views

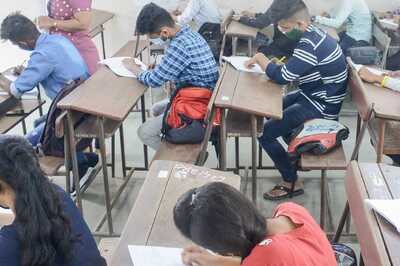

KOCHI: The recent news about an Irinjalakuda-based CBSE school fining students who used Malayalam in their conversation on the campus instead of in the school’s official language English is disturbing. No less disturbing is the wording used by some intellectuals in condemning the action of the school authorities. It is well recognised that Kerala’s egalitarian society is high and wide on literacy but not so high on higher education. Literacy may not be so widely distributed elsewhere in the country but there are pockets of excellence there that cover up their uneven spread in literacy. Underpinning such excellence is their proficiency in English language. Of course, English is being taught compulsorily in Kerala’s schools and colleges. But, do we provide the students with the ambience required for grasping and mastering the English idiom, its ways of thinking, speaking and writing? It cannot be disputed that unless you can think in the language you are supposed to master, you can’t get a grip on that language. Language learning starts with listening, thinking and speaking in that language. That is why babes learn their mother tongue quick and fast. They don’t begin with alphabets and grammar and sentence structuring. Start first with listening, thinking and speaking, followed by the rules of the language. That is the natural order. In this context, I remember my first encounter with economics as a general knowledge subject in the B Sc syllabus in late 1950’s. I found this subject greatly more language-intensive than most other branches of humanities. In the beginning, my problem with economics was not exactly with its theory but with its English and my limited vocabulary. When the vocabulary problem was overcome with constant use of dictionary, individual sentences and their nuances eluded me. With repeated reading this problem too was overcome. Then I noticed I could not cogently grasp the continuous thoughts expressed in paragraphs. This too could be surmounted with application and industry. The next problem was with individual chapters. It was difficult to grasp their overall sense and essence. When that was solved to a reasonable extent, the next issue was with the textbook as a whole, that is, to understand its theme on a larger canvass in a holistic manner.It took an agonizingly long period of repeated efforts for me to get to it. When I had become confident about the subject and its ramifications, the next issue staring at me was how to formulate and communicably verbalize my thoughts in my own way while answering possible questions arising from the subject. Then it became a question of time management. Was it justifiable for me to devote such a disproportionately long time on the GK subject at the expense of my main subjects Mathematics and Physics? After all it was sufficient to get pass marks in the GK subject; the marks scored in the GK subject wouldn’t be counted in the grading and ranking in the final exam.My similarly handicapped classmates from Malayalam medium schools took a practical view. Don’t worry over the GK textbook. Keep it permanently closed; instead, “by-heart” the notes dictated by the teacher. A practical view of course that would incidentally beat the very purpose of introducing this subject as part of the curriculum.I have often wondered in my later years: Couldn’t an average student with a good grounding in English in his school days have mastered this elementary economics in just a week’s time? And how much we struggle in our career in later life because of our initial handicap in English! And how much time we devote in our productive life in order to get over this handicap!Look at China’s parallel experience. To quote their Prof Lin Lin, “It’s high time we remedied the phenomenon of “deaf English” and “dumb English” (when students can read, but cannot speak English fluently, or understand what people say).” Some Chinese students say that although their vocabulary is good, they cannot express themselves in English. “After ten years’ English learning, they are still ‘deaf and dumb’.” The difference between us and the Chinese is that they readily recognize their handicap, while we do not see ours.The Irinjalakuda school probably wanted to remedy this by questionable means.(The writer is formerExecutive Director, IDBI)

Comments

0 comment