views

A storm in a teacup — this is the state of politics in Delhi. The issue is Prime Minister Narendra Modi visiting Chief Justice of India Dhananjaya Yeshwant Chandrachud’s residence on Wednesday evening for Ganpati Puja and performing aarti there. Be it opposition parties or activist-type advocates, everyone is up in arms over this. Questions have ranged from the end of “separation of power” to possible collusion between Modi and Chandrachud and the CJI delivering verdicts in the Centre’s favour due to their personal relations. From Congress, Shiv Sena (UBT), and Samajwadi Party leaders to senior Supreme Court lawyer Indira Jaising, all have attacked Modi and Chandrachud.

So the question is whether PM Modi has committed a sin by visiting CJI Chandrachud’s residence, or is Chandrachud’s impartiality at risk because Modi visited his house? An even bigger question is whether Chandrachud should have performed Ganpati Puja at home, and even if he did, was it appropriate for him to make it public with images of PM Modi’s arrival. Many such questions have arisen.

To find the answers, we will have to explore the past, because to look for what is not mentioned in the Indian Constitution, one has to go into conventions. The question is whether the Indian Constitution prohibits the Chief Justice from performing puja or participating in religious programmes. Under the interpretation of “separation of power” in the Constitution, is the meeting of the Prime Minister and the CJI, that too at the latter’s home illegal, or against conventions? Does constitutional decorum demand that the Prime Minister of the country not meet the CJI personally and the Chief Justice shouldn’t visit the PM’s residence either? And particularly not for religious functions? Does the Constitution say that, for the sake of being secular, a judge, especially the one sitting on the seat of the Chief Justice, should stay away from religious functions? Can’t the Prime Minister of the country get some personal advice from the CJI, because this will affect the latter’s impartiality?

It is unclear whether Modi or Chandrachud would answer all these questions after so much controversy. But the answer can be easily found when we look back at the times when neither was the BJP in power nor Chandrachud the CJI.

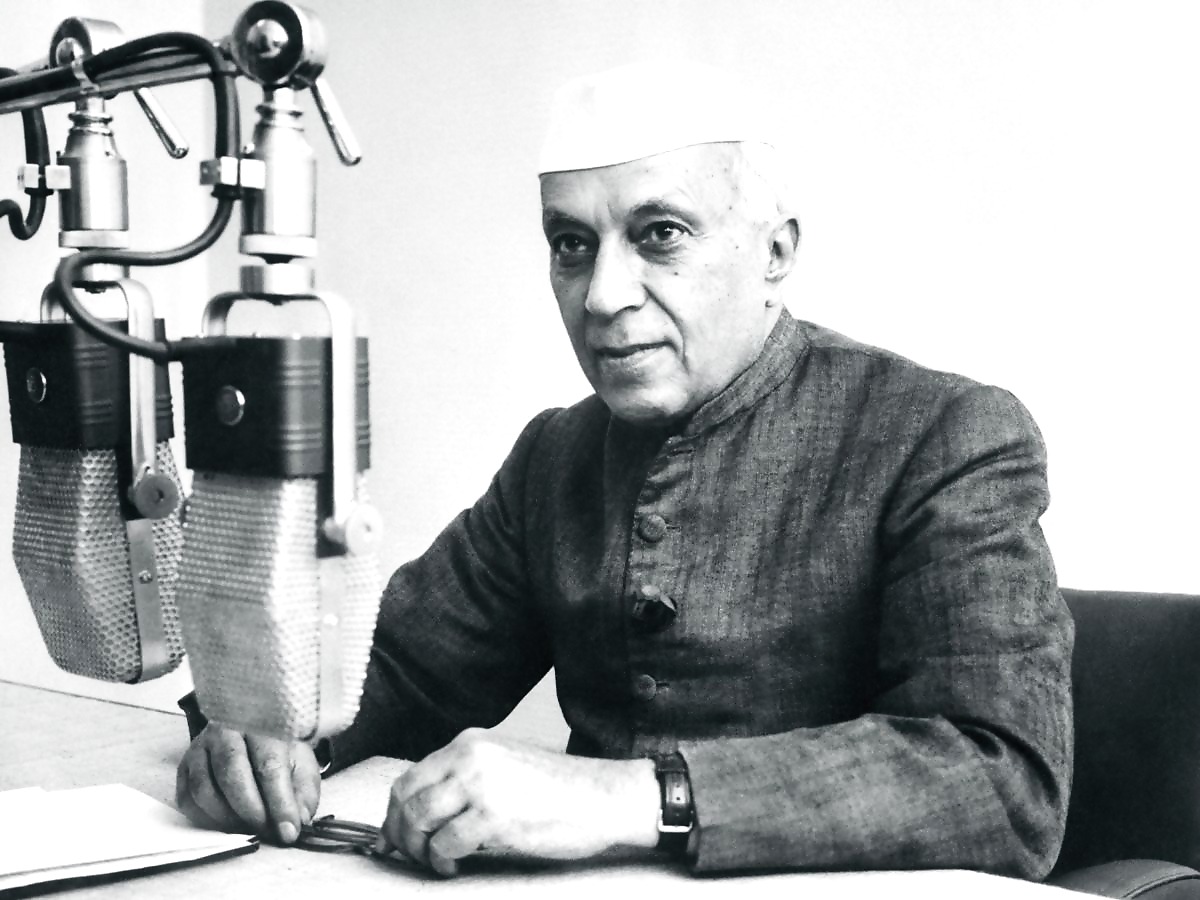

Nehru and Justice Gajendragadkar

The answers are recorded in the autobiography of Justice PB Gajendragadkar, who was the Chief Justice of India during the era of the country’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, which was published under the name To The Best of My Memory. Bear in mind that Nehru had appointed Gajendragadkar the CJI instead of Justice Syed Jafar Imam. According to convention and seniority, Justice Imam was to become the CJI when the then Chief Justice of India BP Sinha retired. But Justice Imam’s mental condition was such that Nehru could not make him the CJI even if he wanted to because the reports of expert doctors said that the judge, who used to fall asleep while hearing cases, could not retain any information and his mental state was so bad that he could not discharge the very important role of the Chief Justice of India responsibly.

In such a situation, as per the recommendation of Justice Sinha, Nehru made Justice Gajendragadkar the Chief Justice. Like the current CJI Chandrachud, Gajendragadkar was also a Marathi and religious. As Chief Justice, he had visited Tirupati and also participated in a programme at the Vithoba temple in Maharashtra.

In his autobiography, the judge said did not find any contradiction between the secularism enshrined in the Indian Constitution and his own religiosity. He said, “Having mentioned these two religious events, I ought to make it clear that, in my view, belief in true and rational religion was in no sense inconsistent with secularism. Secularism as it is understood in the West is basically and fundamentally anti-religion, anti-god and anti-church. On the other hand, our Constitution makes it clear that secularism means tolerance of all religions Important fundamental rights have been conferred relating to religion. The Constitution recognises that whereas some people may not believe in religion at all and yet they are entitled to all the rights of citizenship, others (and their number is legion) believe in religion and that does not affect their status as citizens. Some people seem to think that secularism means anti-religionism, but in my view that is not the Indian constitution’s concept of secularism at all. You may be non-religious, irreligious, or religious, you are a citizen all right, you have all the rights of a citizen, and, of course, you are subject to all the obligations, but religion as an institution is recognised in the Indian way of life and has been given a place of pride in the constitution with sufficient safeguards. Secularism merely means that no religion has the monopoly of religious wisdom. Our secularism is based on the principles laid down by the Bhagavad Gita:

येऽप्यन्यदेवता भक्ता यजन्ते श्रद्धयान्विता: |

तेऽपि मामेव कौन्तेय यजन्त्यविधिपूर्वकम् ||

which means that even the devotees of other gods who worsmp with full of faith, they also worship Me, O son of Kunti, though contrary to the ancient rule.”

Gajendragadkar has given his own example of following religion and participating in religious programmes and has not considered any contradiction between the Indian Constitution, secularism, and being religious. Those who criticise Modi and especially Chandrachud should at least carefully understand and consider the words of a philosophical judge like Gajendragadkar. If they do so, then they will not find any fault in either Chandrachud or Modi, if Chandrachud installed Ganpati in his house and Modi visited on the occasion of that puja. It should also be kept in mind that Bal Gangadhar Tilak himself had emphasised Ganpati worship and the establishment of pandals as a fight for Indian independence, and had made it a big weapon against the British.

In such a situation, questions arise on the intentions of those who cast doubts on Chandrachud’s impartiality because of the Ganpati puja and Modi’s participation in it. If we look at the judicial history after Independence, especially the relations between the Supreme Court judges and the prime ministers of that time, then both Modi and Chandrachud will appear to be saints. Leave aside raising questions on participation in a religious programme, the leaders of the INDI Alliance should remember that during the ten-year rule of the UPA when Manmohan Singh was the prime minister, he would always invite the then CJI to iftar parties. No one raised any questions at that time.

The history of the Nehruvian and Indira eras before Manmohan Singh is even more sensational and controversial. Many prime ministers even tried to get personal favours from the judges of those times and tried to put pressure on them. Meeting at home and visiting was a small matter.

Gajendragadkar himself has mentioned in his autobiography that Lal Bahadur Shastri, who became the Prime Minister after Nehru, whose morality and sense of purity in public life can hardly be questioned by anyone, even that Shastri used to invite Gajendragadkar, who was holding the post of CJI, to his home. Gajendragadkar writes very candidly in his autobiography that once Shastri ji said that he wanted to sit with him and have food at home, with his wife, without any formality, to discuss some important topics. Gajendragadkar agreed and had food with Shastri. Should this mean that Shastri violated the principle of separation of power? Or was Shastri trying to influence Gajendragadkar when he was the Chief Justice and proposed to make him the High Commissioner of India to Britain after his retirement? Clearly, the opposition of that time was neither this irresponsible nor shallow. Gajendragadkar writes that during that period, the then home minister used to visit his house regularly, as he lived right in front of the official residence of the CJI.

Gajendragadkar, sitting on the seat of the Chief Justice of India, used to visit the residence of the then PM Shastri in the dark of the night so that they could sit comfortably and discuss important issues and not have to wait. Imagine, if in today’s times, home minister Amit Shah goes to Chandrachud’s house or Chandrachud goes to meet PM Modi at night, how clamorous would the reaction of the opposition or activist-type advocates be, and would they not claim that something was a little fishy, or rather very fishy?

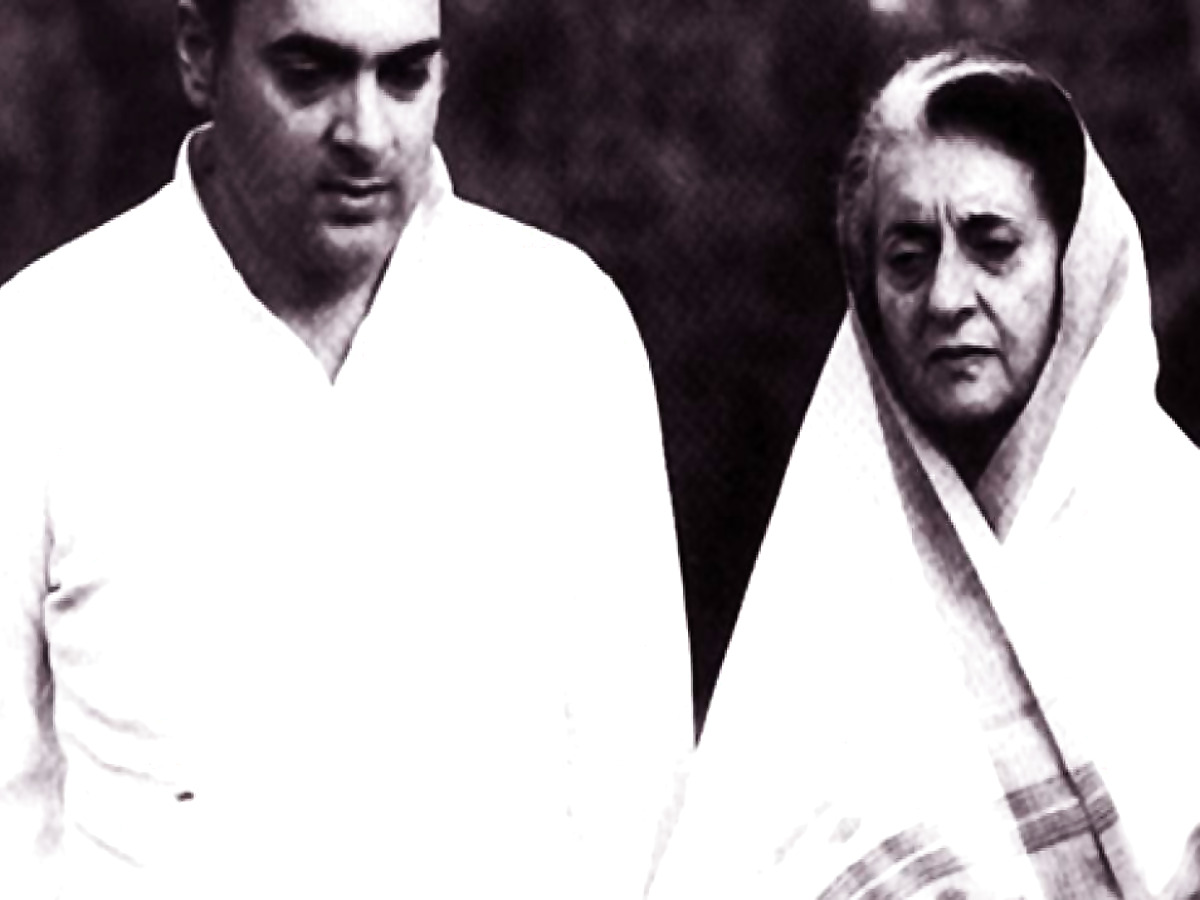

The Indira Era

However, such stories of the rapport and regular meetings between Gajendragadkar and Shastri will seem very boring and tame when you hear and learn about the stories from the Indira era.

There are thousands of such stories recorded in the book and diary of Professor George H Gadbois, an American who has researched the Indian judiciary and Supreme Court for nearly five decades, which will shock you. It would seem that Chandrachud and Modi both are very spiritual and pious people, by nature and actions.

Who can forget that for the first time in the history of the Supreme Court, ignoring three senior judges, the then prime minister Indira Gandhi decided to make Justice AN Ray, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, not because these three judges were mentally unstable like Justice Imam, whom Nehru was forced to sideline and make Gajendragadkar the Chief Justice. The truth was that after the retirement of then Chief Justice SM Sikri, Justice Ray was picked as his successor by the Indira government, ignoring the three senior judges, Justice Shelat, Justice Hegde, and Justice Grover. The reason for this was that these three judges had given a decision in the Basic Structure case, going against the government’s stance. The same “basic structure” for which today’s opposition tries to portray itself as a protector to promote its politics.

Even justifying this highly unethical act of Indira Gandhi in Parliament with complete brazenness, her close associate and minister of state for steel and minerals S Mohan Kumaramangalam had said that the way the judiciary had adopted a path of confrontation with the government in the Golaknath to Bank Nationalisation, Privy Purse and Kesavananda Bharati cases, Justice Ray was expected to steer clear of it. Those who are raising a hue and cry today over the separation of powers and impartiality of judiciary will hardly remember this incident. Needless to say, Justice Ray, like an obedient child, wholeheartedly supported Indira Gandhi and her government, and even decided to constitute a large constitutional bench without any demand to review the Basic Structure Judgment, which had to be dissolved immediately due to opposition from fellow judges. This judge, Justice Ray, was so extraordinary that when a tribute ceremony was organised in the Supreme Court as per tradition after his death, Ram Jethmalani said, “O Lord, do not send such a judge to this earth again”.

An even more serious and curious story is of Justice SC Roy, who was the nephew of West Bengal’s first chief minister, Congress leader and Nehru’s close friend Dr BC Roy. Just before the 1971 Lok Sabha elections, Indira Gandhi had asked him to move to the Supreme Court to help her. Like Nehru and Bidhan Chandra Roy, Indira Gandhi and SC Roy were also friends. Accepting the request of his friend Indira, SC Roy agreed to come to the Supreme Court. Before the appointment, he met the then law minister Gokhale, Kumaramangalam, and Siddhartha Shankar Ray and after this meeting, Justice Roy was appointed to the Supreme Court. After that, Indira Gandhi handed over the legal work related to her family property in Allahabad to Justice Roy and also gave him the related documents. The circumstances were such that in November 1971, Justice Roy died of a heart attack and Indira Gandhi quickly moved all the documents present in his house, so no one else would find out anything. This story was narrated to Professor Gadbois by Justice Roy’s wife herself.

Just like Justice Roy and Justice Ray, the story of Justice MH Beg is also very interesting. He was made the Chief Justice of India by sidelining Justice HR Khanna only because he had supported the government along with Justice Ray in the ADM Jabalpur case and Justice Khanna was the only judge who gave a dissenting judgement. Therefore, instead of Justice Khanna, who was the most senior after Justice Ray, Indira Gandhi picked Justice Beg and made him the CJI. Modi did not supersede a single judge of the Supreme Court in his ten-year tenure, but despite this, the opposition feels that he is the biggest threat to the impartiality of the judiciary.

The story of Justice Baharul Islam is the most controversial example of the unethical nexus between politics and the judiciary and giving preference to personal relations over judicial impartiality. This gentleman was a key Congress leader from Assam; before becoming a judge in the Guwahati High Court, he had held many positions in the Congress. After retiring as the Chief Justice of the Guwahati High Court, he became a judge in the Supreme Court, and after retiring from the Supreme Court, he again became a Congress leader.

Between 1952 and 1972, Islam continued to play a major role in Assam Congress. In April 1962, he went to the Rajya Sabha on a Congress ticket. In 1967, he contested the Assam assembly elections and, after losing, he was again sent to the Rajya Sabha in 1968. In January 1972, Indira Gandhi made him resign from the Rajya Sabha and instituted him as the first Muslim judge of the Guwahati High Court and then Chief Justice of the High Court as well. After his retirement from the High Court in March 1980, Congress tried to send him to the Rajya Sabha independently by supporting him. When that was not successful, nine months after his retirement from the High Court, he was made a judge of the Supreme Court. In this way, the Congress, using Baharul Islam, created a new record in the apex court, of making someone the oldest person to be a Supreme Court judge. When Islam became a judge on December 4, 1980, he was about 63 years old. Islam himself had accepted that he became a Supreme Court judge due to the grace of P Shiv Shankar, the then law minister in the Indira Gandhi government.

Matters came to a head when Islam resigned from his post just six months before his retirement as a judge from the Supreme Court and became a candidate from the Barpeta Lok Sabha seat of Assam at the behest of the Congress high command. Justice Islam, who was a favourite of the Congress, had participated in the bench just before his retirement which had given relief to the then Congress chief minister of Bihar Jagannath Mishra in a case of fraud. The extent of the Congress’s beneficence towards Islam can be gauged from the fact that when elections could not be held in Barpeta due to unrest, the party sent him to the Rajya Sabha in June 1983. Those attacking Modi and Chandrachud by crying about the separation of power should remember this incident.

Rajiv continued legacy

There are hundreds of such cases which reveal that the then Congress governments appointed judges even in the Supreme Court on the basis of personal loyalty, relations, vote bank, and allegiance. Who can forget the story of Justice M Fathima Beevi, who was made a judge of the Supreme Court long after her retirement from the Kerala High Court, merely to appease the vote bank, bypassing the country’s first woman High Court Chief Justice Leila Seth. Justice Seth herself has narrated this story. This feat was also the work of the Congress government led by Rajiv Gandhi, on October 6, 1989. The opposition will deliberately not want to remember all these stories, otherwise the challenge to Modi and Chandrachud will be blunted.

In fact, this attack on Modi and Chandrachud is an example of the joint strategy of the opposition and activist lawyers, who are adamant that the Supreme Court give verdicts in their favour in every case. These were the same leaders and lawyers who thought Justice Ranjan Gogoi was a hero when he held a press conference with his fellow judges against the then Chief Justice Dipak Misra, which was presented as their anger against the Modi government. But when Modi made the same Justice Gogoi the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and later sent him to the Rajya Sabha, he became the biggest villain for the alliance of the opposition and activist lawyers. The same thing happened with Justice SA Nazeer, who cleared the way for the construction of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya through a unanimous decision in the Ram Janmabhoomi case. When the Modi government made him the governor of Andhra Pradesh after his retirement in January 2023, the opposition and activist lawyers raised a hue and cry and accused him of being sold out to the Modi government. While making these allegations, they did not remember the past when Nehru had announced the appointment of sitting Supreme Court judge Justice Fazl Ali as the next governor of Odisha. Fathima Beevi herself was appointed the governor of Tamil Nadu by the HD Deve Gowda government in 1997. Modi was also opposed when he appointed retired Chief Justice of the Supreme Court P Sathasivam as the governor of Kerala in September 2014.

Modi and Chandrachud are following the same traditions which have been around for a long time. The Indian Constitution does not say anywhere that the heads of the executive and the judiciary will not meet each other, or will not visit each other’s homes. Those who oppose in the name of opposing are only lowering their own credibility, not causing any harm to Modi and Chandrachud.

Comments

0 comment