views

Whoever it was who coined the cliché of elections being a festival of democracy must be cringing every time it is repeated. Especially when it is meant literally. Like the political parties in Punjab who wrote to the Election Commission asking for elections to the Vidhan Sabha to be postponed because their voters, they felt, would be leaving for Varanasi for the Guru Ravidas Jayanti. Or a group in Manipur which wants elections moved from a Sunday because the community has to attend mass in church.

In a country where politicians regularly invoke religion to win votes, it is not surprising. In a way, India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had predicted it when he had said that free India would redeem its pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. Translation: you can trouble voters every day except on a holiday.

He couldn’t have imagined the holidays ballooning to the number we have now. The list of central government holidays announced for 2022 by the Department of Personnel and Training has 14 compulsory holidays plus three out of 12 optional holidays. Add to it 52 weekends and you get the picture.

India is a functioning democracy, yes, except when it is on holiday.

So whether it is Durga Puja in West Bengal or Ganesh Chaturthi in Maharashtra, woe is the official who tries to make the devotee into a voter especially when politicians are determined to turn the voters into worshippers (of themselves and their Gods).

Former Chief Election Commissioner SY Quraishi doesn’t see anything wrong in changing the schedule for festivals, saying the voters’ convenience is the overriding consideration. “If something is pointed out later, it can be accommodated if it doesn’t disturb the schedule, especially the end date,” he says.

In West Bengal, Durga Puja has long been a bone of contention between political parties, with the BJP accusing TMC of politicising puja pandals. But remember even the Marxists had adopted the pandals, transforming the celebrations from purely religious to essentially cultural, something that even UNESCO has now acknowledged by giving the Durga Puja of Kolkata the status of intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

In Maharashtra, Bal Gangadhar Tilak recognised the celebration of Ganesh Chathurthi as a means of political activism to fight the colonial ban on public assembly. Politics and religion have been intertwined longer than we think.

Pankaj Tripathi’s paramilitary officer in-charge of voting in the 2017 movie Newton put it best when he described the voting officers as a Ramlila mandli (troupe) in elections that are clearly shown as a theatre of the absurd.

Perhaps Sukumar Sen, the first Election Commissioner of India, was right when he described the first General Election as “the biggest experiment in democracy in human history”. Or perhaps the much-respected editor of the Tamil daily Swadesamitran, CR Srinivasan, was correct in dismissing “the whole adventure” (as in the elections) as the “biggest gamble in history”. How could a nation, where a mere 15% of the population was literate, survive as a democracy founded upon the principle of universal adult suffrage?

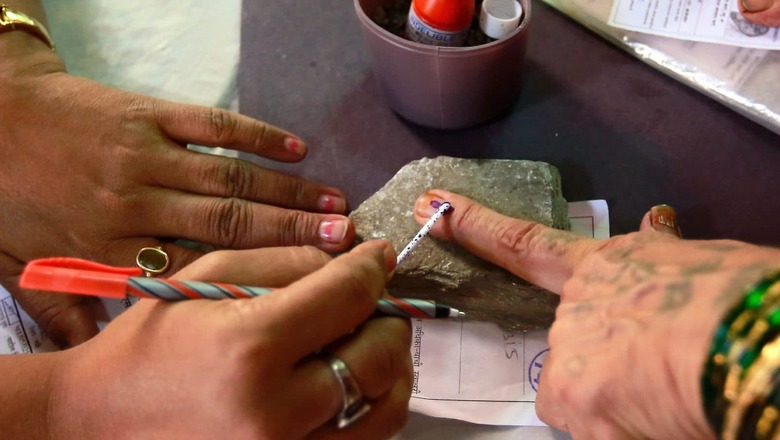

Srinivasan was proved wrong, as were many other doomsday prophets, by the 106 million people (out of the 176 million eligible to vote) who exercised their right guaranteed by Article 326 of the Constitution to elect 489 Lok Sabha MPs and 3,280 members of the state Legislative Assemblies.

The election process officially began on October 25, 1951, at a remote Buddhist village named Chini in the present-day Kinnaur district in Himachal Pradesh. Votes were cast first in this Himalayan state before the onset of the winter, when it would be rendered inaccessible because of heavy snowfall and inclement weather. The rest of India voted in February and March 1952, in what historian Ramchandra Guha has called an act of faith. The First Lok Sabha was constituted on April 17, 1952.

Since then, we’ve had 17 General Elections in a country with 1.2 billion population and around 900 million voters.

Which reminds me it’s the 70th anniversary of India’s first General Election. Isn’t that yet another occasion to celebrate? Let the festivities begin.

The author is a senior journalist and former editor of India Today magazine. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment