views

William Dalrymple is a tricky person. His history doesn’t always complement his politics. His books, though often appearing to be an apologia for the decadent and depraved later Mughals, have at least been a damning exposé on the sorry state of history writing in India. That a history book should be written like a novel with rigorous research put in the endeavour. Stories should remain the core of the book and not a farfetched ideological fantasy dictated by what was once the “Only Fatherland” of progressive ideas.

Even when Dalrymple is not delving into history and wears the hat of a contemporary chronicler, he still seems to tread a fine line of not invading the sacred in his search for modern India. In Nine Lives (2009), for instance, he recounts with empathy the story of “The Dancer of Kannur”, in which Hari Das, a Dalit from Kerala, is a “part-time prison warden for 10 months of the year”, but during the Theyyam dancing season between January and March, he is “transformed into an omnipotent deity” to be worshipped even by the high-caste Brahmins. Then there are the stories of an MBA sannyasin, Ajay Kumar Jha, and an idol maker, Srikanda Stpathy, Tamil Nadu’s Swamimalai town, told with warmth and understanding.

The politics of Dalrymple, however, is starkly different — and dangerous. It undoes almost everything he builds as a historian, though one can find traces of self-contradiction in his books too. In Nine Lives, for instance, his reverence for the sacred appears hollow and pretentious as he invokes Romila Thapar’s idea of “syndicated Hinduism” to intellectually discredit Hindu resurgence in India. Dalrymple, quite mischievously, calls it “Rama-fication of Hinduism”.

This two-faced nature of Dalrymple — to project his reverential aspect of the sacred while simultaneously working to dismantle it — was evident early this week when he, in an interview with a British daily, questioned the idea of British-looted treasures being returned to India. He wanted the wealth that the British had illegally drained out of India — a phenomenon he himself exposed in his book The Anarchy (2019), pushing the country’s share in world economy from 23 percent in the early 18th century to 3 percent in 1947 — to stay put in the island nation. Now that’s the typical Dalrymple way of having the cake and eating it too. He takes the moral high ground by exposing the British plunder, and then like a blue-blood British he vetoes the transfer of that looted wealth to the country of its origins.

According to Dalrymple, Mughal treasures looted by the British might never be displayed if they are returned to India, which is currently run by “a Hindu nationalist government that does not display Mughal items”. He, thus, recommends keeping the loot in Britain. “You can go to Delhi and not see a display, at the moment, of Mughal art at all. But it’s there, beautifully displayed, in the British Library, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum.”

This is classic white supremacist syndrome with a post-colonial twist: In their heydays of colonialism, the Europeans justified their loot in the name of “civilising the savage”. The truth, however, was just the opposite: When they first reached Akbar’s court, the Mughal ruler thought of civilising these European immigrants, whom he called “an assemblage of savages”. Dalrymple himself writes in The Anarchy how in the 17th-18th centuries, British shopkeepers passed off shoddy English-manufactured textiles as Indian in order to gain greater profits.

Ironically, Dalrymple, who today wants the stolen artefacts to remain in Britain museums, has taken a starkly different position in his book, The Anarchy, as he lists out the looting of thousands of priceless objects from India to Britain by the employees of the East India Company. “The Company’s conquest of India almost certainly remains the supreme act of corporate violence in world history,” he writes. Earlier, in an interview with the Smithsonian magazine in 2017, he had emphasised the need for the return. “If you ask anybody what should happen to Jewish art stolen by the Nazis, everyone would say of course they’ve got to be given back to their owners. And yet we’ve come to not say the same thing about Indian loot taken hundreds of years earlier, also at the point of a gun,” he said matter-of-factly.

So, what has changed from 2017 to 2023? Nothing exactly! Even the government in power remains the same. The only thing that has changed in the past five years is the growing global clout of India. Today, as India has displaced Britain to become the fifth-largest economy in the world, and is set to take the third slot ahead of Japan and Germany by the end of the decade, Indians have never been so steadfast and vocal about getting their stolen heritage back. It’s no longer about Western benefaction; it’s about a new India seeking its rightful legacy.

Dalrymple’s hoax is further called when one analyses his claim of Mughal treasures being looted by the British. No, Mr Dalrymple, the British looted India’s treasures, not Mughals. Babur didn’t bring any of these treasures from Samarkand or Kabul. He invaded India precisely because it was a wealthy territory, despite pervading political chaos in the subcontinent. But, for the sake of argument, let’s analyse what was typically Mughal. Kohinoor, for instance, has a south Indian connection. According to the diary of Alauddin Khilji (1296-1316) of the Delhi Sultanate, he looted it from the Kakatiyas.

There are many such non-Mughal objects and artefacts: The British Museum currently hosts a bronze Nataraja sculpture belonging to the Chola era (c. 1100 AD), a granite sculpture of Shiva and his wife Parvati from Odisha (c. 1100-1300 AD), and a carved granite figure of Nandi from the Deccan (c. 1500s AD). This museum also has a marble statue of Goddess Saraswati (c. 1034 AD), originally from the Bhojshala Temple in Madhya Pradesh, and a two-sided limestone relief from Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, carved first in the 1st century BC. Also, if you thought there were just one diamond called Kohinoor, you would be wrong: For, Britain looted another one soon after the Anglo-Maratha war in 1818; called the Nassak Diamond, it was a large diamond originally weighing 89 carat, and adorning the eye of the main idol in Trimbakeshwar Shiva Temple, near Nashik, Maharashtra. The list of looted heritage is long and exhausting.

DV Tahmankar, in his book The Ranee of Jhansi (1958), while detailing the loot of Jhansi in 1858, writes how the British took away jewellery, gold, silver and other valuable stuff. By the end of the pillage, he writes, “Not a single useful thing was left with the people.” This scene was repeated in one state after another. In fact, one can understand the never-ending plundering appetite of the British from the fact that one of its ‘reformist’ Governor Generals, Lord Bentinck, in the 1830s, had worked out plans to dismantle the Taj Mahal and ship the marbles to collectors in London. Today, the Taj stands in Agra in all its glory just because the auction was a failure and the British authorities thought it was not worth demolishing the monument!

Dalrymple should realise that India is not seeking the damages of wealth Britain had drained out of the country, which as per one estimate amounts to $45 trillion. It just wants its heritage back. And that heritage is India’s, and not that of the Mughals, howsoever hard Dalrymple would want us to believe otherwise.

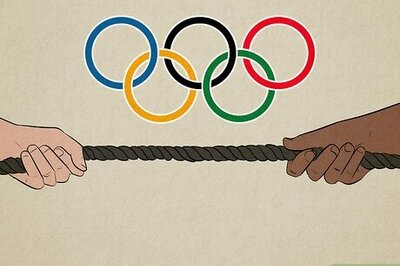

In one of his interactions with this author almost a decade ago, Dalrymple proudly talked about having Mughal blood in his veins. Maybe it is this blood that stops him from appreciating the new India story. His elitism makes him suspect the democratisation, even if partly, of the Lutyens ecosystem. Or, maybe his uneasiness comes from the fact that the new, modern India is fast shedding its colonial inhibitions and is no longer shy of its civilisational roots — an India that has stopped looking Westward for legitimacy, vindication. For, Dalrymple could become a literary phenomenon precisely because he first landed in India that was old, docile and down with colonial hangover. Time is ripe for the ‘White Mughal’ to stop running with the Indian hare and hunting with the British hounds.

The author is Opinion Editor, Firstpost and News18. He tweets from @Utpal_Kumar1. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

0 comment