views

- Keep your sentences and descriptions brief throughout the scene to make the fight feel fast-paced and exciting.

- Include vivid, expressive words that activate the reader's sense of smell, taste, touch, hearing, and sight.

- Develop your character's personality by writing about their fighting style, their reactions to the villain, and the decisions they make during the fight.

- Clarify the stakes of the fight before it begins and during the action. When the fight is over, include a resolution for each of the characters involved.

Planning the Fight Scene

Determine how the fight scene fits into your story. Before you start writing, consider the purpose of the fight and how it’ll serve your story. Is it a showdown between your protagonist and antagonist after a long game of cat and mouse? Is your protagonist trying to save a key character? The bottom line of each fight scene you write is that it should have a clear objective and advance the plot somehow. Several different characters might be in the fight, not just two. Note how many characters will be present and what “side” each character is on. Consider the time of day and the mindsets of the characters involved in the fight. Will it be a fight to the death or a fight with minor injuries? For every fight scene you write, try a simple test. Ask yourself, “If I took this scene out of the story, would the story fall apart?” If the answer is “yes,” then your fight scene definitely has a purpose and is worth keeping in the story.

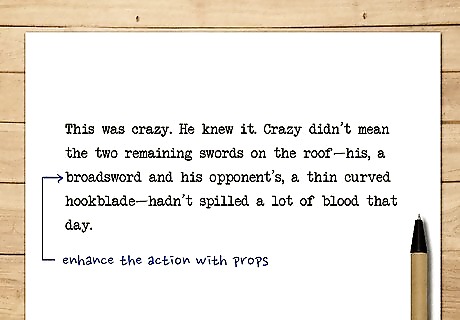

Set the fight in a dynamic place and enhance the action with props. Figure out where you want your fight to take place. It’s important for your locale to fit the time period and setting of your story—but it’s equally important to choose a place that lends itself to an exciting, dramatic fight. Choose a location with interesting topography or one that would have objects your characters could use in the fight. Placing your fight scene at the edge of a deep ravine or on a boat adrift in stormy waters creates immediate tension—your characters could be in grave peril with one wrong move! Setting your fight in a garage full of tools or an antique store creates many opportunities for the characters to grab various objects, crash into them, or use them as improvised weapons.

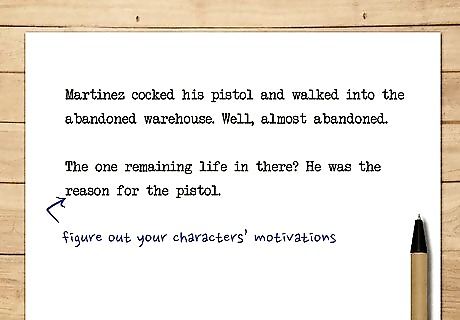

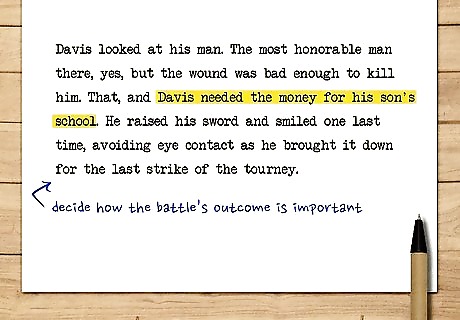

Figure out your characters’ motivations to fight. To build drama—and get readers to care about the characters and the outcome of the fight—it’s important to consider why the character is involved with this fight. Ask yourself a few key questions to nail down each character’s motivations and characterize them accurately throughout the fight. What does this character hope to gain? What does the character stand to lose? What sort of ability does he or she have? What type of training does he or she have? Does this character have cultural beliefs about fighting? Why does the reader care about the character? How can he or she likely relate to the character?

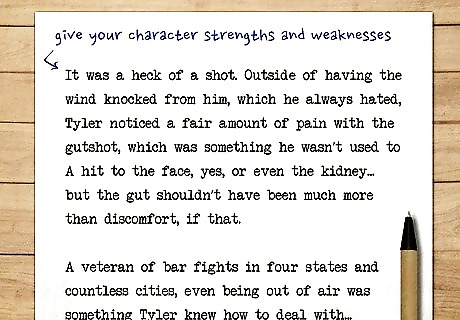

Give each combatant strengths and weaknesses. Before writing your scene, figure out how well-matched each fighter is. What are they best at? What are their weaknesses? Are there any imbalances between them that you can exploit? Each fighter should have some advantages over the other in combat—plus, when you have imbalances, it’s even more satisfying when the underdog wins. For example, you might have one character be so exceptionally strong that they seem to be winning, until your underdog uses their smarts to trick (and defeat) the stronger character. You could also have one character be a very inexperienced fighter matched up against a master fighter, and their surprise win is also how their special abilities manifest, setting up the rest of your story.

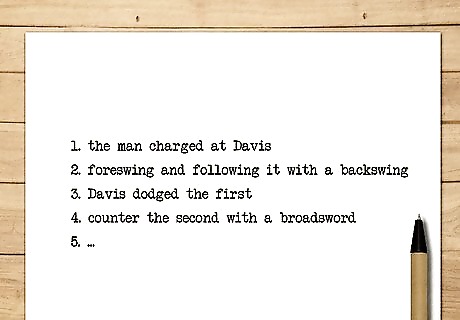

Make an outline describing each action characters will take in the fight. Consider how you want to position characters in the scene and how you'll describe their actions and movements as they fight. Is there a lot of description of each punch and kick? Do you have a clear sense of the movements of each character in the scene? Write up a brief description of each action that's precise and easy to understand.

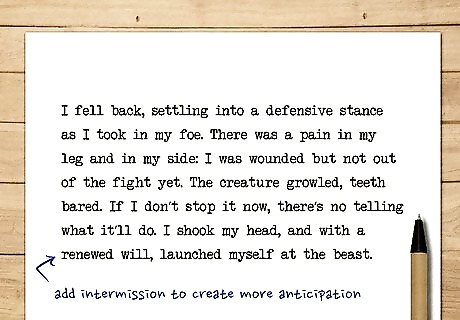

Add an intermission to break up the action and create more anticipation. Nonstop action in a fight scene can make the reader feel fatigued. Instead, break up the action with an intermission mid-fight. Some fight scenes may use dialogue to alter the pace of the scene and keep the reader engaged. Give your characters a chance to breathe, plot their next move, or have a line of dialogue during the intermission. For example: “I fell back, settling into a defensive stance as I took in my foe. There was a pain in my leg and in my side: I was wounded but not out of the fight yet. The creature growled, teeth bared. If I don’t stop it now, there’s no telling what it’ll do. I shook my head, and with a renewed will, launched myself at the beast.”

Decide how the battle’s outcome will change the story. A good fight scene will dramatically shift the stakes of the overall story. Your protagonist may end up wounded, lose a limb that limits their fighting ability, or they may be fatally injured. On the other hand, your antagonist might be defeated in the fight, with your protagonist coming out on top. A fight scene may also create a conflict for your protagonist, as a close ally, friend, or family member may end up being collateral damage in the fight, motivating the protagonist to fight back.

Create stakes for the fight. If you want your readers to care about the outcome of a battle, it needs to have stakes. What does your protagonist stand to lose if they’re defeated? What happens if they lose—or, alternatively, if the antagonist loses? Death is a pretty common stake, so try to think of more than just one! Make it clear to the reader what is at stake so they pay careful attention to the battle. For example, if your protagonist loses their fight, they might fail to stop their enemy from doing something horrible, like annihilating an entire town or killing their best friend. In fights that aren’t as climactic, there can still be stakes. For example, your protagonist might put their honor or skills to the test, and if they lose, they’ll be humiliated or demoted.

Treat each fight as a mini-story. If you aren’t already, familiarize yourself with the concept of Freytag’s Pyramid. According to this concept, many stories follow a similar progression: an inciting incident, rising action, the climax, falling action, and finally, a resolution. It might also help to use Freytag’s Pyramid for your fight scene, and plan the fight like a small story. For example, try to begin your fight scene with an inciting indecent, followed by rising action, where your characters are fighting each other. As your characters fight, create twists and surprises in the narrative. Allow one fighter to start gaining the upper hand. Then, create a climax for your fight. This could be a particularly powerful move or decision that ultimately decides the outcome of the fight. Finally, wind down the battle and offer a resolution—whether your protagonist is left licking their wounds and vows to beat their enemy next time, or they vanquish their foe and win the day.

Drafting the Fight Scene

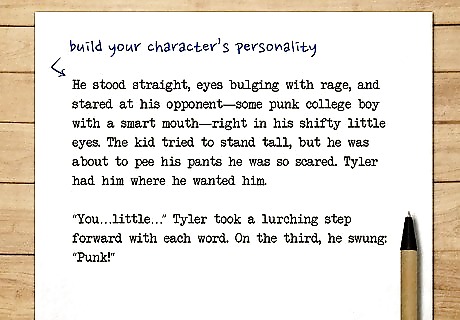

Build your character’s personality through the way they think and fight. Your protagonist’s fighting style should give readers a sense of their character—whether they’re an amateur with street smarts or a more seasoned fighter with great technical skill. Are they honorable? Cutthroat? Do they show mercy or win by any means necessary? Developing a character through a fight scene is smart writing. You can also use fight scenes to trigger changes in your character’s personality as they respond to the escalating conflict. For example, maybe your character normally plays by the rules, but after their friend gets hurt, they let loose and fight in a reckless, uncontrollable manner. On the other hand, maybe your character has spent the better part of your story carving a bloody path to vengeance, and this is the fight scene where they finally learn that it takes even more strength to show an enemy mercy.

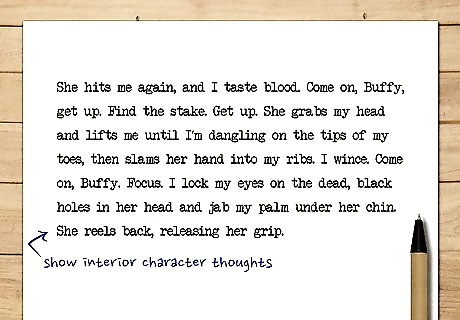

Include interior character thoughts. A real-life fight involves very little spoken dialogue between the fighters; people respond to each other through action rather than speech. However, you can show interior character thoughts to give your reader context for the fight and to show the character’s mindset during the fight. This will give the fight a clear perspective and make it easier for the reader to follow the action. For example, your hero may be facing a challenging adversary and start to feel she is losing the fight. She may have interior character thoughts as she struggles to gain the upper hand. “She hits me again, and I taste blood. Come on, Buffy, get up. Find the stake. Get up. She grabs my head and lifts me until I’m dangling on the tips of my toes, then slams her hand into my ribs. I wince. Come on, Buffy. Focus. I lock my eyes on the dead, black holes in her head and jab my palm under her chin. She reels back, releasing her grip.”

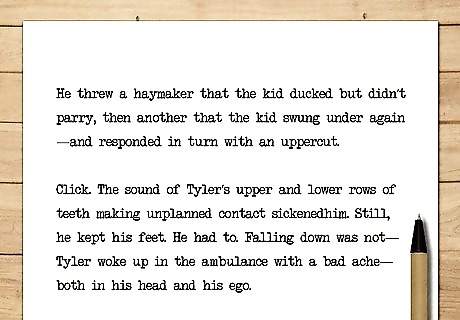

Use descriptive words that activate the reader’s senses. Make a good fight scene into a great one by giving readers visceral descriptions that make them feel like they’re witnessing the fight firsthand. What do the characters see and hear? What does the fight smell or taste like? Include words with strong imagery that can activate all 5 senses: sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch. When using touch, describe how your characters physically interact with each other and any weapons or objects around them. Use sight to show readers what they should be paying attention to most in the scene, whether it’s a character, an object that character is trying to obtain, and so on. Use onomatopoeia (a word based on a particular sound) for hearing. For example, if there’s an explosion, you could write, “BOOM! A clap like thunder filled the area.” Think about what your character might taste. For example, they could describe the taste of the sweat on their lip or the acrid taste of smoke in the air. Can your character smell the ocean air? Gasoline and motor oil? Cooked food? Consider what smells might be present at the location of the fight.

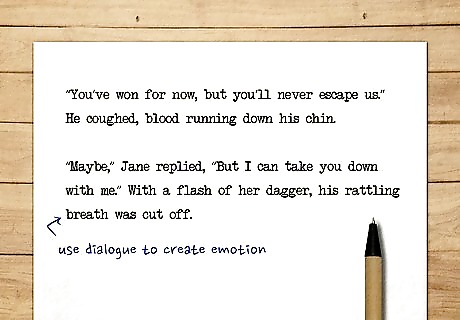

Add character dialogue to create emotion in the fight. Give the fight scene a sense of urgency by writing dialogue between characters; this will help move the scene forward. Dialogue can be used to break up the action, highlight your character’s motivations, and allow your character to deliver witty one-liners or have the final say at the end of a fight. Use short bursts of dialogue, as long speeches can slow down the action. In The Princess Bride fight scene, Inigo Montoya is given snappy lines of dialogue between each swish of his rapier to vary the pace and demonstrate his character in the scene. For example: “Go now, Buffy! Save the others.” “Are you sure, Giles?” Giles sprayed silver bullets into a wall of vampires. I watched a few slam against the concrete, splattering guts and blood. The rest of the pack moved closer. Giles glanced at me over his shoulder. “Go Buffy, now!” I run. A parting shot at the end of a fight can be satisfying for readers. For example: “You’ve won for now, but you’ll never escape us.” He coughed, blood running down his chin. “Maybe,” Jane replied, “But I can take you down with me.” With a flash of her dagger, his rattling breath was cut off.

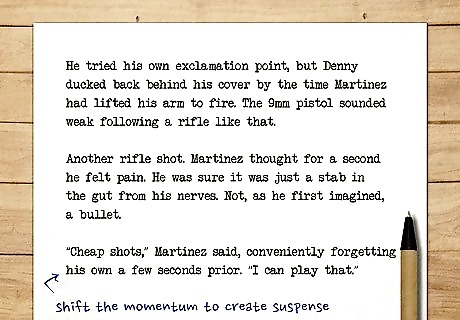

Shift the momentum throughout your fight scene to create suspense. In a good fight scene, readers should understand which character is winning with every action that happens. However, the same character doesn’t have to be winning for the entire fight! Fights are more exciting if the momentum shifts several times, giving your protagonist the upper hand in one second and their enemy the upper hand in the next. There are a couple of ways to shift the momentum. For example, the enemy might parry a strike from your protagonist and then hit them hard, making them lose their balance. You can also shift the momentum using thoughts rather than actions. For example, your protagonist might have a moment of worry or fear that they’re going to lose. Each time the momentum shifts, make it clear which character now has the upper hand. Don’t be afraid to let your character make mistakes as they fight. Actual fights are messy and chaotic, and mistakes are natural. It’ll make your character feel more real and relatable to readers.

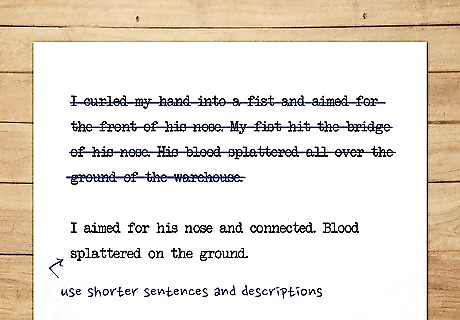

Keep up the pace with shorter sentences and descriptions. Fight scenes can be tricky in written form because you can’t rely on visuals to tell readers what’s happening. It’s easy to get bogged down in details, which slows the pace of the entire fight scene down in turn, and the pacing is important. Keep your sentences short and concise, and don’t let the scene get too long overall. In real life, fights begin and end fairly fast! Avoid a blow-by-blow description of each character's action, as this will feel too technical. The scene should feel chaotic, much like a real fight. Keep all actions simple, clear, and to the point. Steer clear of long sentences and avoid using adverbs or too many adjectives in the scene. This may confuse and distract your readers. Ultimately, the length of a fight scene is up to you, but generally, only a climactic final battle or an epic battle between armies should span many pages or chapters. For example, short sentences like “I aimed for his nose and connected. Blood splattered on the ground,” are more effective than longer sentences such as: “I curled my hand into a fist and aimed for the front of his nose. My fist hit the bridge of his nose. His blood splattered all over the ground of the warehouse.”

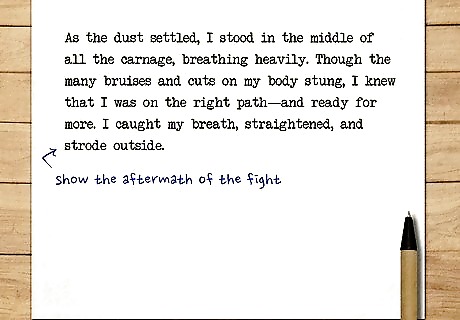

Show the aftermath of the fight. In the aftermath of a real fight, you bruise, you ache, you hurt. Consider how your characters will feel after the fight, especially given whatever the outcome of the battle might be. Give your character a realistic recovery period, and think about how the adrenaline rush of the fight will help them recover or get away from the scene of the fight. If your character suffers a cut or stab wound, for example, you’ll have to show their recovery (or, if you’re jumping ahead in time, their scar from the wound). Bruises and cuts on a character’s face might limit their ability to eat or chew. If a character is in a fight for the first time, they may feel shock and anxiety from the fight—or they may feel hardened and ready for more. For example: “As the dust settled, I stood in the middle of all the carnage, breathing heavily. Though the many bruises and cuts on my body stung, I knew that I was on the right path—and ready for more. I caught my breath, straightened, and strode outside.”

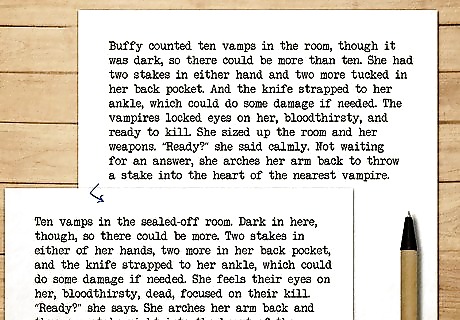

Overwrite, and then edit down the scene to cut unnecessary detail. You may end up including more detail than necessary in your first draft of the scene. It’s tough to plot out a fight scene’s action without overwriting it, and that’s okay! Focus on capturing each character’s movements, actions, and reactions in the scene. Then, proofread your first draft and pare down the language, so it’s concise and to the point. First draft: “Buffy counted ten vamps in the room, though it was dark, so there could be more than ten. She had two stakes in either hand and two more tucked in her back pocket. And the knife strapped to her ankle, which could do some damage if needed. The vampires locked eyes on her, bloodthirsty, and ready to kill. She sized up the room and her weapons. “Ready?” she said calmly. Not waiting for an answer, she arches her arm back to throw a stake into the heart of the nearest vampire.” Second draft: “Ten vamps in the sealed-off room. Dark in here, though, so there could be more. Two stakes in either of her hands, two more in her back pocket, and the knife strapped to her ankle, which could do some damage if needed. She feels their eyes on her, bloodthirsty, dead, focused on their kill. “Ready?” she says. She arches her arm back and throws a stake right into the heart of the nearest vampire.”

