views

In December 1954, two Bengali engineers made their way from Calcutta to the garden city of Letchworth in England. Mohi Mukherjee and Amaresh Roy were at the British Tabulating Machine Company’s workshop to observe the manufacture of the computer bound for India. The machine took six months to build, and they used the time to familiarize themselves with its processes, learning how to operate it. Once their training ended, they travelled through Europe to visit ‘computing machine laboratories’ and returned home in early 1956. India’s first digital computer followed them in two crates.

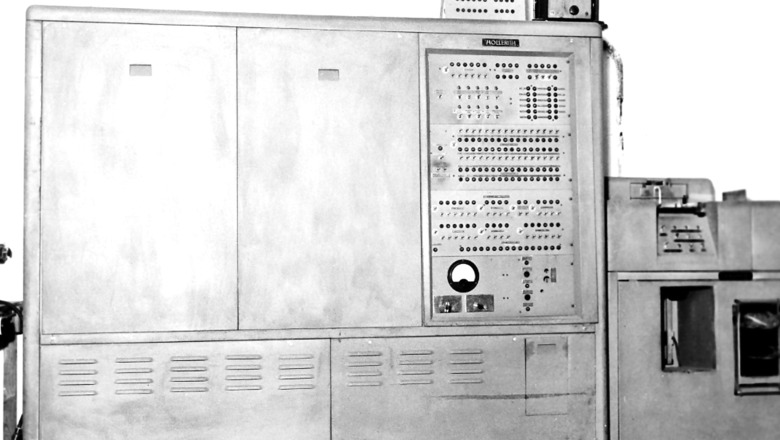

Ten feet in length, seven in breadth and six in height, the computer consisted of three vertical metallic cabinets. Given Calcutta’s humidity, it was housed in an air-conditioned room on the Institute’s campus. The HEC-2M could perform 200 additions or five multiplications per second, and it could only handle a total of nine digits. It took two months to install, and as it had arrived from England with no manuals, Roy and Mukherjee had to assemble it based on their notes, sometimes relying just on instinct. When, for example, the chainsmoking Roy realized that he needed a specific clearance between the sixteen tracks constituting the computer’s memory, he found that his trusted cigarette paper did the job just fine.

The computer wasn’t easy to use. Roy and Mukherjee arranged sessions to train other engineers at the Institute and soon created their own instruction manuals. Within months of being inaugurated, in March 1956, a dozen workers at the Institute’s Electronics Computer Laboratory had learned how to operate it. Over the preceding two years the number of engineers working at the laboratory had grown. Dwijesh Majumdar, for example, was drawn to the Institute after reading a newspaper report about Mahalanobis showing the analogue computer to Nehru. When they met, the Professor invited Majumdar to join the fledgling electronics laboratory, but not before delivering ‘a detailed lecture on the importance of computer[s] for developmental planning in India’.

Apart from processing National Sample Survey data and performing calculations for divisions within the Institute, the HEC-2M received numerous computational requests from scientific institutions across the country. Some of the most complex mathematical tasks that the computer was tackling, however, were ones submitted by the Institute’s Planning Division. As the first digital computer in India and one of the very few in Asia, it was also a tourist attraction for ministers and other dignitaries. But, as Mahalanobis had noted before its purchase, this computer was never going to meet the needs of the National Sample Survey and economic planning. It functioned ultimately as training wheels.

The Institute had also begun inviting computer experts from abroad to help with the considerably more ambitious project of building a digital computer on site. Begun in early 1954, the plan stumbled within months of having been announced. Talks with Soviet computer experts had given the laboratory pause; the Indian engineers realized that designing and constructing a new computer would take years. It made more sense to focus on operationalizing the British computer and simply acquiring another computer from abroad. Meanwhile, the deal that Mahalanobis brokered with the Soviet Union had jumped through bureaucratic hoops and met with approval. The Institute initiated a request to the United Nations, through New Delhi, for a Soviet machine.

The Ural — named presumably to evoke the mighty Russian mountain range — arrived in Calcutta only in late 1958, two years after it had initially been expected. The Soviet computer was formally handed over after a conference inaugurated by a member of the Planning Commission. The only two digital computers in South Asia were now in Baranagore, on the Institute’s campus. The Times of India reported that the new computer could work ‘600 times faster than a single man’. Eight Soviet engineers followed the massive computer, and it took them three months to install it in yet another air-conditioned room. Unlike the earlier British machine, this one arrived with instruction manuals. Unfortunately, they were in Russian. With the help of an interpreter, the Soviet engineers held classes on construction, operation and maintenance. Indian engineers also learned some Russian in order to follow the manuals. Soon the Ural was running two shifts a day, its printer generating ‘ridiculous sounds’. When not involved on tasks relating to the Institute’s priorities (sample surveys and planning), its time was contracted out to other universities and scientific institutions. By 1959, the Indian Statistical Institute had secured the only two digital computers in the subcontinent and served as the de facto national computation centre. It was apparent, however, that the Institute required even more computing power.

This excerpt from Planning Democracy: How a Professor, an Institute, and an Idea Shaped India by Nikhil Menon has been published with the permission of Penguin Random House India

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment