views

Few contrasts could be starker than the sandy, brown landscape of the Thar dotted with camels and chinkaras, when juxtaposed against the cold, white expanse of western Greenland where surface transport is still largely by husky sledges. The two regions have little in common, but not for Mike ‘Sniffer’ Watts.

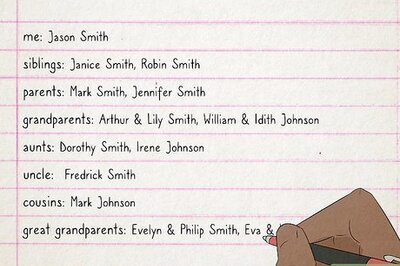

In the oil industry, they don’t call him ‘Sniffer’ Watts without reason. The 53-year-old exploration chief of Cairn Energy and his team discovered black gold deep inside the desert sands of Barmer in Rajasthan, when few were willing to explore the region. Till 2003, Rajasthan had hardly been explored. In fact, Cairn had bought the block that now contains Mangala and 16 other oil fields from Shell for a paltry $7 million. Today, with over a billion barrels of proven reserves, the field in Barmer is the country’s biggest find in over two decades and is among the top 100 fields in the world.

Thanks to the discoveries in India, Cairn moved from being a small Scottish oil explorer to become one of the most valuable oil and gas companies in the UK. And Watts and Bill Gammel, the chairman of Cairn Energy, are now using the success and credibility earned in Rajasthan as a springboard to bid for bigger projects that would have earlier been out of its purview.

“We have built a tremendous knowledge and expertise of developing oil fields in Rajasthan and this is transferable to other parts of the world,” says Watts.

That’s how he landed in Greenland last year and is now shooting seismics in the icy basins of the Subarctic. It’s one helluva bet. Gammel has already been quoted in The Scotsman saying that Greenland could offer a structure that is five or ten times bigger than Mangala.

But like all frontier exploration forays, it carries enormous risks. Environmental groups are closely monitoring the oil industry’s activities in the Arctic. The ice caps are melting and there is fear that drilling could hasten the process.

The Gammel-Watts duo is, of course, taking care to carry the local Greenlanders with them. Community meetings have been organised to address any concerns. Simultaneously, in the last two years, building on their lessons from Rajasthan, they’ve gradually put in place all the critical elements.

One, they’ve created Capricorn, named after Bill Gammel’s sun sign, as a separate exploration arm. (Industry talk suggests that Gammel delayed Capricorn’s listing because of a potential upside of the Greenland asset). As Capricorn’s CEO, Watts will lead the Greenland exploration drive.

Two, a part of the Rs. 29,200 crore that is estimated to flow from the fields in Rajasthan till production plateaus in 2014 will be spent on exploration in areas like Greenland and possibly oil-fields in strife-torn Iraq. By August, Capricorn will be ready with its drilling programme. This March, Cairn Energy raised about $160 million by placing 5 percent of its equity with institutional investors. The funds will be used in Rajasthan as well as to accelerate exploration in Greenland.

Three, in Rajasthan, there were moments when things looked hopeless. The company had to keep the faith even after drilling 15 wells without any viable oil find. “It was sometimes difficult to convince our colleagues on the board on why we had to go on, when there is little to show for the drilling. But we learned one thing from our Rajasthan experience: You’ve got to have staying power when you are convinced about the geology of a region,” says Watts.

Watts began his career with Big Oil when he joined Shell in 1980. But for high-risk, early stage exploration, Cairn has little in common with firms like Exxon, Shell and Chevron. It looks for less-explored geological arenas. “Rewards are lower in discovered areas, because we are left looking for crumbs that others may have missed. Early entrants, on the other hand, are often successful,” says Watts.

However, in a shrinking world, unexplored terrains are difficult to find.

PAGE_BREAK

Ironically, it was global warming and withdrawing ice that exposed oil-seeps in Greenland. A May 2008 US Geological Survey study concluded that the Arctic could contain as much as 13 percent of the world’s ‘yet to find’ oil and 30 percent of its undiscovered gas.

The Greenland Bureau of Minerals and Petroleum’s invitation to auction off blocks attracted bids from several oil majors.

Most oil operators in the area are North American players like ExxonMobil, Chevron, Encana, Husky oil and the Greenland national oil company, Nuna Oil. Over the past two years Capricorn has steadily built up its position to six blocks (close to 52,000 square kilometres), making the region one of the biggest bets for the company.

It acquired about 10,000 kilometres of seismic data last summer, which is being reviewed for signs of hydrocarbon. The company is also gearing up to participate in future bid rounds coming up at Baffin Bay and north-eastern Greenland.

“We are funded for the initial drilling programme. At a cost of about $150 million a year [it] is well within our means,” says Watts. “If we find something, the big decision will be on development, which can run into billions of dollars.”

In an oil-field’s lifecycle, most of the investment comes in after oil is discovered, in what is called the development phase. During this phase, oil has to be extracted and pipelines laid to transport it to the nearest port or customer. This is when Capricorn plans to bring in bigger partners, to put in the equity.

“In this game, ability to raise money depends on when you blink. After a discovery, the longer a company carries on its own, the better the valuation it can get since the provenance of oil is better established,” says Watts. Capricorn Energy has obviously been structured with this in mind. As of now, Cairn Plc has a 90 percent stake in the company, while oil and gas investment company Dyas BV has picked up the remaining 10 percent. Capricorn could eventually be spun off as a separate venture. The structure allows Cairn Plc to play the role of a serial entrepreneur specialising in finding oil and gas.

However, hard realities of the slowdown have impacted some plans. On the exploration front, work on some blocks in the Mediterranean has been deferred to 2010. Greenland, though, continues to be top priority, says Watts.

Some Cold Facts

The picture on risk-taking ability is varied in the oil business. Many Big Oil companies choose to operate where the presence of oil is certain--the accent is on using technology to go further to get to known reserves. Jeff Waterous, chairman of Global Union Energy Ventures, an oil and gas focused investment bank, says one of the reasons is that Big Oil’s decisions are driven by the pressure to deliver quarterly results. It is easier to acquire oil-producing assets in discovered fields, even if it is at a higher price.

Yet, Big Oil is not completely missing in the Arctic. In a record lease sale last year Royal Dutch Shell Plc paid $2.1 billion for exploration blocks in the Chukchi Sea, off the coast of Alaska.

PAGE_BREAK

“High-risk projects are also often the ones with highest potential,” says Calgary-based oil-entrepreneur Chayan Chakrabarty, promoter of Bengal Energy. But production (especially from onshore fields) can often be six to seven years after a discovery is made. Raising funds can be tough if the portfolio is not balanced between exploration and production.

In Greenland, Capricorn has its job cut out. “With the available information, the blocks in Greenland look like a 5 to 8 percent success today. After interpreting data, this could go up to 10 percent. That is good enough for wildcat exploration,” says Watts. The flipside: A 90 percent chance of reaching a dry hole.

Oil industry analysts are, of course, questioning the wisdom of drilling in the Arctic after the fall in crude oil prices. The price of drilling and sustaining extraction of oil in the region is huge.

Experts from Cambridge Energy Research Associates (Cera), a Massachusetts-based global energy research firm, says that oil from the Arctic is justifiable at $100 a barrel, but it is difficult to profit if prices hold lower.

For the Greenland operations to be profitable, Capricorn needs oil prices to be above $40 a barrel. With demand falling with the slowdown worldwide, there are indeed only a few takers in the market for any bets on the Arctic frontiers.

Watts has a simple answer to folks who argue about his operation’s viability: He says being contrarian is all about taking positions that no one can understand at the moment. “Our estimate is that oil prices will be back firmly above $40 a barrel in five or six years. Supplies are unlikely to meet growing demand in the long run,” he says. Even so, he admits that drilling in the Arctic will be far more expensive than say in onshore Rajasthan. The cost of sinking one well in offshore Greenland could go up to $50 million to $60 million. In Rajasthan, he could knock off the same thing for $6 million. But then that’s perhaps par for the course for risk-takers like Watts.

Find this article in Forbes India Magazine of 03 July, 2009

T Series, The Bootleg Baron

Dog Sense Jingle Jungle

You Don’t keep a Dog and Bark too

Comments

0 comment