views

New York: In several hours on Tuesday, Dr Ashley Bray performed chest compressions at Elmhurst Hospital Center on a woman in her 80s, a man in his 60s and a 38-year-old who reminded the doctor of her fiancé. All had tested positive for the coronavirus and had gone into cardiac arrest. All eventually died.

Elmhurst, a 545-bed public hospital in Queens, has begun transferring patients not suffering from coronavirus to other hospitals as it moves toward becoming dedicated entirely to the outbreak. Doctors and nurses have struggled to make do with a few dozen ventilators. Calls over a loudspeaker of “Team 700,” the code for when a patient is on the verge of death, come several times a shift. Some have died inside the emergency room while waiting for a bed.

A refrigerated truck has been stationed outside to hold the bodies of the dead. Over the past 24 hours, New York City’s public hospital system said in a statement, 13 people at Elmhurst had died.

“It’s apocalyptic,” said Bray, 27, a general medicine resident at the hospital.

Across the city, which has become the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States, hospitals are beginning to confront the kind of harrowing surge in cases that has overwhelmed health care systems in China, Italy and other countries. On Wednesday evening, New York City reported 20,011 confirmed cases and 280 deaths.

More than 3,922 coronavirus patients have been hospitalized in the city. Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Wednesday offered a glimmer of hope that social-distancing measures were starting to slow the growth in hospitalizations statewide. This week, the state’s hospitalization estimations were down markedly, from a doubling of cases every two days to every four days.

It is “almost too good to be true,” Cuomo said.

Still, hospitals are under siege. New York City’s hospitals run the gamut from prestigious teaching institutions catering to the elite to public hospitals providing care for some of the poorest communities in the nation. Regardless of whom they serve, few have been spared the impact of the pandemic: A flood of sick and fearful New Yorkers has besieged emergency rooms across the city.

Working with state and federal officials, hospitals have repeatedly expanded the portions of their buildings equipped to handle patients who had stayed home until worsening fevers and difficulty breathing forced them into emergency rooms. Elmhurst, among the hardest-hit hospitals in the city, is a prime example of the hardships medical centers and their staffs are facing across the country.

“Elmhurst is at the center of this crisis, and it’s the number one priority of our public hospital system right now,” the city’s public hospital system’s statement said. “The front line staff are going above and beyond in this crisis, and we continue surging supplies and personnel to this critical facility to keep pace with the crisis.”

Dr. Mitchell Katz, the head of the Health and Hospitals Corp., which operates New York City’s public hospitals, said plans were underway to transform many areas of the Elmhurst hospital into intensive care units for extremely sick patients.

But New York’s hospitals may be about to lose their leeway for creativity in finding spaces.

All of the more than 1,800 intensive care beds in the city are expected to be full by Friday, according to a Federal Emergency Management Agency briefing obtained by The New York Times. Patients could stay for weeks, limiting space for newly sickened people.

Cuomo said on Wednesday that he had not seen the briefing. He said he hoped that officials could quickly add units by dipping into a growing supply of ventilators, the machines that some coronavirus patients need to breathe.

The federal government is sending a 1,000-bed hospital ship to New York, although it is not scheduled to arrive until mid-April. Officials have begun erecting four 250-bed hospitals at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Midtown Manhattan, which could be ready in a week. President Donald Trump said on Wednesday on Twitter that construction was ahead of schedule, but that could not be independently confirmed.

Officials have also discussed converting hotels and arenas into temporary medical centers.

At least two city hospitals have filled up their morgues, and city officials anticipated the rest would reach capacity by the end of this week, according to the briefing. The state requested 85 refrigerated trailers from FEMA for mortuary services, along with staff, the briefing said.

A spokeswoman for the city’s office of the chief medical examiner said the briefing was inaccurate. “We have significant morgue capacity in our five citywide sites, and the ability to expand,” she said.

In interviews, doctors and nurses at hospitals across the city gave accounts of how they were being stretched.

Workers at several hospitals, including the Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx, said employees such as obstetrician-gynecologists and radiologists have been called to work in emergency wards.

At a branch of the Montefiore Medical Center, also in the Bronx, there have been one or two coronavirus-related deaths a day, or more, said Judy Sheridan-Gonzalez, a nurse. There are not always enough gurneys, so some patients sit in chairs. One patient on Sunday had been without a bed for 36 hours, she said.

At the Mount Sinai Health System, some hospital workers in Manhattan have posted photos on social media showing nurses using trash bags as protective gear. A system spokesman said she was not aware of that happening and noted the nurses had other gear below the bags. “The safety of our staff and patients has never been of greater importance, and we are taking every precaution possible to protect everyone,” she said.

With ventilators in short supply, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, one of the city’s largest systems, has begun using one machine to help multiple patients at a time, a virtually unheard-of move, a spokeswoman said.

Elmhurst Hospital Center opened in 1832 and moved to its current Queens location in 1957, making it one of the oldest hospitals in New York City.

In the neighborhood it serves, Elmhurst, more than two-thirds of residents were born outside of the United States, the highest such rate in the city. It is a safety-net hospital, serving mainly low-income patients, including many who lack primary care doctors.

Queens accounts for 32% of New York City’s confirmed coronavirus cases, more than any other borough and far more than its share of the city’s population. It also has fewer hospitals. Elmhurst is one of three major hospitals serving a large population and is centrally located, which in part explains why it is busy in normal times and even busier now.

Medical workers said they saw the first signs of the virus in early March — an increase in patients coming in with flulike symptoms before the alarm had been fully raised in the city and the country. Tests results were taking longer then, but they eventually confirmed that many of these patients had coronavirus.

In the weeks after, the emergency room began filling up, with more than 200 people at times. Every chair in the waiting room was usually taken. Patients came in faster than the hospital could add beds; earlier this week, 60 coronavirus patients had been admitted but were still in the emergency room. One man waited almost 60 hours for a bed last week, a doctor said.

The patients coming in now are sicker than before because they were advised to try to recover at home, doctors said.

Like other hospitals, Elmhurst has come perilously close to running out of ventilators several times; other hospitals have replenished its supply.

Despite the more optimistic projections by the state about hospitalization rates, the crowds outside of Elmhurst have not thinned out.

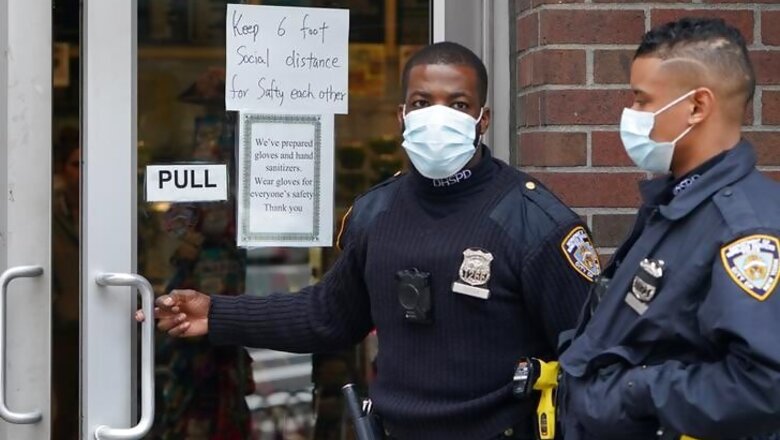

The line of people waiting outside of Elmhurst to be tested for the coronavirus forms as early as 6 a.m., and some stay there until 5 p.m. Many are told to go home without being tested.

Julio Jimenez, 35, spent six hours in the emergency room on Sunday night after running a fever while at work in a New Jersey warehouse. He returned on Monday morning to stand in the testing line in the pouring rain. On Tuesday, still coughing, eyes puffy, he stood in line for nearly seven hours and again went home untested.

“I don’t know if I have the virus,” Jimenez said. “It’s so hard. It’s not just me. It’s for many people. It’s crazy.”

Rikki Lane, a doctor who has worked at Elmhurst for more than 20 years, said the hospital had handled “the first wave of this tsunami.” She compared the scene in the emergency department with an overcrowded parking garage where physicians must move patients in and out of spots to access other patients blocked by stretchers.

Family members are not permitted inside, she said.

Lane recalled recently treating a man in his 30s whose breathing deteriorated quickly and had to be put on a ventilator. “He was in distress and panicked, I could see the terror in his eyes,” she said. “He was alone.”

Michael Rothfeld, Somini Sengupta, Joseph Goldstein and Brian M. Rosenthal c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment