views

Rishi Kapoor was a revolutionary. Not of the Leninist or Maoist variety, who roam the dense jungles of India and strike fear in the people and police with their menacing guns and their heavy bandoliers. Rishi was a revolutionary of Love. He embodied, in his taboo-breaking Bobby, the freedoms of Woodstock and the yuppification of renegade hippies. The youth had announced a worldwide revolt in 1968, from Berkeley to Paris to Bombay. India, still rigidly socialist and cleaving to five-year plans, was in the grip of a Nehruvian Congress that was splintering. Indira Gandhi was on the ascendant.

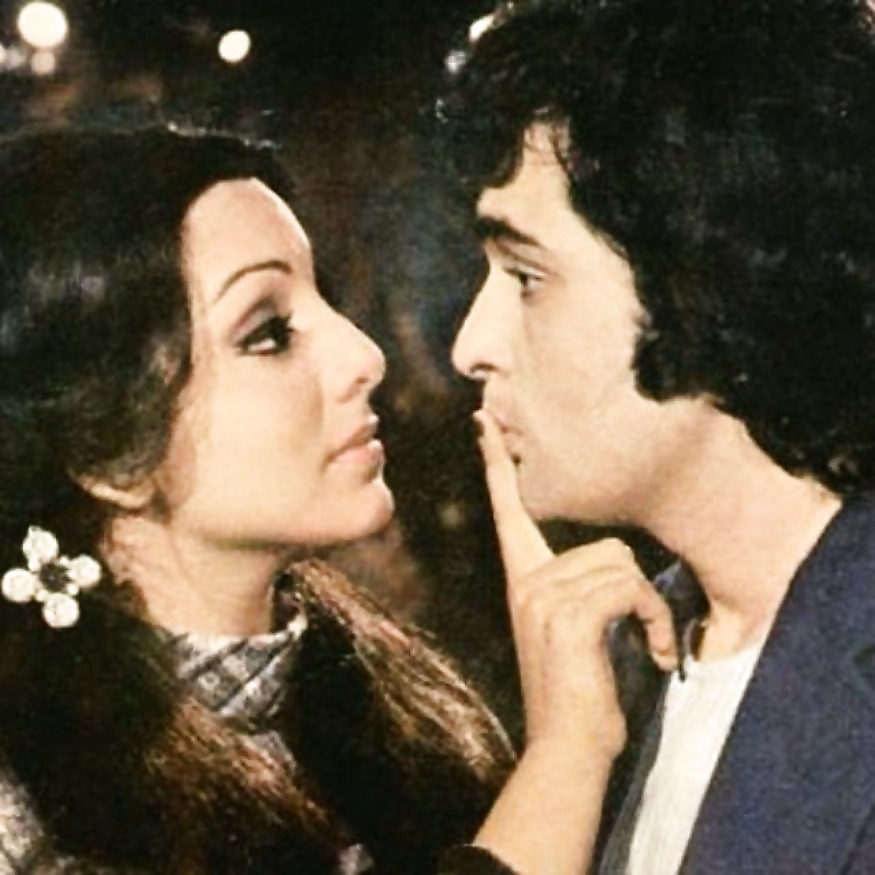

It was in 1970, Rishi’s father, Bollywood’s original showman Raj, lifted the curtains on his most personal film, Mera Naam Joker. Raj’s tramp, weary and fatigued, had fallen into a supremely existential funk. All his energy had dissipated, all his gallivanting had stopped, all his insouciance had disappeared. The tramp, which Raj Kapoor played with pathos, probably was having a breakdown and was on the verge of a collapse. Raj’s genius, which was undergirded by his innate optimism in the India Story, was to introduce a shy and extremely reserved Holden Caulfield into his sad, broken story of alienation and loneliness. This Salingeresque twist, which was enacted by a very young and chubby-cheeked Rishi, carried a whiff of revolt. His shackled prurience gets a bit loosened when he sees his teacher bathing in the buff. Rishi’s Holden did not become an outright revolutionary, but he surely got a scent of revolution. The rebellion that was triggered by the clamorous youth, who were sick of a sclerotic society that didn’t give them their rightful due.

The Holden who stepped out of the fading frame of Mera Naam Joker became a full-fledged Caulfield in Bobby. He wasn’t a catcher in the rye; he was neither a catcher on the sly. He was a catcher, but certainly not shy. Rishi Kapoor had announced to the world that he was India’s answer to James Dean, his rebellion a bit tame but still powerful for an India, which chained to hoary conventions and strange taboos was gasping for air.

He was a rebel, with a serious cause. He was a chocolate boy gone rogue. He was a dancing, exuberant Camus to his grim, existential Sartresque father. He was out of the clutches of absurdity and ready to embrace a new future. He made the screen sizzle in 1973. Inside the theatre, everyone was wonderstruck. Outside, India, after going to war with Pakistan for the third time, was facing its own student revolts.

Rishi was a good foil to a simmering Amitabh Bachchan, who symbolised, with his pursed lips and silent, sullen looks, an India on the boil. An India that was going the full Sartrean arc from Nehru’s Being to Indira’s Nothingness. An India beset with absurdity and plagued by existential doubts. An India weighed down by its rotten, soul-killing systems. An India where the Ambedkarean topsoil of democracy was fast being gouged out to expose the turbulence within. Being was swiftly turning into nothingness. Rishi’s Caulfield was an act of revenge on the system. Like Camus, he broke with the perils of stubborn absurdity and embraced a humanism that encouraged rebellion but kept the faith.

India entered a dark age in 1975 and Bachchan continued to blow his fuse. As he, with his heavy blows and belligerence, kept striking the stalled and corrupt system and became a messiah, Rishi, like a content Everyman, continued to spread the gospel of love.

Bachchan yelled, Rishi yearned. Bachchan craved his own lore, Rishi wanted his own love. Manmohan Desai, with his uncanny eye for box-office success, brought the two together in Amar Akbar Anthony. The Muslim Akbar went to Rishi; the Christian Anthony went to Bachchan. And the Hindu Amar went to Vinod Khanna. Bachchan raged here too, but with some booze-fuelled self-pity.

Rishi, a flirtatious tailor, yearned and romanced his heart out. Khanna neither raged nor yearned. He was the most solid and respected (being a policeman) among the three. The casting was Desai’s Bollywood brilliance at work. Rishi made Bachchan more humane and prone to doubts. They would, of course, act together in more films in the coming years, with Bachchan getting more and more mellowed in his joyously buoyant company.

When the gagging of India’s freedoms was lifted, the country had truckloads of pent-up energy to release. Rock and roll burst into the scene, with RD Burman dexterously beating his conga drums and Rishi Kapoor bouncily singing his disco songs. It was a controlled explosion of cacophony to snuff out the resentments and rages left by India’s dark ages.

Holden Caulfield had no qualms in turning himself into a slim Elvis Presley, jiving and crooning his way to our hearts. Mithun too debuted around the same time, but the appellation of India’s heartthrob was reserved for Rishi. The song and dance continued for some years. Om Shanti Om became a soothing national anthem. It calmed anxieties and made people gyrate their resentments away. Rishi faced tough competition from foreign bands like BoneyM and Abba, but he stood his ground. India was his haseena and he was its eternal deewana.

Yash Chopra, who brought bling and chiffon beauty to India, took Rishi and Sridevi to Switzerland to romance and dance. Just a few years before India’s liberalisation, Chopra was trying to show us what the possibilities of globalisation entailed. Rocking and shaking among the tulips of Switzerland, Rishi, along with Sridevi, showed India what was coming in the next years. The Bobby boy of 1973 had grown mature as Chandni’s man in 1989, but the tag of the rebel out to cross new frontiers stayed with him.

Rishi had put on weight and the years showed on him, but his rebellion—the Everyman’s quest to stand up and be counted—had not died. It was still alive and kicking in both India and Switzerland. Bachchan had faded, his angry man persona in tatters, but Rishi was still gung-ho and all ready to welcome India’s go-go years.

When Manmohan Singh, in 1991, proudly announced to the world that India’s time had come, Rishi, the Holden Caulfield who had grown a tad bulky with the burden of so many expectations, would have chuckled to himself. Two years ago, in 1989, he had taken India on a Swiss jaunt and already shown that our time was coming fast. It was not the Karan Johar hero who brought the shining world into our consciousness; it was Rishi. And he had started that journey in Bobby, on his mini Rajdoot, a bike that became a national dream. And he kept on spinning more and more dreams for us. These were not Borgesian, labyrinthine voyages; these were simple, uncomplicated travels done just to fulfil own dreams. This was a sated Holden Caulfield travelling Route 66; this wasn’t an angsty Caulfield looking into the back of beyond for nirvana.

Salinger, because for his mania for privacy and not publishing, did not give his Holden a second chance. Rishi’s Holden did get a second innings in a Bollywood that was changing and wasn’t worshipful of Kapoors, the first family of Bombay cinema. Rishi became a mafia don, played Dawood, and even was sent to Banaras to play an aggrieved Muslim. It was as if the Akbar of Desai’s film had grown old and was trying to fend for himself. There were severe assaults on his dignity, but in Mulk he showed he still had some fight left in him.

He did not want the world to see him as a dotard; he still wanted to see him as a dogged deliverer. A deliverer of faith, freedom and fineness. He was a Sisyphus who never flinched from rolling his stone up; he was the Prometheus who gave fire to many ideas, but always remained chained to his ideal of work. The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy, said Camus. To which Rishi, with that sly smile of his, would have replied: I rebel; therefore I exist.

Comments

0 comment