Research & Writing Tips

Focus on writing in your own unique style. Ultimately, your writing style (like everyone’s) reflects a combination of the books you’ve read over the years and the different things your language and writing teachers have taught you. Still, the product of all those influences is a voice that is unique to you! Rather than trying to capture another author’s voice, find your own voice and how you like to write best. The best way to find your unique voice is simply through regular practice. Make time to write as consistently as you can, and your writing style will naturally emerge. Read more books, as well. The more you read, the more you'll develop your own voice and gain inspiration.

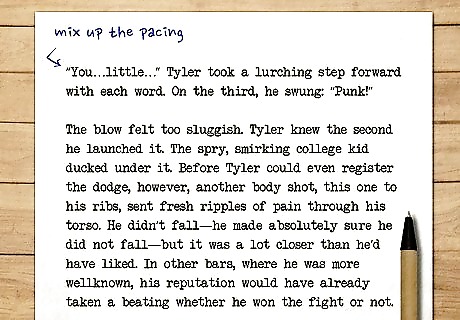

Mix up the pacing of different fight scenes, so each one feels different. Are there multiple fight scenes in your story? Odds are, if your character needs to fight, they probably have at least a couple of altercations throughout the book. To keep your fight scenes dynamic and entertaining, try to switch up the pace. A more epic fight might take up an entire chapter, while a low-stakes fight might only need a single sentence. Remember, it’s okay to experiment and see what pacing and length work best for the particular fight scene you’re working on. That’s what drafting (and editing) is for!

Read examples of fight scenes for inspiration. Think about a fight scene in a novel or short story that you found effective and full of action, and identify the parts of that scene you liked best. Are there any aspects of that scene that could help you set up your own fight scene? It’s important to write in your own voice, but you can still take inspiration from other writers. You could check out examples such as: The fight between Hector and Achilles in Homer’s The Iliad. The fight between Hector and Achilles has become a classic model for fight scenes in literature. The fight between The Man in Black and Inigo Montoya in William Goldman’s The Princess Bride. This is a great example of a sword fight, full of action and dialogue packed with wit and humor. The duel between Macbeth and Macduff in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. This pivotal scene is the play’s final showdown; though it’s originally a sword fight, it’s been reinterpreted as a fistfight and a gunfight in modern productions. The battle between Percy Jackson and Kronos in Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Last Olympian. This is another great sword fight; the battle lasts for at least 10 chapters, with lots of detailed action.

Take a fight class to understand better what real fights are like. If you’ve never been in a fight, do some hands-on research and try a basic martial arts or contact fighting class. This can give you a better sense of what a fight might feel like and the true impact of a blow to the body. If you need to write a story scene with an inexperienced fighter, fight classes can also help you understand their perspective. Ask your instructor about common responses between fighters during physical encounters. If you have no experience being in a fight, you’ll react differently than a seasoned fighter. Consider how a professional fighter might approach a fight; they’ll likely be relaxed and focused. Good fighters can see a punch or kick coming, have constant training, and can focus on how the body moves in a fight.

Learn about various weapons so you can describe them accurately. If your fight scene involves the use of weapons, do some research on each weapon you plan on writing about before you finalize your scene. Look up how the weapon is meant to be wielded, what fighting styles are associated with it, what kind of damage it does, and even what kind of mistakes someone could make while using it. For example, a swordfight would likely look very different from hand-to-hand combat in terms of the moves your characters would use and the damage they’d inflict on one another. In a historical fiction novel, your characters’ weapons and fighting style should match the setting. A samurai in feudal Japan would be taught from an early age to use multiple weapons. A fight scene in a fantasy book may be filled with fantastical weapons or fighting abilities. For example, the world of "Harry Potter" includes spells and magical objects. Consider how the weapons and fighting styles of the characters match the tone and setting of the rest of the book.

Comments

0 comment