views

New Delhi: It’s around 3 am, and I am riding pillion with Kareem, a meat shop owner in New Delhi. As the wind on an early, humid morning slams against my face, I turn around to see Mehmood and Dilawar, also meat shop owners, following our lead.

After almost an hour’s drive from Nizamuddin Basti, we are in the vicinity of the slaughterhouse in Gazipur. The air stinks with the smell of meat, blood and sweat. “The smell remains, but there’s almost no business now,” Kareem tells me.

I walk in, after getting my IDs checked and the three meat shop owners backing me up saying I was ‘their friend’, into a packed house. This is the bhains mandi (buffalo market), where the animals are first brought in by their owners for sale.

Animals were being pushed outside tens of trucks for the farmers, middlemen and buyers present at the mandi. And there was a discordant cacophony of voices. “Pregnant buffalo for Rs 70,000 and the older one for Rs 25,000,” shouts one man. “Give me the one for dairy, but bring the price to Rs 50,000,” shouts back another.

There is utter chaos, but all eyes and ears are on the cattle up for grabs and their prices. “The mandi houses buffaloes, sheep, goats and other cattle. They are brought in by farmers from Punjab, Haryana and sometimes Gujarat and Chhattisgarh too. Some sold for dairy, and the others, which the doctors deem old, are sold for slaughter,” says Kareem, with a hint of dejection. The business, however, has dwindled off late.

Mohammed Dilawar at work in his buffalo meat shop at Nizamuddin Basti. (Debayan Roy/News18.com)

A couple of weeks ago, the central government rolled out a ban on sale of cattle for the purpose of slaughter at marketplaces. The rule has hit every stakeholder in the meat sector: dairy farmers, meat shop owners and traders.

The fear of being targeted, for one reason or the other, is visible on the face of nearly everyone in the mandi. “Earlier, we had the option to choose a buffalo which was healthy for slaughter. Now, we don’t. The doctors checking the animals are in a rush to wrap things up as fast as possible,” said Mustafa, a meat wholesaler from Kalkaji.

As the business at the mandi was underway, I followed some people who were done with their sale and purchase. They were slowly making their way to the only legal slaughterhouse, catering to farmers in Delhi, Punjab and Haryana.

It’s around 5:30 am, and I see a swarm of people waiting in line to get their animal slaughtered. “The farmers usually arrive around 5-5:30 am, and leave by noon with the meat. The rush was such. But now, with negligible business, the waiting time has reduced drastically,” says a dejected old man in the late sixties.

Delhi’s lone slaughterhouse is doing one-fifth of cattle business than a few weeks ago, with farmers either too scared to bring their buffaloes to the market or moving to trading sheep and goats, which, many think, is now ‘safer’.

“This new rule has made life hell for us. Even when I have to sell my animals for slaughter, I declare that they are for dairy,” Shankar Dhyanchand, a 60-year-old farmer from Sirsa, Haryana, tells me.

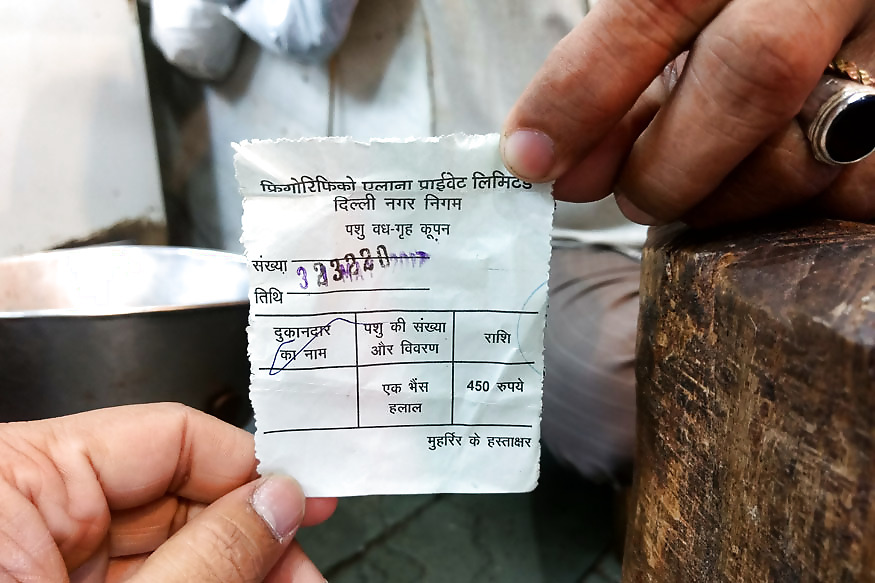

Each meat shop owner pay a tax of Rs 450 to MCD for transporting one buffalo for slaughter. (Debayan Roy/News18.com)

Widespread reports of cow vigilantes resorting to violence and harassment, at times leading to deaths of those at the receiving end, has only added to the fear.

'Save cows if you want, spare the buffalo'

As I stand at the slaughterhouse among farmers waiting for the meat, I am a party to their discussions. One of them is how the government has put the livelihoods of thousands of people at stake.

“Save the cow if you wish, but the buffalo has nothing to do with it… right? Including buffaloes in the ambit of cattle will spell doom for many like me,” Muhammad Qamar, a cattle farmer from Kapurthala, tells me.

The violence associated with cattle slaughter has only cemented farmers’ resolve: stay away from cattle as much as possible. But the resolve has come at a cost. The income many earned from selling buffaloes was not huge, but was better than what they were making from sheep and goats. Farmers’ income has fallen, leading to a trickle-down effect on their daily life.

Farm-to-fork, how?

This is a misplaced notion, I’m told. There is no popular concept of animal farms in India to carry out farm-to-fork policy.

Pramod Kumar, housekeeper at the bhains mandi in Gazipur, says the farm-to-fork principle was “totally impractical” in India.

“There are animals which are brought here for both dairy purposes and slaughter. Even when they are on their way to a legal slaughterhouse, the farmers are scared of being rounded up and the traders are afraid what will happen if they are caught with meat. In such a scenario, how is it possible for anyone to go to a farm? More importantly, where are these farms?” asks Kumar.

My community, a farmer says, does not rear cattle for slaughter. They always do it for dairy purposes. “There are no such farms where farmers are rearing cattle only for slaughter. It’s never existed in India. How can the government expect such farms to crop up just like that,” the farmer says.

Mohammed Abbas, a meat wholesaler at the Gazipur mandi, joins us and calls farm-to-fork principle a mere joke. “It’s not just the farmers who are suffering. We are at the receiving end too. Earlier, around 1000 buffaloes used to be brought in here, now it’s down to just 200. The government, along with the notification, must also tell us where these farms are so that we can survive,” Abbas says.

The Bhais Mandi at Gazipur which used to buzz with animals a month ago now runs empty. (Debayan Roy/News18.com)

'It looks like an agenda'

To start with, many believe that the notification has nothing to do with ‘prevention to animal cruelty’. How can you discriminate against animals when you talk about saving them, rue the farmers and traders.

“It’s a deliberate attempt to make lives of Muslims and Dalits, who are directly involved in buffalo trade, more difficult. We support the ban on cow slaughter, but why buffalo? The government thinks it’s only us who are dependent on buffalo. Buffaloes eat meal worth Rs 500 a day. With the farmers struggling to earn that much for their entire family, how are they expected to take care for buffaloes?” says a meat trader from Nizammudin Basti.

'Buffalo exports have dipped, lives are at stake'

I walked out of the slaughterhouse to get on the phone with Fauzan Alaivi, spokesperson of Meat and Livestock Exports Association.

“There is a lot of demand for buffalo meat, but there’s no supply. It all started with demonetization and then came this notification. Government records show that buffalo meat exports have fallen by 11% from January to June. Markets have become dysfunctional. Most farmers are scared of vigilante groups. This is not Switzerland that farm-to-fork can be implemented with ease,” says Alaivi.

Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) also expressed concern. “We are only a tertiary branch of the government and only execute orders, but I can’t deny that there is fear among farmers,” Dr Prahlad Kumar, additional director at the MCD’s veterinary sciences department says.

India’s slowly becoming a nation of misplaced notions, says Alaivi. “We did a survey after demonetization. Around 95% people who buy buffalo meat, out of the 10,000 we surveyed, are Hindus. So does this notification have religious roots? No. There are meat processing units in only five states. Now, what do the farmers, who stay in interior villages, do with their buffaloes? The government has no response to any of that,” he adds.

Comments

0 comment