views

It’s not just Kautilya’s Mandala theory that makes Pakistan and China eternal enemies of Bharat. For the uninitiated, it must be reiterated that the Mandala theory, as explained in Arthashastra, makes it categorically clear that an immediate neighbour cannot be one’s natural friend or ally. They would be naturally susceptible to being upset and agitated, prone to gratuitous rivalry and one-upmanship, and bugged by an innate sense of jealousy even while sharing a similar ideological worldview. What further goes against Pakistan and China, in particular, is while the very raison d’etre of Islamabad’s existence is anti-India-ism—you remove it and the very rationale of that country’s very presence goes away—the latter is a pale shadow of its old, civilisational self, especially since 1949.

To confuse today’s China with the historic, civilisational China would be a blunder of epic proportions—something Jawaharlal Nehru compulsively committed during his 17 years as Prime Minister. The old China shared with Bharat a guru-shishya relationship, and not that of a geostrategic rival—as has been the case today. The difference between the two Chinas is so glaring that while the old one would fight battles with its neighbours to acquire knowledge—in fact, one Chinese ruler chose to invade a neighbouring state simply because the latter refused to part ways with a Sanskrit scholar—the post-1949 China has been obsessively fighting for land and resources. While the old China was hungry for knowledge, today’s China has had an insatiable appetite for power.

When one adds this genetic reorientation of China with communist doublespeak, the result is outright dangerous, to say the least. In 2012, Shyam Saran, former foreign secretary and one of the best minds on China in current times, narrated a story during a public lecture. Referring to a conversation between former Secretary-General, Ministry of External Affairs, RK Nehru, and Chinese Premier Chou En-lai in 1962, just before the big war, Saran said, “RK Nehru drew attention to reports that China was leaning towards the Pakistani position that Jammu & Kashmir was a disputed territory. He recalled to Chou an earlier conversation, where when asked whether China accepted Indian sovereignty over J&K, he had said rhetorically — has China ever said that it does not accept Indian sovereignty over J&K, or words to that effect. At this latest encounter, Chou turned the same formulation on its head, to ask: Has China ever said that India has sovereignty over J&K?”

This is today’s China, hegemonic, imperialistic and hypocritical. Seeing Nehru deal with this China as if he were dealing with a civilisational one, one realises how naïve and imprudent the first prime minister was in his dealing with Mao Zedong and his men, especially Prime Minister Zhou Enlai. One is well aware of Nehru’s Tibetan folly (forget about rallying the world against China’s invasion of Tibet, about which the US was extensively worried and agitated in the 1950s, Nehru’s India actually helped the PLA take over the Roof of the World by providing them with rice when they faced food scarcity up there). So has been the case with the Nehruvian rebuffing of the UN Security Council seat, saying China should get it first. Former foreign secretary MK Rasgotra in his 2016 book, A Life in Diplomacy, too exposed how Nehru refused then President JF Kennedy’s offer to take the American help to nuclearise India. Kennedy wanted democratic India to become the first nuclear power in Asia, beating communist China, but Nehru the idealist had other plans.

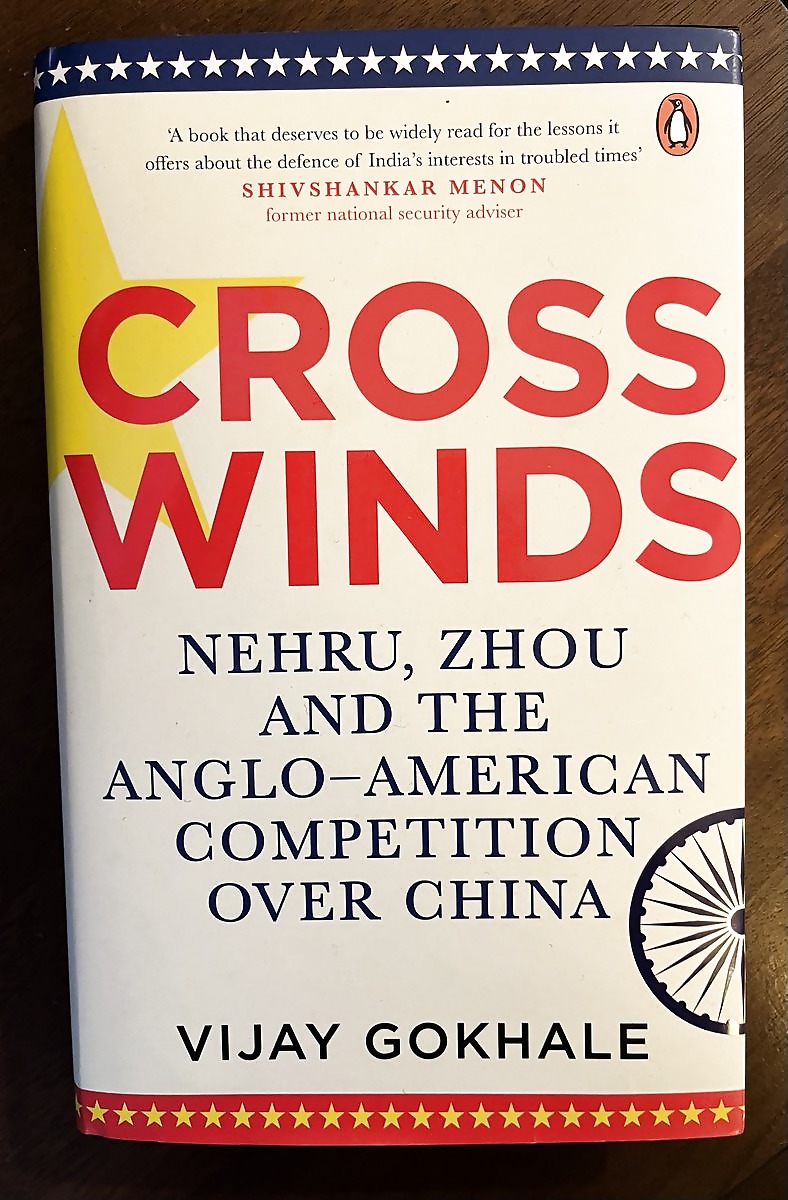

Now Vijay Gokhale has come up with a new book, Crosswinds, which provides another aspect of Nehruvian folly vis-à-vis China. Among other things, the book brings out quite eloquently the undue haste on the part of the Nehru dispensation to grant official recognition to Mao’s China, at Britain’s behest, and against the wishes of the United States. The book, in that way, can be said to be an extension of Gokhale’s previous work, The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate with India, which cites the hurried recognition of the communist state as one of the major diplomatic failures of the Nehruvian State.

While the previous book confines itself to explaining how Nehruvian India’s haste in recognising Mao’s China was a diplomatic naiveté, Crosswinds takes the narrative forward to let the readers know about the conniving role played by Britain in pushing Nehru towards recognising communist China at the earliest. This was against the American thinking which didn’t want India to recognise in a hurry. The feeling in the UK in the late 1940s grew that, writes Gokhale, “far from trying to create a joint Anglo-American policy on China, the US was paying scant attention to British interests when crafting its China policy”.

To add to it, Britain had by then realised that the US would not be able to stem the communist rise in China. Also, it could see the Chinese not joining the Soviet forces, thus the British dispensation, unlike its American counterpart, wasn’t particularly alarmed by Mao’s rise.

Writes Gokhale, “In May 1949, the British government advised other Commonwealth governments, including the Government of India, that while they watched and waited for the communists to make the first move, any appearance of ‘ganging up’ against them should be avoided. In the case of India, however, this was not a major concern for the British. Noel-Baker had reported to the cabinet that Nehru’s tendency was to ‘write down the menace from that direction (communists)’.”

Britain played both ways: To the Americans, it said that Nehru was too tied up internally to play any role in China. And to the Indians, it said that China was largely an American problem with which India should not get involved. To quote Gokhale again, “Britain understood well that if the US got India’s support for its China policy (which was to delay recognising the new communist regime), Nehru’s stature and capacity to influence other Asian states and the Commonwealth members could potentially jeopardise British interests in the Far East.”

Just before Nehru’s official US visit in 1949, the US Ambassador to India categorically told the Ministry of External Affairs that “there should be no haste in recognition (of the) regime”. Among the four reasons, one categorically asked New Delhi to seek “convincing evidence” from Beijing that “such recognition would result in marked improvement in India’s ability to protect its interests”. Interestingly, even when Nehru was on his official visit to the US, Britain left no stone unturned to convince India of the “correctness of the British position and to persuade India to follow suit”.

Britain, thus, played a sinister role in not just encouraging India to officially recognise Mao’s China in haste, but also created a deep wedge between New Delhi and Washington DC. One wonders how the Chinese saga would have unfolded had India not pursued the Nehruvian self-goal. Interestingly, as one ponders over this, a news report appears saying the Biden Administration has backed New Delhi on Arunachal Pradesh, calling the Northeastern state an integral part of India.

Winds are blowing again in Bharat’s favour. Its leadership must take advantage of this situation and let the country sail fast in the sea of development, strength and prosperity. Above all, new India must correct its notion of the enemy (shatru bhava). Even if the West may not have enough prerequisites to be Bharat’s ally, it is in the latter’s interest to create an honourable space for itself in the Western global order. As for the enemies, remember Chanakya’s Mandala theory and be wary of Pakistan and China: One is born out of anti-India-ism, while the other just cannot see itself excelling in a world order where Bharat is thriving. And, yes, the country must keep a healthy scepticism for anything coming out of the British island.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment