views

For anybody who has an enduring interest in India’s political developments, the Gujarat Assembly election results will stand out as a fascinating case study. While the headlines say the BJP has won 99 seats, 16 less seats from its 2012 tally of 115, the Congress managed 77, a gain of 16 seats from its 2012 count of 61.

The dominant interpretation of these numbers follows a predictable line — the BJP has lost significant ground and the Congress has gained sharply, so much so that some analysts have termed it a major scare for the BJP. This would be a very binary yes or no diagnosis of the results. It is an oversimplified analysis of India’s diverse and complex polity. It is akin to drawing a conclusion that coffee has become cheaper because there is a crop failure in a certain tea estate.

The Congress party and its President Rahul Gandhi’s spin masters continue to belabour on how the Gujarat elections mark a point of inflection in India’s recent political history. The results, according to this line of analysis, mark the emergence of Gandhi as credible challenger to the BJP, strong enough to stop the BJP’s juggernaut led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and its President Amit Shah.

Data, however, suggests such a line of argument is not only riddled with glaring fallacies, but also mischievous and peppered with a liberal dose of malice. The Assembly election results suggest that the BJP has not only retained its base, but also made some significant inroads into traditional Congress bastions such as tribal pockets of Gujarat.

The importance of anti-incumbency in India’s electoral politics cannot be ignored. It often, but not always, gives an edge to the opposition and challenger to the incumbent. This is one primary reason why power changes hands alternately every 5 years in most state elections.

Yet, it would be grossly erroneous to overemphasize the factor in swinging elections. The BJP has successfully, and through a people-focused development model, consistently defied this thumb rule. For instance, it has returned to power in Gujarat for the sixth time and three times in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

Now let’s look at the numbers. In the 2017 Assembly polls, the BJP clocked 49.1% votes — an increase of 1.25 percentage points over its 2012 performance. Importantly, this was BJP’s best performance since 2002, when it returned with 49.85% vote share. The BJP’s vote share in 2017 show that one in every two persons voted for them — despite a strong anti-incumbency factor after 22 years of ruling — a remarkable achievement measured by any metric of psephology and politics.

On the other hand, the Congress has come home with its best performance since the 1985 Assembly election in Gujarat, by polling 41.4% vote. However, is it good enough for the Congress to gain a few votes but lose the election? As a matter of fact, the Gujarat performance should worry Congress, because it rode on its lesser known alliance partners, to consolidate the anti-BJP votes. The 2.5% increase in Congress’s vote share has mainly come from its supporters and Independents, whose vote share has plummeted to 9.5% in 2017 from 13.2% in 2012. Moreover, Congress is still 7.7% votes behind the BJP, which is a significant gap in a state characterized by a pronounced bipolar polity.

In a normal zero-sum game election, the gap of 7.7% votes should have given at least a two- thirds majority to the BJP. Instead, the BJP’s tally stopped at just 99 seats. The main reason behind this anomaly is huge victory margins for the BJP in many seats.

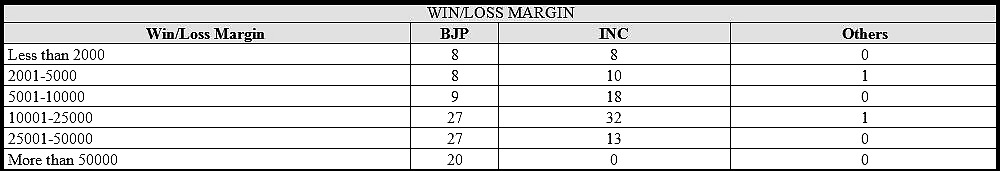

Consider the following statistics which clearly show that as victory margins go up, BJP’s strike rate too goes up. For instance, BJP won 20 seats by a margin of over 50,000 votes while Congress failed to manage such a margin even in one seat. The Congress has won more seats with lesser margins.

As far as regional variations in terms of votes are concerned, the BJP is way ahead of the Congress in South, East and Central Gujarat while Congress inched ahead in the North and Saurashtra.

When we look at conversion of seats, BJP has more or less retained its seats in all regions except in Saurashtra, where it has suffered a loss of 13 seats, which it now appears, was the single most important reason in its final tally dropping to double-digits.

