views

Looking for Symptoms of Kidney Failure

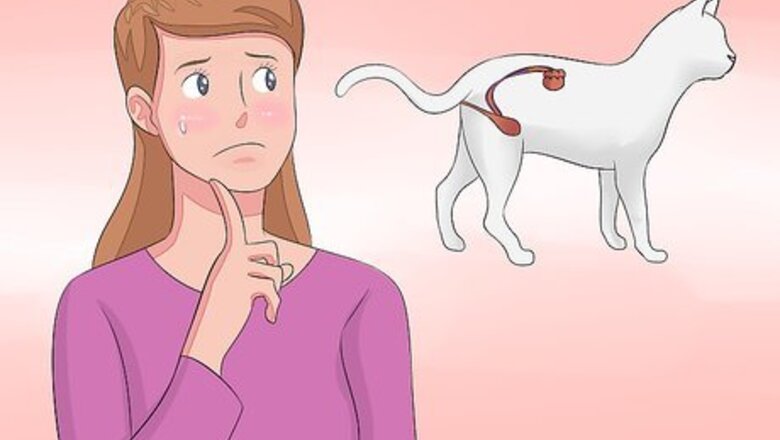

Understand the difficulties surrounding early detection. The kidneys have a huge reserve capacity and it isn't until at least 75% of total kidney function is lost that the cat shows clinical signs of a problem. Thus, by the time a diagnosis can be reached, the cat is coping on a maximum of 25% of the renal capacity when healthy. (This sounds alarming, but remember when people donate a kidney, they automatically lose 50% of their renal capacity and yet do not become ill). Unfortunately, as total kidney function declines, the nephrons (the individual filtration units contained in the kidneys) which are still working are asked to work harder and so their demise is hastened. It is therefore important to identify renal disease in the cat are early as possible because early treatment extends the life of the remaining nephrons. However, early detection is problematic because blood screening is relatively insensitive up to the point where 75% damage has occurred. Many vet clinics offer routine yearly, or six-monthly screening programs for senior (over the age of 7 years) cats. Many cats’ kidneys can compensate even if as many as 90% of the nephrons in their kidneys are destroyed. This will delay a diagnosis if the owner is not looking for signs of kidney failure or it may seem like the symptoms are just a part of the cat getting older.

Watch your cat carefully for symptoms. Kidney failure is usually accompanied by a range of symptoms. The symptoms occur as the body adapts in order to minimize the effects of kidney disease. As an owner you may notice little changes in your cat early on, such as the need to fill the water bowl more often, or empty the litter tray more regularly. These are signs that the cat is drinking more, a sign which should never be ignored. However, many of the signs associated with renal disease overlap with other conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, liver disease, pancreatitis, or infections. This means that a definitive diagnosis cannot be made on symptoms alone, but they are a strong hint that further steps need to be taken to get to the bottom of the problem.

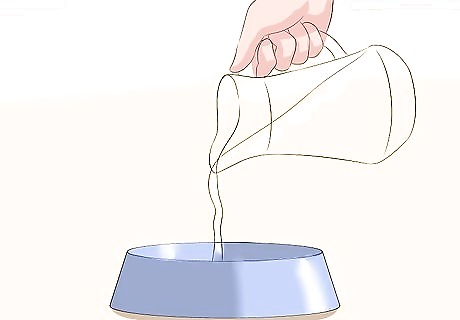

Look for signs of increased thirst. You may notice if your cat develops unusual habits such as drinking from the toilet or if the water bowl constantly needs topping up. Increased thirst happens as a result of the kidney losing its ability to recycle water from the bloodstream. The body loses water through the urine, which is more dilute, and so this water needs to be replaced, causing increased thirst in the cat. Some cat parents report "phantom drinking" — this is when the cat is thirsty but can't reach their water bowl or fountain (often due to joint pain or lethargy), so they remain close to it and lap at the air instead of the water. If you notice a cat staring at their water bowl, especially if their tongue is out, try to move the water source up to their mouth so they can drink.

Take note of whether the cat is urinating more often. Because the cat is drinking more and is not able to concentrate their urine as well, the volume of urine produced is larger. This means the bladder fills more often and the cat needs to urinate more often to stay comfortable.

Cardinal signs are needing to clean the litter tray more often, or a break down in house training habits, such as urinating outside of the litterbox.

Watch the cat for signs of dehydration. Even though the cat drinks more, there is often an imbalance between water loss and water taken in, which results in the gradual development of dehydration. Veterinarians assess this during a physical examination by looking at how quickly the scruff springs back to its normal position. To do this, gently grasp a piece of scruff over the shoulder blades, between the finger and thumb of one hand. Lift the scruff 3–4 inches (7.6–10.2 cm) away from the backbone and release it. In a well-hydrated animal, the scruff springs straight back into the normal position. In a dehydrated animal, the skin loses elasticity which means it returns slowly to the resting position. If the skin takes over a second to slip back down, then the cat is probably dehydrated.

