views

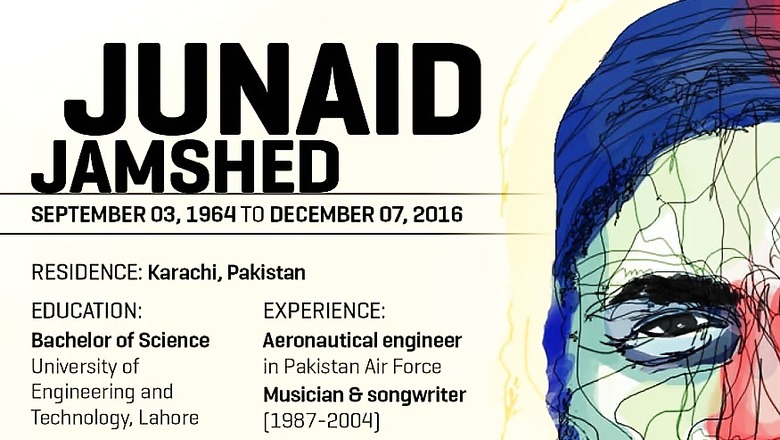

The issue of martyrdom aside, Junaid’s death hits almost everyone experiencing the headiness of youth in Pakistan during the 1980s and early 1990s. Bursting onto the pop/rock stage in the newest way Pakistanis had seen, his band Vital Signs quickly picked up a mass following; hundreds of thousands of culturally starved Pakistanis rising out the 11-year long ashes of Zia-ul-Haq’s martial reign. Before them we had seen Nazia and Zoheb, the Benjamin Sisters, an Alamgir, each of them giving a new voice and personality to pop music but presenting it in the style of national television: young singers, microphone in hand, earnestly singing into the screen as they swayed ever so respectfully from side to side.

The Vital Signs birthed a kind of raw stage energy youth in Pakistan may have seen in more private spaces or on college campuses but they hadn’t had the mainstream authenticity, which included being signed on by labels, being given the royal EMI treatment and getting young-focused brands like Pepsi salivating for their attachment so they too could reach that much coveted youth audience — no small numbers in a small country with over a 100 million people (at the time) most of them young.

The Vital Signs collectively included some of Junaid’s generation’s most impressive musical talents, spawning rival bands and such later successes as Junoon, and eventually with guitarist Rohail Hyatt being the force behind the ultra-successful and much more successful branded content studio under the auspices of Coke.

Travel well my https://t.co/qhI6jUHrZQ in a better world now didn't know I was meeting you for da last time 2 weeks ago... pic.twitter.com/2i91eIQcys — Shoaib Akhtar (@shoaib100mph) December 7, 2016

My heart goes out to the families whose loved ones were lost. May Allah make it easy. Let's say Fatiha for all & sp Junaid Jamshed bhai RIP— Shoaib Malik (@realshoaibmalik) December 7, 2016

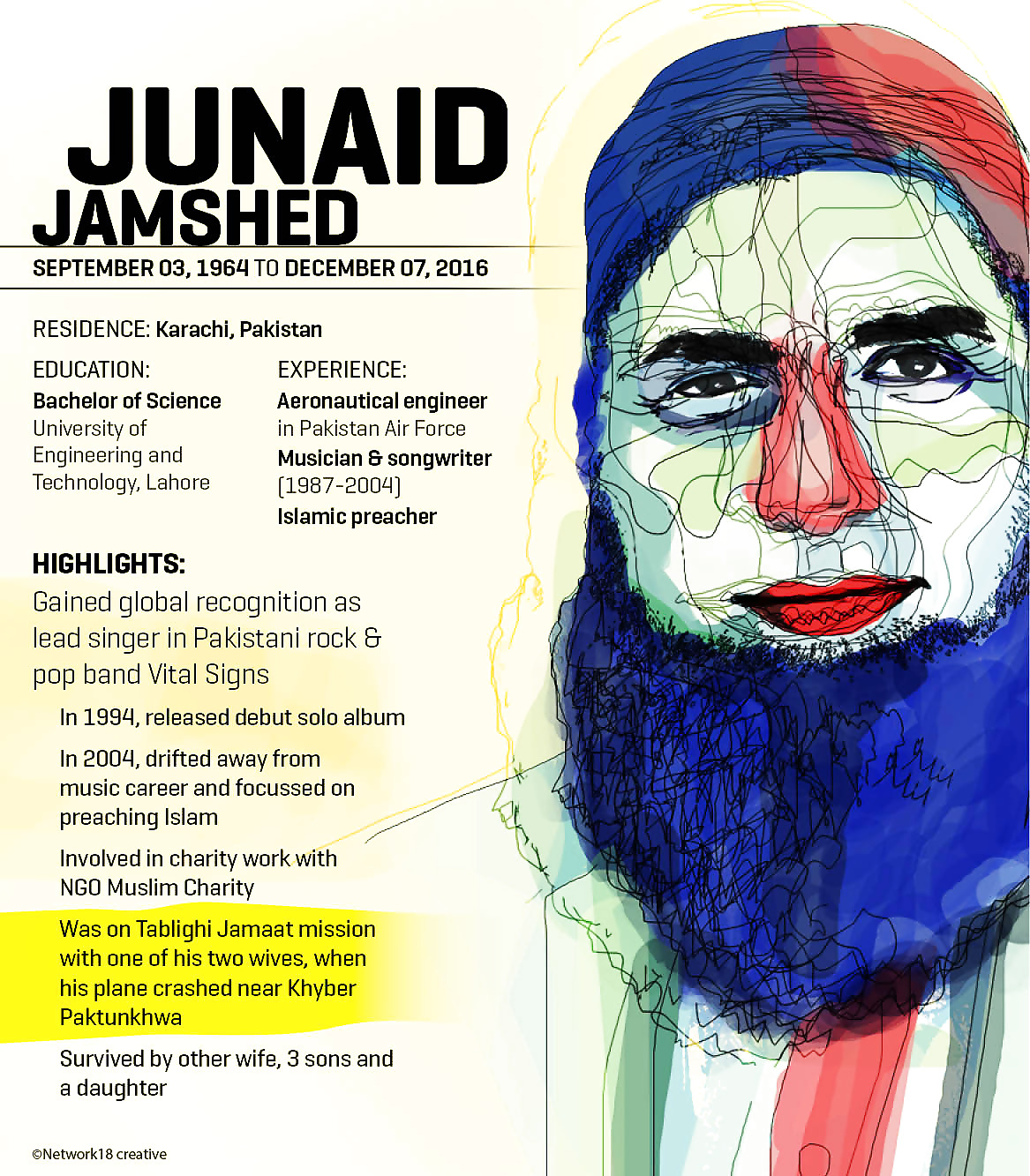

Few people had anything negative to say about Junaid. An overwhelming number of my interviewees — Junaid’s friends and colleagues — had only good things to say about him. He was known to go out of his way for his friends; he had a hard time saying no to people; he tended to overstretch himself. Ultimately when you needed a friend he’d be there. But there was criticism too: one close friend also felt that Junaid had had a choice. The Tableeghi Jamaat had reached out to anyone with popular appeal in an effort to do what missionaries do best: land up in places of conflict and find the right ambassadors to preach their message.

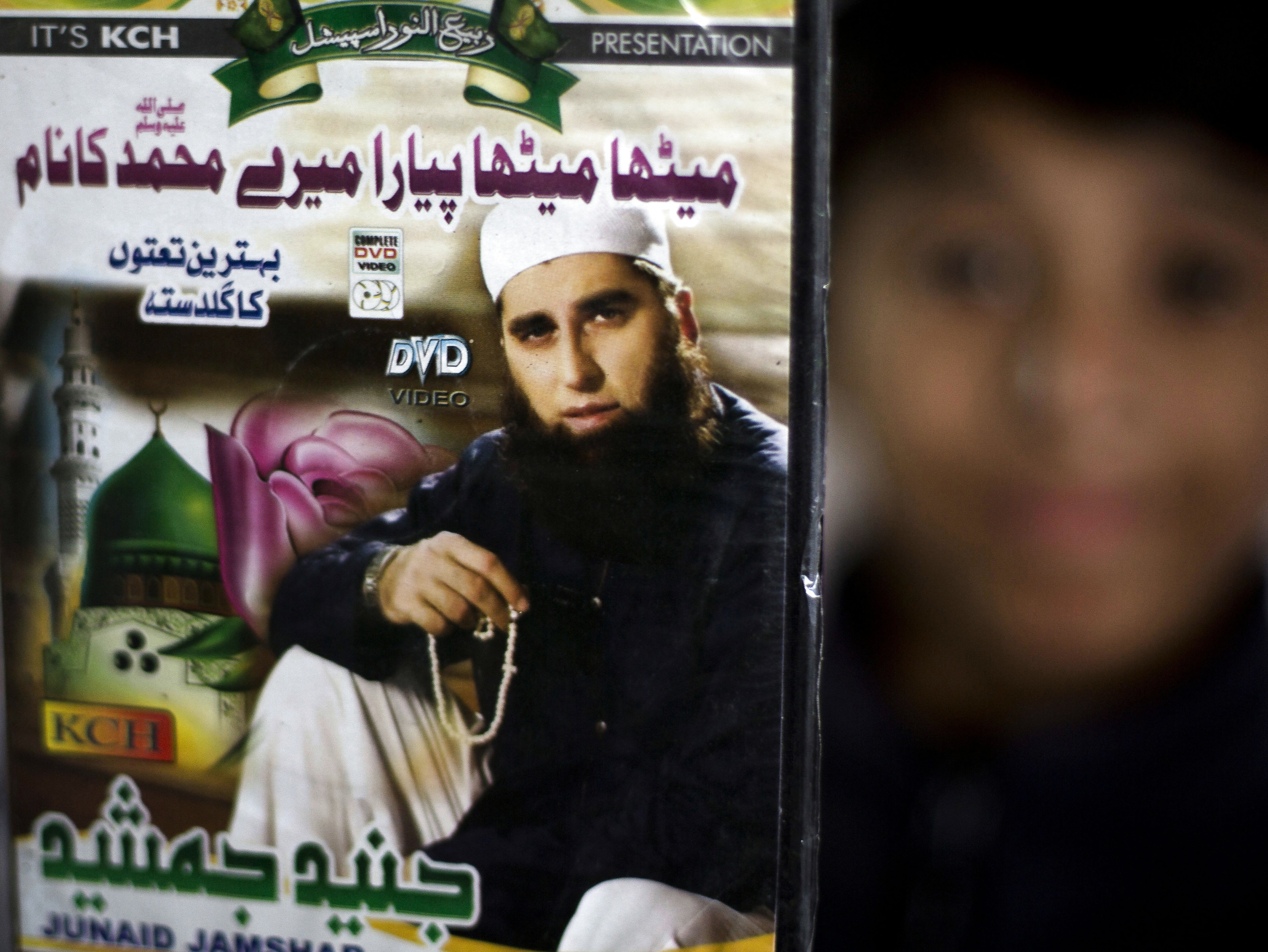

Relatives gather outside the residence of Junaid Jamshed on hearing the news of the plane crash, in Karachi, Pakistan on December 7, 2016. (REUTERS)

In a society like Pakistan struggling with the issue of fundamental identity: how to deal with the conflict of being modern while following what some said the scriptures said you should do. A cynical view of the Junaid story was this: with sales falling with every new album release after he went solo, he needed new direction, a new way to stand out and be loved by Pakistan’s adoring public.

Junaid chose the Tableeghi Jamaat but I don’t think he quite knew what that choice meant. He made public choices that demonstrated his confusion. He shaved his beard. He grew his beard. He shaved his beard. He grew his beard. He condemned singing but he loved to sing (with and without instruments).

Heaven on Earth Chitral.With my friends in the Path of Allah . Snowpacked Tirchmir right behind us pic.twitter.com/ZajcWEKlrG — Junaid Jamshed (@JunaidJamshedPK) December 4, 2016

Junaid's last tweet on December 4.

Certainly the conflict in him was apparent to me through my reporting. The critic who had expressed reservations about the reasons for Junaid’s choice sometimes made sense to me. For instance, when following him on the set of the Ramzaan-themed jeopardy-style contest, Alif Laam Meem, he introduced me to the producers backstage as his biographer. We were both in the room and he knew fully well that I was not his biographer but in that moment he had felt the need to say that.

He had also asked me to come to his house at the crack of dawn, close to 6 am presumably to demonstrate his morning religiosity. When I showed up at the appointed hour, I not only woke up his chowkidar, I also roused a very darkened house. My early morning mission had awakened me to the challenge he had set himself up against.

I kept in touch with Junaid after the piece was published. Some of Junaid’s friends felt that I had been too critical of him but Junaid himself didn’t seem to care, his reaction to that story strengthening the thesis about his need to be in the public arena.

In 2014 a blasphemy case was filed against Junaid for some remarks he had allegedly made against one of the Prophet’s wives. Under serious pressure Junaid quickly apologized via a video statement, offering his ignorance as an excuse. I asked him how things were. “Topsy Turvi,” he wrote. I suggested his combination of dangerous toys, friends, religious ideology and bigoted partners was a mixture likely to produce “topsy turvy.” “Absolutely,” he wrote back, “What our society is made up of.”

“Confused people, including yourself?” I countered.

“I am not confused,” he wrote. “I am misunderstood.”

(Sonya Fatah is a writer and documentary filmmaker from Karachi based in Toronto. The views expressed by the author are personal.)

Comments

0 comment