Therefore, it can be safely presumed that the factors behind a reduced tally of the BJP were localized in Saurashtra. One can also debate whether it happened due to farmer distress or the Patel vote splitting due to the Patidar agitation or malicious caste-based narratives unleashed by the Congress.

The results of 30 rural Assembly constituencies in the Rural Saurashtra and Kutch Region further demolish the myth of Rahul Gandhi and Congress’s resurgence.

This is the cluster of seats where Keshubhai Patel’s GPP had polled 10% votes winning two seats in 2012. Still, the BJP managed to win 18 seats, well ahead of Congress’s tally of 9 seats. For the purpose of analysis, one can assume that a section of voters in this region is not hard core BJP supporter and is vulnerable to its personal interests, a factor that worked for Keshu Bhai in 2012.

However, this split could not significantly dent BJP’s prospects in 2012 because these voters didn’t align with any significant block of voters.

In this election, Congress registered a gain of 12% votes in this area while others went down by a significant 12%. Therefore, it is likely that the heavy gains for Congress came from the same section of voters who went to Keshu Bhai’s GPP in 2012. But unlike in 2012, this split has made a huge dent on BJP’s tally this time because it was added into Congress’ base vote. As a result, Congress swept the region, winning 24 of 30 seats and the BJP went down to just five.

Thus, gains for Congress were not due to any pro-Congress or anti-BJP sentiments across Gujarat but due to local factors concentrated in 30 seats of rural Saurashtra. Therefore, if Rahul Gandhi and Congress party had so much of traction, as the case is being made, then why was it limited to just 30 seats in rural Saurashtra.

Historically, Congress has been doing well in the rural pockets of Gujarat. The state has 101 Assembly segments with less than 30% urban population largely having a rural character.

Even in this rural belt, the BJP has made a gain of 1 percentage point votes over 2012 by polling 44.5%, marginally lower than the Congress’s 45.9% vote share. This marginal lead converted into 63 wins for the Congress and its allies while BJP could win just 36 seats, which ultimately made the difference.

It is also important to keep in mind that as many as 21 seats were decided by very narrow margins in favour of the Congress as it won seven seats by less than 1% and 14 seats by 1% to 5% vote margin. Thus, considering its historical weakness in rural pockets, BJP’s performance is not irreconcilable, although it has to be mindful of the fact that a united opposition can pose a challenge if agrarian concerns are not addressed.

The performance in tribal dominated areas is another way to understand popularity of a party amongst marginalized sections of the society. Gujarat has total of 14% tribal population and 31 consistencies where tribes account for more than 30% electoral.

These 31 segments are a good indicator of the tribal mood. BJP was slightly behind Congress in this area in 2012 as they had polled 42.9% and 43.8% votes respectively. In 2017, BJPs’ vote share jumped to 47.4%, cantering past Congress’s 44.5% by 2.9 percentage points. Even an alliance with BTP, a tribal outfit led by JD(U) rebel Chhotibhai Vasava couldn’t help Congress retain supremacy in this stronghold pocket. Though in terms of seats, both Congress and BJP retained its 2012 tally by winning 16 and 14 seats each.

Therefore, even if we presume that BJP suffered losses amongst Patels, it compensated this loss by gaining tribal votes that helped it to not only retain but increase its vote share.

While Congress may find it hard to retain the new-found support of a section of Patels because they are a politically pragmatic community and would like to be identified with the ruling disposition. BJP leadership understands the vulnerability of this section of Patels’ new found love for the Congress. Probably this is the reason that in his victory address on December 18, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had said that all those who drifted away from the BJP due to a malicious campaign by the opposition should return home because BJP believes in “Sabka Sath Sabka Vikas”.

On the other hand, BJP will not have difficulty in retaining its gains in the tribal pockets because of its aggressive tribal, Dalit and poor outreach. Moreover, due to not so effective leadership and lack of government power, Congress does not have the ability to woo back its long time core constituency.

Thus, a careful micro analysis suggests that marginal gains for the Congress may not be sustainable because it is localized in one small pocket of Gujarat and have occurred due to personalized caste-based campaign instead of any pull factor. With focused efforts, BJP can easily regain lost ground and emerge strongly in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

Author is a Psephologist and a member of BJP. Views are personal.

Comments

0 comment