of sponsors and partnerships to keep the fund pipeline full. Luxor provides free stationery, IBM is giving away computers. Many like Deutsche Bank, which was opening its branch in Ludhiana, decided to sponsor two schools in the city. Duraline India, a supplier to Bharti group, is giving Rs. 10 lakh in three-four tranches. “We couldn’t have done it on our own, but we can support from the outside,” says Mahendar Gambhir, senior director, Duraline India.

In Bharti’s case, one question that bothers observers is whether it will continue to find teachers. Perhaps that’s why Bharti trimmed its target of 1,000 primary schools to 500. It has now decided to also set up 50 senior secondary schools with a focus on vocational training. “We realised that our children passing out from Bharti schools needed to go somewhere,” says Rakesh Mittal.

“Scalability brings problems of quality,” says education consultant Abha Adams. Add to it the attrition rate of around 15 percent. Says Vijay Chadda, CEO, Bharti Foundation: “Attrition is a reality we have to live with. We are here to [also] energise the government system. Our teachers become the change agents when they quit.” Bharti is working hard to get better in training a large number of teachers at a minimal cost.

That’s a concern Premji echoes: “The real bottleneck today is not money -- either for us or the government, nor for some of the deeply committed NGOs that work in this space. The primary issue is shortage of talent in the education sector. This is why we are starting [a] University -- to help create a cadre of capable and committed education sector professionals.” The university, which will be operational from July 2011, will offer graduate and postgraduate degrees to those looking to make a career in education.

Where Bharti’s efforts in finding the best teachers, curriculum and pedagogy were crucial to its early success, APF’s success hinged on the way it works with the government. Its approach is not to tell the government how it should do its job or seek policy change. Instead, it is positioned as a partner that helps implement government policies.

“We do not go with fixed notions. We ask them where they want our help,” says Behar. It works closely with the government and invests a lot of time to build relationships. But frequent transfers create problems as the new officers do not always share the same equation. In Madhya Pradesh, it withdrew from the state after signing the MoU because of frequent transfers of officials. “A lot of our energy goes in establishing the relationships with state education department people. Last minute transfers hold the programme to ransom,” says Giridhar.

A convergence of ideas

Perhaps that’s why APF is now debating setting up its own schools. The idea is to demonstrate best practices in a good classroom and not suggest an alternative to government schools. The student strength will not be more than 200 in each school, and APF will spend the same that the government spends on each school. “There is a need and space for working with existing institutions, as there is need and space for creating new institutions. It’s not as though one of the methods is right and the other wrong. If there is a desire to contribute to real social change, working with the government is the only way…. You can work with the government by “working with” existing institutions or creating new ones,” says Premji.

Bharti’s strategy too has evolved. Increasingly, it has begun to collaborate with the government more closely. This is happening at a time when state governments like Punjab and Rajasthan are increasingly open to working with public-private partnership (PPP) models to manage government schools.

In Rajasthan, Bharti has taken over 49 schools along with its students but not the teachers and has re-staffed and refurbished them to run on Bharti lines. In the next stage, it has begun adopting secondary government schools along with the teachers. The government will take care of the basics while Bharti will overlay it with its own teaching methods and benchmarks. “It will be a challenge but we would bring the best practices and work within the system to improve it,” says Rakesh Mittal.

In Punjab, it is setting up new schools under a PPP model where the government gives the land, 50 percent of the capex and 70 percent of the cost of running the school. As a strategy, at the secondary level, Bharti will set up schools only in partnership with the government. The vision is to have 550 schools with 2 lakh children and around 15,000 students passing class XII every year. Beyond that, “we want to use our experience and work from the outside with the government schools,” Rakesh Mittal adds.

With experience, perhaps both APF and Bharti now realise that a multi-pronged strategy is crucial for anybody attempting to balance both scale and quality in fixing school education in India. As Vimala Ramchandran, managing director, ERU Consultants (earlier known as Educational Resource Unit), says, “India is a very vast country and requires different strategies. Karnataka is very different than Bihar.”

Making Enterprise Systems Work

Diesel Founder Renzo Rosso Knows What Matters In Fashion

Taxing by Hook or Crook

Comments

0 comment