views

New Delhi: On April 6, the Supreme Court of India invoked its power under Article 142 to validate all proceedings through video-conferencing — not only those which were to take place in future but also those which had already been conducted.

“All measures that have been and shall be taken by this Court and by the High Courts, to reduce the need for the physical presence of all stakeholders within court premises and to secure the functioning of courts in consonance with social distancing guidelines and best public health practices shall be deemed to be lawful,” stated the order of the three-judge bench, headed by Chief Justice of India SA Bobde.

The bench, also including Justices DY Chandrachud and L Nageswara Rao, added that “the Supreme Court of India and all High Courts are authorized to adopt measures required to ensure the robust functioning of the judicial system through the use of video-conferencing technologies.”

There is, however, some legal conundrums arising out of this order: Why did the Supreme Court have to pass an order under Article 142 to authorise itself to hold hearings through video-conferencing?

And if there was an impending need, can the Supreme Court use this power to ratify any act retrospectively? In essence, could the top court use its constitutional authority to say that not only what happens henceforth but also what has happened in the past is legally valid, bereft of any statutory and procedural limitations?

Additionally, can the Supreme Court pass a sweeping order under Article 142 with respect to unconnected proceedings, without even hearing the parties affected by the orders passed between March 23 (when the first hearing through video-conferencing took place) and April 6?

So, we come back to the moot question as to what was the need for the CJI-led bench to pass this ratifying order in a suo motu case under Article 142 after more than 10 days of resorting to hearings through video-conferencing due to the outbreak of Covid-19.

Indeed the times are difficult; challenges are new. But employing Article 142, which empowers the Supreme Court to issue all kinds of orders to do “complete justice”, has to be an exceptional and extraordinary exercise, to be carried out when existing provisions of law and procedure cannot adequately deal with a situation. Also, this exercise is usually done to introduce and effectuate a change, and not to certify certain events in the past.

It should be relevant to map out the judicial history of Article 142 and the scope of it as enunciated by the Supreme Court for a better understanding of ambit of this power and boundaries thereon.

In 1963, a Constitution Bench in Prem Chand Garg Vs Excise Commissioner, UP, Allahabad, held as: “An order which this Court can make in order to do complete justice between the parties, must not only be consistent with the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution, but it cannot even be inconsistent with the substantive provisions of the relevant statutory laws.”

This judgment also made a distinction between laws and procedure while ruling that a departure from the procedure could be made if it is necessary to do complete justice between the parties.

A nine-judge bench in Naresh Shridhar Mirajkar vs State of Maharashtra, (1967), and a seven-judge bbench in AR Antulay vs RS Nayak, (1988) endorsed this view.

Relying on these judgments, the apex court laid down in Arjun Khiamal Makhijani Vs Jamnadas C Tuliani, (1989), that Article 142 does not contemplate doing justice to one party by ignoring mandatory statutory provisions and there by doing complete injustice to the other party by depriving such party of the benefit of the mandatory statutory provisions.

However, a Constitution Bench, while deciding Union Carbide Corporation Vs Union of India in 1989, sought to emphasise upon the untrammeled powers of the top court as it held that prohibitions or limitations or provisions contained in ordinary law cannot, ipso facto, act as prohibitions or limitations on the constitutional powers under Article 142.

Again in 1993, Keshabhai Malabhai Vankar Vs State of Gujarat asserted that power under Article 142 was unbridled in its very nature.

But in Supreme Court Bar Association Vs Union of India, 1998, a Constitution Bench pressed for a balanced and guarded approach. This verdict clarified that constitutional powers under Article 142 cannot, in any way, be controlled by any statutory provisions, but at the same time these powers are not meant to be exercised when their exercise may come directly in conflict with what has been expressly provided for in a statute dealing expressly with the subject.

The court further observed that Article 142, even with the width of its amplitude, cannot be used to build a new edifice where none existed earlier, by ignoring express statutory provisions dealing with a subject and thereby achieve something indirectly which cannot be achieved directly.

In State of Punjab Vs Bakshish Singh, 1998, the top court reiterated this proposition. Again, in MC Mehta Vs Kamal Nath, 2000, the Supreme Court held that Article 142 cannot be pressed into service in a situation where action under that Article would amount to contravention of specific provisions of the Act.

A Constitution Bench in ESP Rajaram Vs Union of India, 2001, stated that power under Article 142 is not to be exercised in a case where there is no basis in law which can form an edifice for building up a super structure.

In crux, the ratio seems to be that the Supreme Court must exercise its powers under Article 142 only to deal with situations where existing provisions and prevalent rules cannot cater to the necessity of doing “complete justice”.

But this body of judgments is silent on the aspect whether Article 142 can be used by the apex court to authenticate some proceedings, which were conducted in absence of pertinent laws or rules to either approve them or prohibit them.

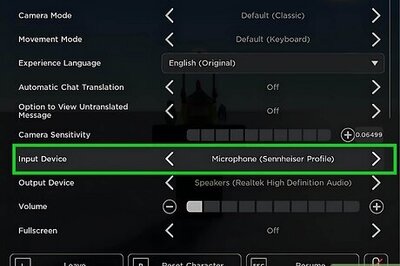

When the apex court resorted to video-conferencing, there was a vacuum of regulatory framework regarding the manner in which such hearings could take place. Norms were not clear as to who could appear, what all video and audio applications were permitted to be used or the ones restricted, recordings of these hearings and several pertinent aspects.

Notices and circulars were issued by the Supreme Court registry one after the other to indicate the manner which these proceedings had to take place. A standard operating procedure (SoP) has also been now laid down for conducting these proceedings. The new Supreme Court rules, however, are yet to be notified, registering officially these changes.

Judges are supposed to be the master of their courts and it is for them to decide the modalities of a hearing. In the absence of any statutory prohibition, they are free to conduct their courts in a manner they deem appropriate.

Thus, it was widely understood that all these proceedings through video-conferencing were legally valid although they were a completely new exercise, which hinged on extensive use of technology and connoted a paradigm shift from the age old practise.

It is, therefore, not clear what was the necessity for the Supreme Court to issue an order under Article 142 to validate these proceedings. Moreover, why should this order make a reference to the unconnected cases that had already been heard in the last 10 days? Why did the apex court have to say through a judicial order that it is “authorized” to use video-conferencing?

Abundant caution or doubt, be that as it may, but this could perhaps be a first when the top court exercised its power under Article 142 regarding cases that were not before it nor were the parties, affected by the orders in the past in distinguishable proceedings, present before it.

In one fell swoop, the Supreme Court has decided for cases not even listed, and perhaps also pre-empted any challenge to these proceedings in future.

Article 129 provides that the Supreme Court shall be a court of record whereof the judicial proceedings are enrolled for a perpetual memorial and testimony.

Such an elevated status warrants utmost caution and organisational checks before a major institutional change is brought upon. Article 142, as has been repeatedly asserted, cannot be used to do something indirectly which cannot be done directly.

It is now for those at the helm of judiciary to ponder whether the use of Article 142 was at all required.

Comments

0 comment