views

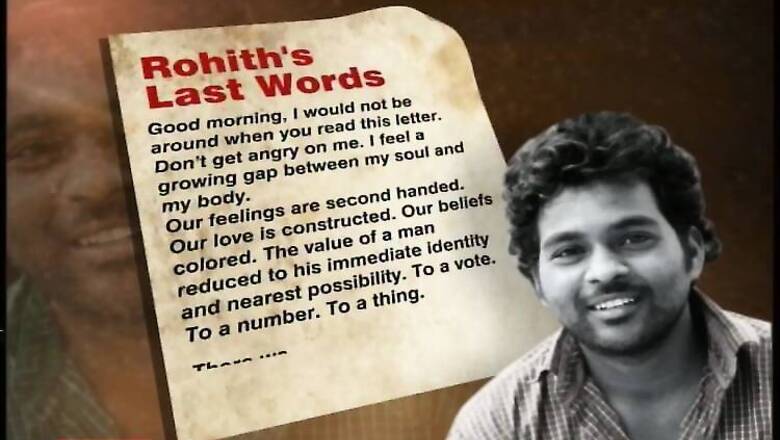

The tragic suicide by Rohith Vemula, a second year PhD student at Hyderabad on January 17, 2016 inside a hostel room came as a rude shock to the collective conscience of the nation. In his suicide note, he shared the dreams he had and how he was leaving this world- disillusioned and heartbroken. He is the latest casualty of the caste system.

However, it will be a vague belief that this is just an incident of hostel eviction, suspension, discontinuation of fellowship on a disciplinary ground to a student in a university. It is the matter of choice for a Dalit student to draw his ideological substance and a moral compass from Ambedkar.

He cannot be persecuted for joining a particular organization and holding a point of view. It is the matter of his right to speak on issues of national importance. He probably spoke against the hanging of a convict and was quickly branded by the local MP as anti-national. He was thrown out of the campus and his fellowship discontinued.

There are hundreds of intellectuals and civil society members who are against death penalty. We are prejudiced and a status conscious society. We do not appreciate a Dalit speak like upper caste Hindu. There are historical fault lines and they run deep.

There was a time in this country in 1920s when only 4 % of upper caste Hindus had the total domination over higher education. Now they are made to rub shoulders with the students coming from lower strata of the society. In 1931 census, Hindus were 68.2 % of the total population. Out of this, 21.1% were from “Exterior Castes” also named as “Depressed Castes”, later called Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The grant of a separate electorate to these castes through Macdonald Award would have reduced the position of Congress to the representatives of only upper caste Hindus. This was the sole reason for Gandhi virtually forcing Ambedkar to Poona Pact (1932) by going on fast unto death. This helped cover up the problem of caste entities and strengthened Congress’ claim to represent all Hindus but allowed the posturing of the upper caste Hindus as ‘donors’.

Prof. Satish Deshpandey in his paper ‘Caste and Castelessness’ (2013) writes:-

“The Poona Pact agreed to significantly increase the guaranteed political representation for the Depressed Classes, but a very heavy price was paid for this ‘concession’, as Ambedkar realised only too clearly…. [T] he grant of reservations reduced the Depressed Classes to the status of supplicants for whom a special concession was being made by the majority that ‘ owned ‘ the nation. This effectively positioned the upper-caste minority (which was in control of the majority) as the de facto owner of the nation, with the power to grant favours to this or that subgroup. It is this mindset that has shaped upper caste common-sense on issues of caste and especially reservations.”

The root cause of the alienation of a Dalit student lies in the above mindset wherein he is reminded that he owes his presence in the campus to the concessions given by the dominant Hindu castes. The political climate of the university campus also does not help. The character of the student movement in the present times has hit a new low in this country. The extreme radicals, right wing jingoists, money and muscle power, all have infiltrated into the campus politics. This, in turn, leads to the instances of intolerance, violence and cast conflicts amongst the students.

The caste based discrimination is not a new phenomenon in this country but the hotbed of such practices was mostly the rural society. Now it has taken universities, offices and even urban surroundings in its fold. After independence, the scenario was expected to change under a liberal Constitutional scheme but that did not happen.

Prof Rajni Kothari in his paper ‘Rise of The Dalits and Renewed Debate of Cast’ (1994) writes:-

“The long-held assumption that as the project of nation- building gets under way and democratic rights are extended to the people, that as the development process also gets under way and more and more people and communities benefits from it all and the sources of poverty, unemployment and human misery are eliminated, and that as the productive forces get unfolded and the dialectic of history gets working, there will be no need for ‘parochial’ structures of caste, community, tribe and various feudal vestiges and that people will enter into new relationships of a more secular and political kind.These assumptions have since been belied.”

One of the reasons for this failure arises from the ugly truth of electoral process in India, which in place of removing the caste with the help of a liberal democratic system, has rather strengthened it.

Prof Andre Beteille in his paper “The Peculiar Tenacity of Caste” (2012), writes:-

“After Independence, the political conflicts among castes became more widespread and more intense. New rivalries and new alliances between castes, sub castes and groups of castes began to arise.”

He further writes:-

“With the adoption of adult franchise, the countryside began to experience the pulls and pressures, and also the thrills of electioneering on an unprecedented scale. Loyalty to caste provided an easy basis for mobilizing electoral support. Where caste consciousness was dying down, it was brought back to life by the massive campaigns that became a part of every election.”

The student politics in the university is generally held to be a nursery for the budding politicians and many in Parliament today have a background of active student politics. This nursery is supposed to inject fresh, youthful and modern ideas into the political discourse of the country. But it is a sad reflection of the student politics in India that the young students are wasting their energy in the age old caste conflicts instead of using the modern education system to eradicate this malaise. As the mainstream parties are leaning towards social engineering (read ‘caste combinations’) for electoral success, their frontal organizations and student’s wing have come to acquire the same perspective.

The menace of caste segregation has managed to travel to the university campuses from the rural hinterlands. So have come the attitudinal conflicts between the caste Hindus and Dalit students. The universities have not been able to support a Dalit student from condescending Hindu upper castes. In fact, the attitude of looking down upon a Dalit student emanates from a questionable criteria of merit.

Carol Upadhya in this paper ‘Employment, Exclusion and ‘Merit’ In the Indian IT Industry’ (2007) writes:-

“It hardly needs to be pointed out that the merit argument ignores the social and economic factors that produce ‘meritorious’ candidates in the first place, especially the continuing monopoly over a certain kind of cultural capital that is enjoyed by the middle class- which is composed mainly of upper castes – due to their greater access to the best educational institutions and other processes of social closure.”

Rohith found himself in a position where he had to stand trial by the society for his Dalit background, to justify his existence as a PhD student and to be questioned on his merit. He was not ready and could not bear anymore. The outcome of the investigation of Rohith’s suicide is obvious, rather known to us. In his suicide note, he has not blamed anyone for his death. This is a strong evidence in law and on this ground alone, each of those protagonists of caste system will go scot free who discriminated against him, alienated him from this beautiful world and drove him to suicide. He did fight back but gave up too early. It is not important whether he challenged ABVP or NSUI or SFI, what is important is that he fought against the mindset that pervades all of us.

”The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never was a man treated as a mind.”

Rohith wrote in his suicide note.

Comments

0 comment