views

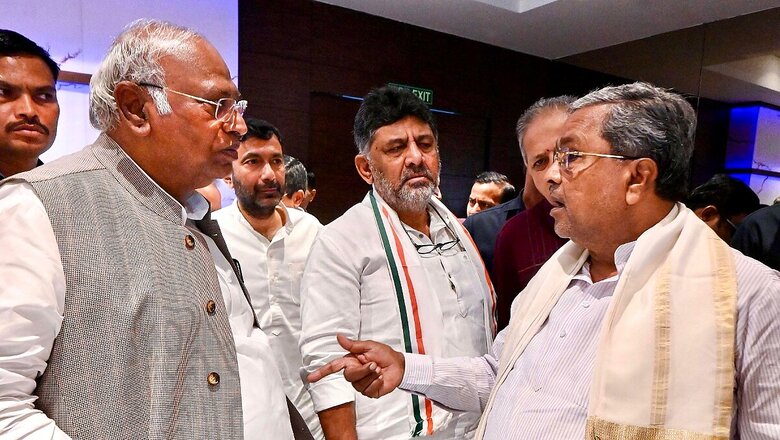

In the aftermath of severe backlash, the Siddaramaiah government has tossed the bill mandating reservations for Kannadigas in the private sector in cold storage. Two major themes underlie the rather sudden introduction of this bill. The first is purely political.

In 2023, the Congress seized power in Karnataka with a majority that it notched up by reckless promises of an impossible range of freebies. After a year of being in power, it has nearly bankrupted the state. And then there is the concomitant inevitability that accompanies a Congress regime — rampant, unchecked and pervasive corruption.

Two recent corruption scandals have erupted in quick succession. The first was the candid loot of the state’s treasury in a manner of speaking. It involved a brazen diversion of taxpayer money allocated to the Valmiki community. Among other things, it was used to procure colossal amounts of liquor to be distributed during elections. Those involved in the scam also funnelled some of this ill-gotten cash to buy high-end cars and other luxury items. The Enforcement Directorate has arrested the minister in charge.

The second scandal has directly bombed Siddaramaiah’s own electoral backyard: Mysore. This involves gross irregularities related to land allotments done by the Mysore Urban Development Authority (MUDA). Among other allegations, this scam points fingers directly at the chief minister’s wife and other family members.

And so, the news doing rounds in the capital is that the aforementioned reservations bill was introduced to deflect attention from these high-profile scams.

The second theme requires a slightly detailed examination.

The demand for mandatory reservations for Kannadigas in the private sector has a history of two-and-a-half decades. It is also a vile progeny of several toxic and fractious ideologies that have plagued large parts of India for more than a century.

The first vocal demand for such linguistic reservations surfaced during the tenure of Chief Minister S.M. Krishna (1999-2004) who was then hailed as the leader who transformed Bangalore as the IT hub and Silicon Valley of India. That was roughly the period when Bangalore witnessed a record influx of migrants, which eventually altered its character to an unrecognisable extent.

Back then, the lobby agitating for mandatory reservations for Kannadigas in the private sector had mainly trained its guns against Infosys, the poster boy of India’s IT revolution. A major reason for this selective targeting was the fact that its founders, including Narayana Murthy and Sudha Murthy, were thoroughbred Kannadigas who had shot to this level of eminence and entrepreneurial success, which was even beyond the realm of dreams in the preceding decade.

On the anvil of the 2010 decade, the aforementioned lobby had acquired greater power. It is in advisory positions with the present establishment. Those acquainted with the realities in the state will testify as to how this lobby comprises a bizarre amalgam of language chauvinists, sun-dried communists and social justice “warriors”.

The two chief ministerial terms of Siddaramaiah show that he is perhaps the only chief minister of Karnataka whose policies are directly derived from a 1960s communist user manual. In fact, he is the most (Left) ideological chief minister to ever rule the state. Freebies, flagrant appeasement of Muslims, splitting the Hindu community, and open patronage of Far-Left litterateurs and writers are some hallmarks of his administration.

However, the aforementioned reservation bill is quite a different creature. It is the culmination of decadal activism and also a rather peculiar outcome of history, geography and demography.

Karnataka’s geography can be broadly divided into the Old Mysore Region, Northern Karnataka, Malenadu and Coastal Karnataka, each exhibiting certain distinctive character traits. While the Kannada language unites the state and there have been historical movements to strengthen and reform the language, linguistic chauvinism arose primarily in Bangalore and its adjoining areas.

A major reason for this is the queer situation of Bangalore which is both the state’s political capital and financial hub. Without going into details, Bangalore was never meant to be this. The original Bangalore — even of the 1950s — was a neat little pocket surrounded and nurtured by a vast ecosystem of villages and lakes, all of which have now become grotesque residential colonies cum commercial centres.

Liberalisation and the IT boom brought in both a rush of migrants and money with the result that Kannadigas in Bangalore became a minority. There was another phenomenon — the outward migration of at least two generations of Bangalore-born Kannadigas to America. These, coupled with several allied factors made the situation ripe for fanning linguistic chauvinism. These reasons are also why we don’t notice this kind of chauvinism in other regions of Karnataka.

On the philosophical plane, chauvinism is a weaker child of fanaticism and insecurity is the father of fanaticism. However, it is endowed with considerable capacity to capture and retain political power in electoral democracies.

Tamil Nadu is the only state where Tamil linguistic chauvinism succeeded in capturing and monopolising political power. It was the sibling of the more toxic and destructive Dravidian ideology. Both Dravidianism and Tamil chauvinism were premised on Brahmin hatred. For several decades, even Maharashtra, under Bal Thackeray, dallied both with linguistic and identity chauvinism (the Marathi maanoos narrative) but reaped paltry dividends in the long run.

More than a century ago, some political forces in the Old Mysore region chose to embrace this brand of Tamil linguistic chauvinism and tried to tailor it to suit their own needs. However, they failed spectacularly and eventually merged with the Indian National Congress. And a century later, the inheritors of the same forces have made huge inroads in the same Congress. The withdrawn reservation bill of Siddaramaiah is the outcome of this inroad.

Back then, their agitation had costed a luminary of Sir M. Visvesvaraya’s stature his Diwan’s chair. It is best to read the full story in his own words, recorded in Memoirs of My Working Life: “About the years 1916-17, there was an agitation in Madras against the Brahmin community in view of the predominant position they enjoyed in Government services. This agitation spread to Mysore also. I was aware that non-Brahmin communities were backward on account of lack of higher education. The education problem had been vigorously attacked ever since I came to Mysore. I had arranged for the Mysore Government granting liberal scholarships to backward communities and depressed classes to encourage their education.”

Visvesvaraya wrote, “Special steps were also taken to advance the prospects of members of backward communities in Government service. It was true that there was considerable inequality in preferment to offices and the Brahmin community had worked their way to the front.”

He continued, “The policy adopted of spreading education rapidly was showing some results. As stated before, the school-going population had been nearly trebled. There was a desire in some quarters to hold back the [Brahmin] community by restricting their admission to educational institutions and otherwise reducing their opportunities for acquiring education. With this aim, it was impossible to sympathise because it was an attempt to put back a section of the population which by its own special enterprise was going forward.”

Visvesvaraya added, “There was a definite proposal put forward by several leading members of the non-Brahmin community in Mysore to adopt the policy of the non-Brahmin leaders and their Press in Madras.”

Which was when Leslie Miller, the chief judge of Mysore played truant. He spotted the perfect opportunity to unseat Visvesvarayya and deepen the wedge between Brahmins and non-Brahmins. Sadly, he triumphed. But then, this was Visvesvarayya’s vision: “My idea was that by spreading education rapidly and adopting precision methods in production and industry, the State and its entire population would progress faster. By ignoring merit and capacity I feared production would be hampered and the efficiency of the administration, for which we had been working so hard, would suffer. There was never any complaint that I favoured any particular community in making appointments.”

He added, “His Highness the Maharaja seemed anxious to placate the backward communities and the leaders in the State who supported the policy advocated by the non-Brahmin leaders of Madras.”

The distinguished Diwan resigned.

This slice of history offers a profound lesson. Siddaramaiah’s withdrawn reservation bill is a continuum of that century-old episode. In that period, reservations were restricted only to one umbrella group: non-Brahmins.

It’s a melancholic but familiar story.

Ever since, reservations have been weaponised to the extent that it is now almost impossible to count the religious, sectarian, and social groups, sub-groups and micro-groups to which reservation has been extended. One of the most brilliant expositions of this topic is Arun Shourie’s aptly titled book, Falling Over Backwards. Indeed, the journalist, litterateur and statesman, D.V. Gundappa had pretty much predicted that the present state of affairs would ensue in Karnataka way back in 1930 when he wrote this in an editorial: “To the noble sentiment of uplifting the backward sections are tied several other sentiments and principles. In the attempt to uplift the backward sections, care must be taken not to deliberately push the forward sections behind.”

But to state the blunt truth bluntly, the Karnataka government’s frozen bill rests on two foundations: language and the private sector. It stands to reason to pose two logical questions.

One, it appears that the reservation cow has been milked dry in Government jobs. And so, the private sector is fair game.

Two, by mandating language-based reservations, the Government seems to think that Kannadigas lack the capacity, skill and talent to secure jobs without the State’s intervention. This race to the bottom will cost the nation dearly.

Today, it is a taboo, almost a crime to even scrutinise the premises of reservations. On a moral plane, it is patently unjust because it denies both humanity and agency to an individual — however disadvantaged he or she might be — through state-enforced dependence. On the same plane, it corrupts the individual by engendering sloth and unaccountability.

A shoemaker’s son like Abraham Lincoln didn’t need reservations to earn eminence and thereby, a golden chapter in world history.

Postscript

As a Kannadiga who dearly loves the language, my state, its culture and its profound heritage, I find all this remarkably tragic on so many fronts.

The Mysore Wodeyars, Diwans and Deputy Commissioners had an exalted vision for transforming the state into a Model State. And they succeeded in it. They stood for and embodied grand and sublime values and ideals.

One wonders what the current establishment stands for.

The author is the founder and chief editor, The Dharma Dispatch. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment