views

From the outrage of Jallianwalla Bagh massacre, Mahatma Gandhi had forged a nationwide uprising against the British — the Non-Cooperation Movement. The movement had gained tremendous pan-India momentum before Gandhi called it off, after a mob set fire to a police station in Chauri Chaura in which 22 policemen died. Gandhi was sentenced to six years in jail, but was released in February 1924 due to his failing health. Upon his release, Gandhi began a new movement — the Charkha — a protest against British might rooted in self-reliance.

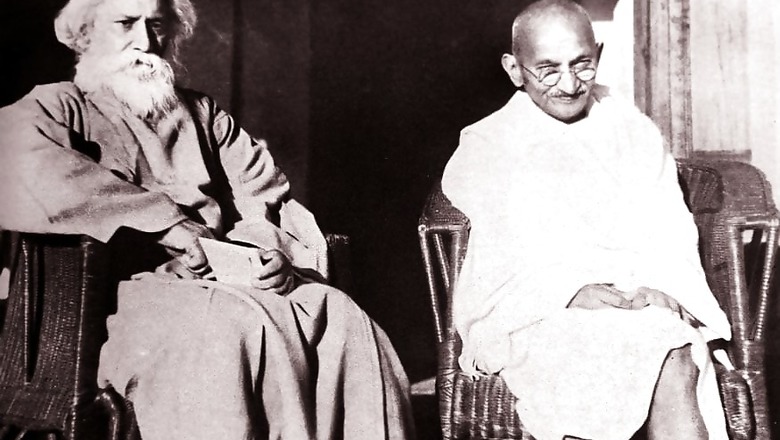

Gandhi’s stature was sky-high, as were nationalist passions, when Rabindranath Tagore, the most celebrated poet of his time, wrote a scathing piece in Modern Review, a Calcutta-based magazine of great repute, titled The Cult of the Charkha.

The article criticised not just the Non-Cooperation Movement, the Charkha, but the ideas of patriotism and nationalism as well, which Gandhi stood up for.

“As is livelihood for the individual, so is politics for a particular people — a field for the exercise of their business instincts of patriotism. All this time, just as business has implied antagonism so has politics been concerned with the self-interest of a pugnacious nationalism," Tagore wrote in the September 1925 edition of Modern Review.

Tagore’s criticism and Gandhi’s reception of the article, along with several other exchanges, show not just the intellectual depth of the two giant thinkers of modern India, but also the motions that ideas like patriotism, nationalism and Swaraj went through; the respectful but irreverent conversations in which they were born, before becoming the founding principles of Independent India.

Speaking of giant thinkers of modern India, Jawaharlal Nehru remarked that “No two persons could probably differ so much as Gandhi and Tagore. The surprising thing is that both of these men with so much in common and drawing inspiration from the same wells of wisdom and thought and culture, should differ from each other so greatly!... I think of the richness of India’s age-long cultural genius, which can throw up in the same generation two such master-types, typical of her in every way, yet representing different aspects of her many-sided personality."

French writer and Nobel laureate Romain Rolland called this exchange of ideas “the noble debate" that, as it were, “embraces the whole earth, and the whole humanity joins in this august dispute".

THE EXCHANGE OF IDEAS

Tagore on Gandhi’s call for Non-Cooperation

‘What is swaraj! It is maya, it is like a mist, that will vanish leaving no stain on the radiance of the Eternal. However we may delude ourselves with the phrases learnt from the West, Swaraj is not our objective. Our fight is a spiritual fight, it is for Man. We are to emancipate Man from the meshes that he himself has woven round him — these organisations of National Egoism.

The butterfly will have to be persuaded that the freedom of the sky is of higher value than the shelter of the cocoon. If we can defy the strong, the armed, the wealthy, revealing to the world power of the immortal spirit, the whole castle of the Giant Flesh will vanish in the void. And then Man will find his Swaraj. We, the famished, ragged ragamuffins of the East, are to win freedom for all Humanity.

We have no word for Nation in our language. When we borrow this word from other people, it never fits us. For we are to make our league with Narayan, and our victory will not give us anything but victory itself; victory for God’s world. I have seen the West; I covet not the unholy feast, in which she revels every moment, growing more and more bloated and red and dangerously delirious. Not for us, is this mad orgy of midnight, with lighted torches, but awakenment in the serene light of morning.’

