views

The journey from Delhi to Nabha in Patiala had many halts, each an attempt to engage with those involved in crop residue burning. However, the farmers were reluctant, either unavailable or unwilling to speak on camera. This silence only deepened the question: why, in 2024, does this stubble burning practice continue despite the imposition of fines and FIRs? Is it the only option or is it the convenient one?

As we approached Nabha, a stroke of serendipity led us to our story. At a level crossing, our driver spotted smoke in the distance – an obvious sign of stubble burning in Punjab these days. Following this, we arrived at a field where our suspicions were confirmed.

Approaching the field, we exercised caution. Our video journalist, Sumit Jaguri, was instructed to seek permission before filming – a precaution that proved fruitful. The farmer not only allowed us to record but also warned us about the health hazards of the smoke. When questioned about the rationale behind burning stubble despite knowing its harmful effects, the farmer responded in Punjabi, “How else will the next crop be sown if we don’t set fire?” This statement summarises the core of the issue – farmers view stubble burning as a quick and easy method to prepare fields for the next crop cycle.

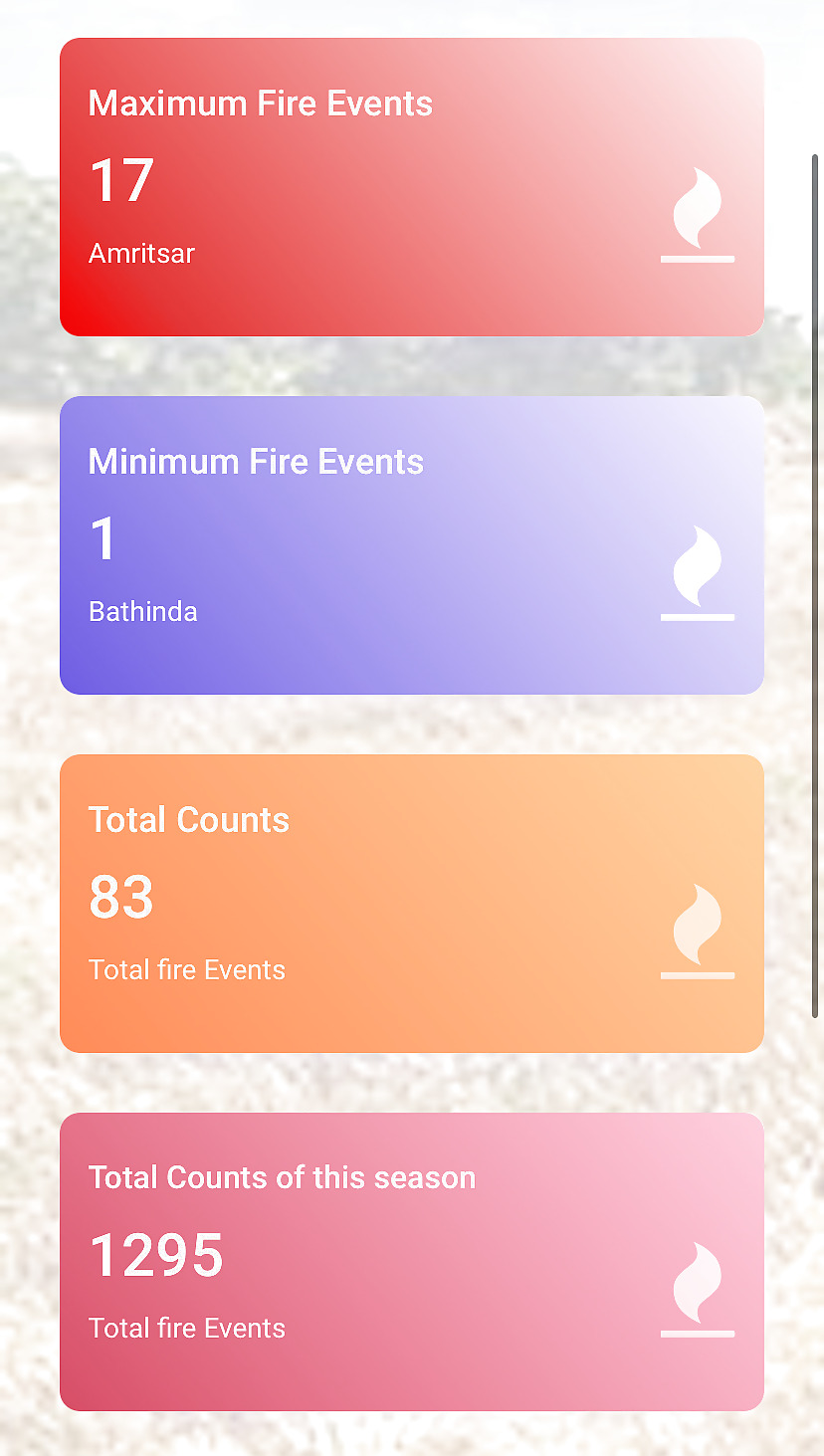

According to the Punjab Remote Sensing Centre in Ludhiana, satellite detection recorded 83 incidents of stubble burning as of October 17. This year, the total number of incidents in Punjab has reached approximately 1,300 cases for the season. Although this number is comparatively low, experts emphasise that the mere count does not determine the impact. The effects depend on various factors such as the area affected, wind direction, and other variables.

Jagdeep Singh, the owner of the field we visited, provided a candid insight into the farmers’ predicament. “Every year it happens, people like you come, record us and go. Nothing happens and nothing can happen,” he said, expressing a deep-seated frustration with the system.

“We cannot go for machines even with the subsidy,” he explained, suggesting that the government’s efforts to promote mechanical alternatives are falling short. “The factories that they said have been set up to take our paddy never come to us or ask for money,” Singh added, pointing to a breakdown in the promised industrial solutions as well.

Perhaps most strikingly, Singh challenged the widely held belief about the smoke’s impact: “This is a matter of 7-8 minutes only. You see yourself. This smoke will vanish here only. They are fooling us all by saying it goes to Delhi and creates pollution.”

Indeed, we witnessed the field transform from golden to blackened earth in mere minutes, with the smoke seemingly dissipating quickly. However, this perception requires scrutiny and underscores the need for better farmer education on the far-reaching effects of stubble burning.

‘You Think It’s As Easy As Govt Claims?’

Near the burning field, we met Harmer Singh, a local farmer leader affiliated with a farm union. In a 40-minute conversation, he painted a comprehensive picture of the challenges farmers face. He also said that farmers are ready to go for options but those options should be feasible enough.

Pointing to a nearby field where potato sowing was underway, Harmer explained the timeline: “He burnt Parali 15 days back and now he is sowing the potato today. Those who are burning today will take next 12-15 days. You think it is as easy as the claims of the government?”

Harmer echoed Jagdeep’s concerns about machinery and subsidies. He proposed an alternative solution: “We had asked them to give us 200/quintal so that we can only accumulate and send it to them, but they think this money will be a big benefit for us.”

Harmer dismissed Pusa Decomposer as a “long rejected solution,” claiming it brings insects to the next crop. “No FIR can stop it because a farmer cannot waste time and crop,” Harmer asserted, highlighting the economic pressures farmers face.

This is not all. Farmers standing along with Harmer said that Pusa-44, the variety that they are asked not to use, is the one buyers look for when purchasing from them. The alternatives suggested have no buyers.

Farmers, indeed, have problems to face, but the fact also remains that burning residue is an easy and viable solution for them. While they want to do away with the practice given that a lot is happening around it, nothing else work for them.

In the meantime, Delhi has started recording AQI in the poor category, prompting the Supreme Court to ask tough questions from states like Haryana and Punjab. The states, like always, will have the alternatives as an answer, and while this may suffice the need for submission, on-ground conditions seem likely to continue to become a major problem this time around too.

Comments

0 comment