views

After some confusion and preemptive reportage, the Union Minister for Food Processing Industries, Harsimrat Kaur Badal, clarified late last night via Twitter that Khichdi is NOT going to be named India’s National Food at the upcoming World Food India showcase organized by her ministry. The confusion arose from the news that the country’s culinary eminence gris Chef Sanjeev Kapoor will be attempting a world record by cooking a staggering 800kg of khichdi. While a statement by the minister acknowledged that “khichdi is India’s wonder staple food”, her tweet makes it clear that khichdi isn’t going to be given the admittedly contentious title of ‘National Dish’. Buy why not? It’s not even that contentious.

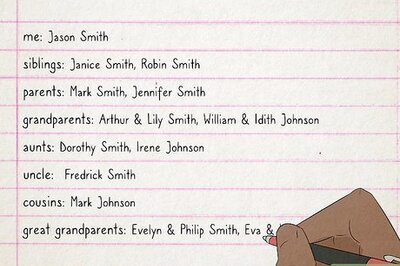

Delhi has Rajma Chawal (and Butter Chicken); Bengal its Maacher Johol and Poshto Everything; Kerala its Avial and Matta rice; the Sindhis their Kadhi. And we all have khichdi. It is perhaps the one dish that is ubiquitous across the country, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, as that hoary chestnut goes. Never exalted yet never ignored, khichdi is integral to the Indian experience. It’s one of the first solid foods many of us are fed, and remains a universal solvent for whenever we’re ill in body or mind.

The taste of dal, they say, changes every 20 miles you travel in India. All Indians, of course, know this is a fallacy. The taste of dal changes at every home you visit in the country; each household has its own preferred pulse, tadka, even exact manner of preparation. The same could be said of most dishes common to Indian diaspora, but none of them enjoy the same acceptability of the humble khichdi.

First, there’s its very composition: a conflation of and rice, pulses and lentils. No matter how it’s tempered (or as it often is, not), no matter whether the main dish or mainly an accompaniment, whether cooked in oil or clarified butter, its foundation always comprises rice and pulses and lentils (all lentils are pulses but not all pulses are lentils) - the two ingredients universal to Indian food, whatever that may entail. Rich in protein and carbohydrates, the dish provided abundant fuel for whatever task lay at hand, from the hoeing of fields to the courting of royalty in the past, and from filing information for an Aadhar card to filling in 9 hours of work at your office in the present.

Then is its flavor profile. The soft muddling of rice and pulses can stand alone as a soothing mains a la comfort food, or an ideal delivery vehicle for far bolder culinary creations, smoothly blending into the backgrounds of spicy or spiced.

No longer confined to homes, khichdi -- usually a syncretic version of it -- even finds place in restaurant menus now, as part of Modern Indian. If Chef Manish Mehrotra from Indian Accent first legitimized avant garde khichdi with his Kitsch-ree, a kedgeree composed of bacon bits, burnt garlic, nuts and chicken along with the rice and pulses, other restaurants soon ran with it, serving up dishes like Butter Chicken Khichdi, Italian Khichdi a la Risotto and robust, meaty Khichras.

Indeed, while khichdi’s non-vegetarian cousins in the North (Awadhi Khichra) and South (Hyderabadi Haleem, with cracked wheat in place of the rice) were clearly influenced by the Islamic conquest of the country - which began in the 10th Century – the original was recognized as an Indian staple from the times of Alexander the Great. Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the

court of Chandragupta Maurya, mentions a combine of rice and pulses that was savored by people all over the country.

That was more than 2200 years ago. And while so much has changed during that time, our love for khichdi surely hasn’t. So let’s call it our national dish already.

Comments

0 comment