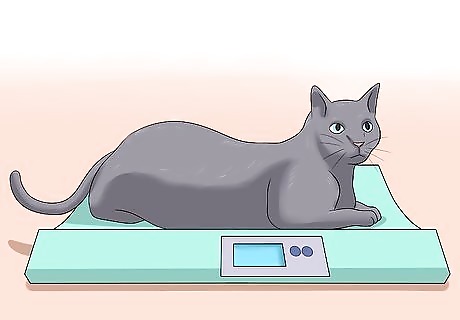

Identify any weight loss. As part of the kidneys' impaired ability to filter, large molecules such as protein tend to leak through the kidneys and be lost in the urine. Protein loss represents an important waste of calories. Another reason for weight loss is that the buildup of natural toxins often makes the cat feel nauseous, which reduces their appetite. A cat that is usually overweight will suddenly become lighter, or a normal weight cat will lose muscle mass. The fat pad between the cat’s legs will also become saggy as it loses the fat deposits.

Sniff your cat's breath. Cats get bad breath for many reasons, including rotten teeth, gum infections, diabetes mellitus, diet, and kidney failure. In kidney disease, it is the toxins that cause the bad breath and this is described as having a typical ammonia-like smell. This smell is not always easy to detect and some people's noses seem better tuned to pick up ammonia smells than others.

Check for oral ulcers. The same toxins that cause bad breath also damage tissues and cause ulceration in the mouth and stomach lining. Of these, you can see the ulcers in the mouth. They tend to form along the margins of the tongue, or where the teeth meet the gum, and they may cause the cat to drool. Again, ulcers do form for other reasons such as viral infections or if the cat has licked a caustic substance, but it remains a sign that needs to be taken note of.

Identify any muscle wastage. Ultimately, when protein loss exceeds intake from the diet, the cat's muscle starts to break up to provide them with the necessary protein requirements. Cats with kidney failure are typically thin, with dull coats and wasted muscles.

Watch for vomiting and a poor appetite. Gastric ulcers caused by a buildup of toxins make the cat nauseous. This results in vomiting and a reluctance to eat.

Checking the Cat's Physical Condition

Feel the cat's kidney size. Scar tissue causes the kidneys to shrink and failing kidneys typically feel smaller than usual. Especially in thin cats, the kidneys are easy to feel in their location sitting beneath the lumbar vertebra (lower back). Gauging their relative size is a subjective measurement and a skill that veterinarians acquire over the years. Don't try to feel your cat's kidneys at home. A normal kidney is usually equivalent in length to that of three lumbar vertebrae, and shrunken kidneys measure less than two lumbar vertebrae in length.

Look for kidney symmetry and shape. Scar tissue forms fairly uniformly throughout the kidney and so the surface of the kidney feels smooth and both feel equally shrunken. However, cancerous kidneys often feel knobbly with a rough, bumpy surface. The latter is an important indication for kidney biopsy because some renal cancers are amenable to chemotherapy, whereas old-age kidney deterioration is not.

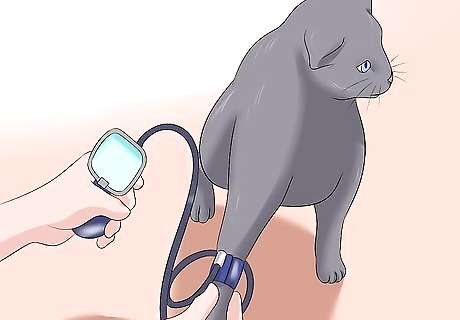

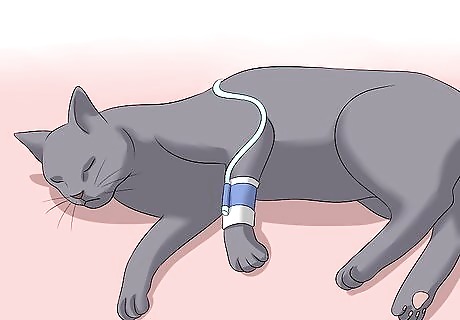

Measure the cat's blood pressure. The kidney breaks down several hormones that control blood pressure. When the kidney is not working properly the levels of these hormones rise which creates an increased risk of high blood pressure o hypertension. On physical examination the veterinarian may see telltale signs of hemorrhage on the retina, or even spot detached retinas, which are a common consequence of hypertension. Once again, high pressure is not diagnostic of kidney failure, but a strong clue that needs to be followed up on. The blood pressure cuff used to measure your cat’s blood pressure is similar to the one used to measure human blood pressure. 120/80 is considered a normal blood pressure for your cat.

Getting the Cat Tested

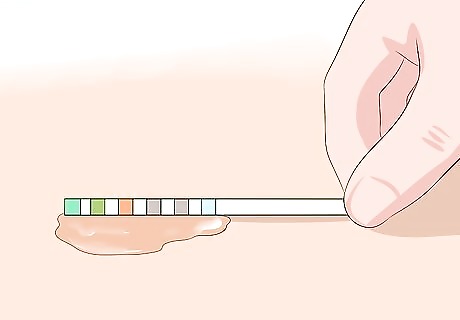

Do a dipstick urine analysis. Urine analysis is an extremely valuable tool for assessing renal health, especially in the early stages of kidney disease. A simple dipstick test can quickly rule out conditions which cause increased thirst such as diabetes, if no glucose is present. A dipstick test also gives a rough indication of the protein content of the urine. A high protein level can result from a urine infection (in which case blood is commonly present in the urine) or kidney disease. If blood is present the clinician will suggest either treating preemptively with antibiotics or sending the urine for culture. Only once the blood has cleared can a decision be reached that the protein is because of leakage from the kidney. Your cat’s veterinarian may also want to perform an Early Renal Damage (ERD) test, which checks your cat’s urine for the presence of microalbuminuria.

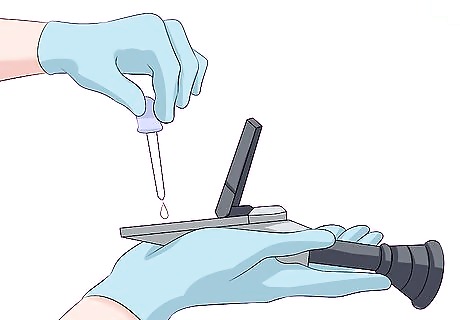

Try a specific gravity urine test. Specific gravity is a measure of how dilute or how concentrated the urine is. Cats are very efficient at concentrating their urine, in order to preserve water. Specific gravity is measured relative to water (which is SG 1.000). A healthy urine SG is between 1.035 – 1.060. Urine below SG 1.035 is considered abnormally dilute. Urine SG below 1.025 is significantly dilute. Dilute urine should contain very little protein, thus a result of a low SG and high protein level is an indicator that the kidneys are not concentrating urine and are leaking protein. This is an important pointer towards kidney disease, which can be detected before changes are evident in the blood test.

Test the urine protein creatinine ratio (UPC). This test measures the ratio of protein in urine to another naturally occurring metabolite called creatinine. The normal value in the cat is below 0.4. Ratios above 1.0 indicate significant protein loss which needs investigating.

Take a sample of the cat's blood for blood testing. Blood tests play an important role in identifying cats that have lost over 75% of their functional kidney capacity. Most useful for diagnosing kidney failure are three indicators: blood urea, creatinine, and phosphate levels. Blood Urea: Normal blood urea levels in the cat are less than 32mg/ml and levels above 35mg/ml are considered to be high. Whilst raised urea in the blood is an indicator of kidney failure, it can be high for other reasons. Therefore raised urea levels alone are not sufficient to diagnose renal failure. Blood Creatinine: The normal level in cats is below 130 umol/l. Any reading above 130 umol/l is likely to indicate renal disease. Creatinine is a waste product of protein breakdown and is only excreted by the kidneys. Phosphate levels: The kidney finds it difficult to excrete phosphate and when kidney function fails the levels of phosphate in the bloodstream rise. Normal levels are below 2.6mmol/l. Unfortunately, high blood phosphate levels cause further kidney damage and so a vicious circle of poor kidney function leading to phosphate retention, which then causes further damage.

Do a test to distinguish between kidney disease and dehydration. High levels of urea, creatinine, and phosphate is a strong indication of kidney disease. However, raised results do not necessarily tell the clinician whether the problem lies within the kidney (i.e. true kidney failure) or if the kidney is under strain because of another condition such as dehydration. To investigate whether the problem is pre-renal (caused by dehydration) or renal, the clinician often suggests rehydrating the cat by putting her on an intravenous drip for 2-3 days, and then repeating the blood tests at the end of this time. If in the fully rehydrated cat the results are now normal, this indicates the kidney is probably functioning normally but was under severe stress. If however the results remain raised in the hydrated cat, kidney failure is likely.

Perform a kidney biopsy only if renal cancer is suspected. Kidney biopsy plays a limited role in the diagnosis of kidney failure. The main indication for kidney biopsy is when renal cancer is suspected, in which case a definitive diagnosis as to the type of cancer can indicate whether chemotherapy would be beneficial or not. The majority of renal cancers present with either large kidneys, or kidneys with knobbly surfaces – which contrasts sharply with the small, smooth feel of kidneys with renal failure. With the exception of kidney cancer, most causes of renal failure are treated in the same way. Putting the cat through the extra stress of an anesthetic and a surgical procedure in order to reach a precise diagnosis which is largely of academic interest is therefore not warranted.

Comments

0 comment