views

X

Research source

Going into the test, you will need strong background knowledge of the time periods and geographical areas on which you will be tested. Your documents will always relate back directly to the major subjects and themes of your class. The key to success is to analyze the provided documents and use them to support an argument in response to the essay prompt. While DBQ tests are rigorous, they allow you to actually do historical work instead of merely memorize facts. Don’t stress, put on your historian hat, and start investigating!

Analyzing the Documents

Review the documents for 10 to 15 minutes. If you’re taking an AP exam, you’ll have 15 minutes to review the prompt and document. During this initial reading period, you’ll carefully read the essay prompt, analyze the included documents, and develop your argument. For an AP exam, you’ll then have 45 minutes to write your essay. Exact times may vary for other exams and assignments but, for all DBQ essays, document analysis is the first step. For an AP exam, you will also need to include a thesis, set the prompt’s historical context, use 6 documents to support an argument, describe 1 piece of outside evidence, and discuss the point of view or context of at least 3 of the sources. Label these elements as you review and outline so you don’t forget something.

Identify the prompt’s keywords and assigned tasks. Ensure you understand what evidence to look for in the documents and what your essay needs to accomplish. Circle or underline task-oriented words such as “evaluate,” “analyze,” and “compare and contrast.” Additionally, note keywords such as “social,” “political,” and “economic,” as well as information regarding the time period and society in question. A prompt might ask you to analyze or explain the causes of a historical development, such as, “Explain how the Progressive Movement gained social, political, and cultural influence from the 1890s to the 1920s in the United States.” You might need to use primary sources to compare and contrast differing attitudes or points of view toward a concept, policy, or event, such as, “Compare and contrast the differing attitudes towards women’s rights in the United States from 1890 to 1920.” Keywords in these examples inform you how to read your sources. For instance, to compare and contrast differing attitudes, you’ll need to identify your sources’ authors, categorize their points of view, and figure out how attitudes changed over the specified period of time.

Note your documents’ authors, points of view, and other details. Read the sources critically instead of simply skimming for information. For each document, identify the author, their audience, their point of view, who and what influenced them, and their reliability. Underline key phrases and take notes in the margins, and refer to your notes when you write your essay. Suppose one of the documents is a suffragette’s diary entry. Passages in the entry that detail her advocacy for the Women’s Rights Movement are evidence of her point of view. In contrast, another document is newspaper article written around the same time that opposes suffrage. A diary entry might not have an intended audience but, for documents such as letters, pamphlets, and newspaper articles, you’ll need to identify the author’s likely readers. Most of your sources will probably be written documents, but you’ll likely encounter political cartoons, photographs, maps, or graphs. The U.S. Library of Congress offers a helpful guide to reading specific primary source categories at https://www.loc.gov/teachers/usingprimarysources/guides.html.

Place your sources into categories based on the essay prompt. Determine how each document relates to your prompt, and figure out how to use the sources to support an argument. For instance, if you’re comparing and contrasting differing attitudes, categorize your sources based on the opposing ideologies they represent. Suppose you have a letter sent from one suffragette to another about the methods used to obtain the right to vote. This document may help you infer how attitudes vary among the movement’s supporters. A newspaper article depicting suffragettes as unpatriotic women who would sabotage World War I for the United States helps you understand the opposing attitude. Perhaps other sources include a 1917 editorial on the harsh treatment of imprisoned suffragists and an article on major political endorsements for women’s suffrage. From these, you’d infer that 1917 marked a pivotal year, and that the role women played on the home front during World War I would lead to broader support for suffrage.

Think of relevant outside information to include in your essay. For an AP exam, you’ll need to include at least 1 piece of evidence beyond the provided documents. Rather than merely make a reference, you’ll need to describe how that event, policy, publication, person, or other piece of historical evidence supports your claims. For instance, perhaps you read that the National American Woman Suffrage association (NAWSA) made a strategic shift in 1916 from focusing on state-by-state suffrage to prioritizing a constitutional amendment. Mentioning this switch to a more aggressive strategy supports your claim that the stage was set for a 1917 turning point in popular support for women’s suffrage. When you think of outside evidence during the planning stages, jot it down so you can refer to it when you write your essay. A good spot could be in the margin of a document that relates to the outside information.

Developing an Argument

Review the prompt and form a perspective after reading the documents. After you’ve learned more on the topic, return to the prompt and come up with a response. Keep in mind you’re not simply forming an opinion based on gut instincts. Use the information you’ve gleaned from the documents to form a well-reasoned opinion supported by evidence. For example, after reviewing the documents related to women’s suffrage, identify the opposing attitudes, how they differed, and how they changed over time. Your rough argument at this stage could be, “Those in opposition saw suffragettes as unpatriotic and unfeminine. Attitudes within the suffrage movement were divided between conservative and confrontational elements. By the end of World War I, changing perceptions of the role of women contributed to growing popular support for suffrage.”

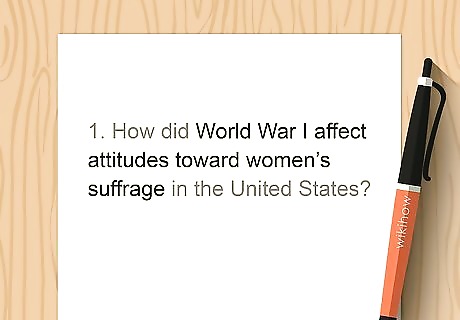

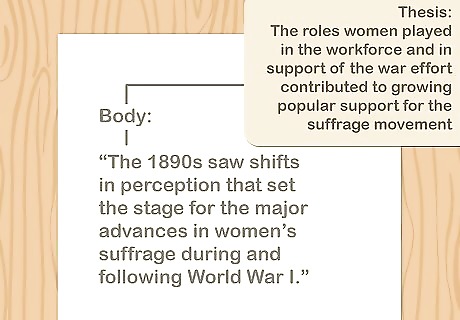

Refine your rough argument into a tentative thesis. A thesis is a concise statement that encapsulates your argument. Be sure that your thesis is a defensible claim that responds to the prompt, but doesn’t simply restate it. Suppose your DBQ is, “How did World War I affect attitudes toward women’s suffrage in the United States?” A strong tentative thesis would be, “The roles women played in the workforce and in support of the war effort contributed to growing popular support for the suffrage movement.” A weak thesis would be, “World War I affected how Americans perceived women’s suffrage.” This simply restates the prompt.

Make an outline of your argument’s structure. Start with your tentative thesis, then list roman numerals (I., II., III.) or letters (A., B., C.). For each numeral or letter, write a claim, or a step in your overall argument. Under each claim, list a few bullet points that support that part of your argument. For example, under numeral I., write, “New Woman: perceptions shift in the 1890s.” This section will explain the 1890s concept of the New Woman, which rejected traditional characterizations of women as dependent and fragile. You’ll argue that this, in part, set the stage for shifting attitudes during and following World War I. You can start your planning your essay during the reading portion of the test. If necessary, take around 5 minutes out of the writing portion to finish outlining your argument.

Plug your document citations into the outline. You must support your argument by citing the documents included in the prompt. For a quick reference, make notes in your outline where you’ll discuss a source. If you’re taking an AP exam, you’ll need to include 6 out of the 7 documents, so it’s important to stay organized. For instance, under “I. New Woman: perceptions shift in the 1890s,” write “(Doc 1),” which is a pamphlet praising women who ride bicycles, which was seen as “unladylike” at the time. Beneath that line, write “(Doc 2),” which is an article that defends the traditional view that women should remain in the household. You’ll use this document to explain the opposing views that set the context for suffrage debates in the 1900s and 1910s.

Refine your thesis after making the outline. Go back and make sure that your argument structure and supporting evidence indeed support your tentative thesis. Double check that your thesis is clear, doesn’t include any fluff or unnecessary words, and completely responds to the prompt. Suppose your tentative thesis is, “The roles women played in the workforce and in support of the war effort contributed to growing popular support for the suffrage movement.” You decide that “contributed” isn’t strong enough, and swap it out for “led” to emphasize causation.

Drafting Your Essay

Keep your eye on the clock and plan your time strategically. If you’re taking an AP exam, you’ll have 45 minutes to write your DBQ essay. Times may vary in other settings but, in any case, plan out how much time you can spend on each section of your essay. Do your best to leave at least 2 or 3 minutes at the end to make revisions. If you have 45 minutes to write, take about 5 minutes to make an outline. If you have an introduction, 3 main points that cite 6 documents, and a conclusion, plan on spending 7 minutes or less on each of these 5 sections. That will leave you 5 minutes to proofread or to serve as a buffer in case you need more time. Check the time periodically as you write to ensure you’re staying on target.

Include your thesis and 1 to 2 sentences of context in your introduction. If you’re taking an AP history exam, you’ll lose 1 point (out of 7) if you don’t relate the prompt to its broader historical context. Setting context is a natural way to start your essay, so consider using the first 1 to 2 sentences of your introduction to discuss context. To set the context, you might write, “The Progressive Era, which spanned roughly from 1890 to 1920, was a time of political, economic, and cultural reform in the United States. A central movement of the era, the Women’s Rights Movement gained momentum as perceptions of the role of women dramatically shifted.” If you’d prefer to get straight to the point, feel free to start your introduction with your thesis, then set the context. A timed DBQ essay test doesn’t leave you much time to write a long introduction, so get straight to analyzing the documents rather than spell out a long, detailed intro.

Write your body paragraphs. Your body paragraphs should be placed in a logical order, and each should address a component of your argument. For instance, you might discuss the attitudes toward women’s suffrage in the decades leading to World War I, then explain how women joined the workforce and supported the war effort. Finally, assess how these new roles gave further credibility to advocates of women’s rights and led to broader popular support. Each body section should have a topic sentence to let the reader know you’re transitioning to a new piece of evidence. For example, start the first section with, “The 1890s saw shifts in perception that set the stage for the major advances in women’s suffrage during and following World War I.” Be sure to cite your documents to support each part of your argument. Include direct quotes sparingly, if at all, and prioritize analysis of a source over merely quoting it. Whenever you mention a document or information within a document, add parentheses and the number of the document at the end of the sentence, like this: “Women who were not suffragettes but still supported the movement wrote letters discussing their desire to help (Document 2).”

Make sure to show how each body paragraph connects to your thesis. You won’t receive points if you just mention sources or add quotes arbitrarily. You must make logical connections between the documents, the inferences you’ve made, and your thesis. Additionally, demonstrate that you’ve developed a critical understanding of your sources by focusing on what they mean instead of what they say. For example, a private diary entry from 1916 dismissing suffrage as morally corrupt isn’t necessarily a reflection of broader public opinion. There's more to consider than just its content, or what it says. Suppose a more reliable document, such as a major newspaper article on the 1916 Democratic and Republican national conventions, details the growing political and public support for women’s suffrage. You’d use this source to show that the diary entry conveys an attitude that was becoming less popular.

Weave together your argument in your conclusion. While you should sum up your argument, your conclusion shouldn’t merely restate or rephrase your thesis and introduction. Remind the reader of how you’ve proved your claims, and take the opportunity to connect your argument to a broader historical context. In your essay on World War I and women’s suffrage, you could summarize your argument, then mention that the war similarly impacted women’s voting rights on an international scale.

Revising Your Draft

Proofread your essay for spelling and grammatical mistakes. Try to leave about 5 minutes after writing your essay to proofread and make final edits. Look for misspelled words, grammatical errors, missing words, and spots where your handwriting is sloppy. If you’re taking an AP history exam or other timed test, minor errors are acceptable as long as they don't affect your argument. Spelling mistakes, for instance, won’t result in a loss of points if the scorer can still understand the word, such as “sufrage” instead of “suffrage.”

Make sure you’ve included all required elements. If there’s time, and if it’s feasible, try to add any elements you’re missing. Rewriting a section or making major organizational changes with 3 minutes left isn’t practical, so check off your criteria as you outline and write. If you’re taking an AP exam, you’ll need to include these elements to receive 7 out of 7 points: A clear thesis statement. Set the prompt’s broader historical context. Support your argument using 6 of the 7 included documents. Identify and explain 1 piece of historical evidence other than the included documents. Describe 3 of the documents’ points of view, purposes, audiences, or context. Demonstrate a complex understanding of the topic, such as by discussing causation, change, continuity, or connections to other historical periods.

Check that your names, dates, and other facts are accurate. Ensure you’ve accurately cited names, dates, places, and points of view as they appear in the provided documents. For each reference, double check that you’ve cited the right document and accurately presented its content. As with spelling and grammar, minor errors are acceptable as long as the scorer knows what you mean. Little spelling mistakes are fine, but you’ll lose points if you write that a source supports suffrage when it doesn’t.

Comments

0 comment