— Published in Modern Review in May 1921

***

Gandhi’s response to Tagore’s criticism of Non-Cooperation

‘I, therefore, think that the Poet has been unnecessarily alarmed at the negative aspect of Non-cooperation. We had lost the power of saying ‘no’. It had become disloyal, almost sacrilegious to say ‘no’ to the Government. This deliberate refusal to cooperate is like the necessary weeding process that a cultivator has to resort before he sows. Weeding is as necessary to agriculture as sowing. Indeed, even whilst the crops are growing, the weeding fork, as every husbandman knows, is an instrument almost of daily use.

The nation’s Non-cooperation is an invitation to the Government to cooperate with it on its own terms as is every nation’s right and every good government’s duty. Non-cooperation is the nation’s notice that it is no longer satisfied to be in tutelage.

The nation had taken to the harmless (for it), natural and religious doctrine of Non-cooperation in the place of the unnatural and irreligious doctrine of violence. And if India is ever to attain the Swaraj of the Poet’s dream, she will do so only by Non-violent Non-cooperation. Let him deliver his message of peace to the world, and feel confident that India, through her Non -cooperation, if she remains true to her pledge, will have exemplified his message.

Non-cooperation is intended to give the very meaning to patriotism that the Poet is yearning after.

An India prostrate at the feet of Europe can give no hope to humanity. An India awakened and free has a message of peace and goodwill to a groaning world. Non-cooperation is designed to supply her with a platform from which she will preach the message.

— Published as an article in Young India on June 1, 1921, titled ‘The Poet’s Anxiety’

***

Right after World War I, Tagore urges nationalists to rise from ‘self interest’, reconsider non-cooperation, and instead work for ‘welfare of the world’

‘The time, moreover, has arrived when we must think of one thing more, and that is this. The awakening of India is a part of the awakening of the world. The door of the New Age has been flung open at the trumpet blast of a great war. We have read in the Mahabharata how the day of self-revelation had to be preceded by a year of retirement. The same has happened in the world today.

Nations had attained nearness to each other without being aware of it, that is to say, the outside fact was there, but it had not penetrated into the mind. At the shock of the war, the truth of it stood revealed to mankind.

The foundation of modern, that is Western, civilisation was shaken; and it has become evident that the convulsion is neither local nor temporary but has traversed the whole earth and will last until the shocks between man and man, which have extended from continent to continent, can be brought to rest, and a harmony be established.

From now onward, any nation which takes an isolated view of its own country will run counter to the spirit of the New Age, and know no peace.

From now onward, the anxiety that each country has for its own safety must embrace the welfare of the world. For some time the working of the new spirit has occasionally shown itself even in the Government of India, which has had to make attempts to deal with its own problems in the light of the world problem. The war has torn away a veil from before our minds.

What is harmful to the world, is harmful to each one of us. This was a maxim which we used to read in books. Now mankind has seen it at work and has understood that wherever there is injustice, even if the external right of possession is there, the true right is wanting. So that it is worthwhile even to sacrifice some outward right in order to gain the reality. This immense change, which is coming over the spirit of man raising it from the petty to the great is already at work even in Indian politics. There will doubtless be imperfections and obstacles without number. Self-interest is sure to attack enlightened interest at every step.

Nevertheless it would be wrong to come to the decision that the working of self-interest alone is honest, and the larger-hearted striving is hypocritical.

In this morning of the world's awakening, if in only our own national striving there is no response to its universal aspiration, that will betoken the poverty of our spirit.

— Published in piece titled ‘The Call of Truth’ in Bengali in Pravasee first and later in Modern Review

***

Gandhi defends Charkha, Non-cooperation and Swaraj. On internationalism, he says, ‘a drowning man cannot save others’

‘Hunger is the argument that is driving India to the spinning wheel. The call of the spinning wheel is the noblest of all. Because it is the call of love. And love is Swaraj. The spinning wheel will ‘curb the mind’ when the time is spent on necessary physical labour can be said to do so.

Our Non-cooperation is with the system the English have established, with the material civilisation and its attendant greed and exploitation of the weak. Our Non-cooperation is a retirement within ourselves. Our Non-cooperation is a refusal to cooperate with the English administrators on their own terms. We say to them, ‘Come and co-operate with us on our terms, and it will be well for us, for you and the world.’ We must refuse to be lifted off our feet. A drowning man cannot save others. In order to be fit to save others, we must try to save ourselves.

Indian nationalism is not exclusive, nor aggressive, nor destructive. It is health giving, religious and therefore humanitarian.

India must learn to live before she can aspire to die for humanity. The mice which helplessly find themselves between the cat’s teeth acquire no merit from their enforced sacrifice.’

— Published in piece titled ‘The Great Sentinel’ in October 1921, in Young India, as a response to ‘The Call of Truth’

***

Tagore excoriates Gandhi’s ideas and calls the prevalent nationalist politics of the time a ‘pugnacious nationalism’

Swaraj cannot be based on any external conformity, but only on the internal union of hearts. If a great union is to be achieved, its field must be great likewise. But if out of the whole field of economic endeavour only one fractional portion be selected for special concentration thereon, then we may get home-spun thread, and even genuine khaddar, but we shall not have united, in the pursuit of one great complete purpose, the lives of our countrymen.

As is livelihood for the individual, so is politics for a particular people — a field for the exercise of their business instincts of patriotism. All this time, just as business has implied antagonism so has politics been concerned with the self-interest of a pugnacious nationalism. The forging of arms and of false documents has been its main activity. The burden of competitive armaments has been increasing apace, with no end to it in sight, no peace for the world in prospect.

— Published in piece called ‘The Cult of the Charkha’ in September 1925 in Modern Review

***

Gandhi bristles at the supposed ignorance of the idea that Tagore has mockingly called ‘The Cult of the Charkha’

The Poet lives in a magnificent world of his own creation—his world of ideas. I am a slave of somebody else's creation—the spinning wheel. The Poet makes his gopis dance to the tune of his flute. I wander after my beloved Sita, the charkha and seek to deliver her from the ten-headed monster from Japan, Manchester, Paris etc. The Poet is an inventor — he creates, destroys and recreates. I am an explorer and having discovered a thing I must cling t0 it.

The Poet does not, he is not expected, he has no need, to read Young India. All he knows about the movement is what he has picked up from table talk. He has therefore denounced what he has imagined to be the excesses of the charkha cult.

He thinks for instance that I want everybody to spin the whole of his or her time to the exclusion of all other activity; that is to say that I want the Poet to forsake his muse, the farmer his plough, the lawyer his brief and the doctor his lancet. So far is this from truth that I have asked no one to abandon his calling, but on the contrary to adorn it by giving every day only thirty minutes to spinning as sacrifice for the whole nation. I have indeed asked the famishing to spin for a living and the half-starved farmer to spin during his leisure hours to supplement his slender resources. If the Poet spun half an hour daily his poetry would gain in richness. For it would then represent the poor man's wants and woes in a more forcible manner than now.

But the exchanges between Gandhi and Tagore weren’t only sparks and fire produced by crashing of two flint stones. ‘Mahatmaji’ and ‘Gurudev’ as the two referred to each other, privately loved and remembered each other in despair, while flaying each other’s ideas in public.

Describing his relationship with Tagore, Gandhi wrote this piece in Young India on February 25, 1926 -

“I have not differed from Dr. Tagore in many matters. There are certainly differences of opinion between us in some matters. It would be strange if there were none.... Indeed the friendship between us is all the richer and truer for the intellectual differences between us."

Here are some letters and cables that the two wrote directly to each other.

Gandhi to Tagore on the resumption of Civil Disobedience Laburnum Road, Bombay, 3 January 1932

‘Dear Gurudev,

I am just stretching my tired limbs on the mattress and as I try to steal a wink of sleep, I think of you. I want you to give your best to the sacrificial fire that is being lighted.

With love

MK Gandhi’

— Published in a piece titled ‘The Poet and the Charkha’, in Young India, in November 1925

***

Tagore’s letter, during his illness, to Gandhi sometime in September — October 1940

‘6 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane, Calcutta

Mahatma Gandhi, Wardha

Your constant good wishes have brought me back from die land of darkness into the land of light and life and my first offering of thanks goes out to you.

Rabindranath’

***

Gandhi’s birthday wishes to Tagore sent through cable on April 13, 1941

‘Gurudev, Shantiniketan

Four score not enough may you finish five.

Love Gandhi’

***

Tagore’s cable reply to Gandhi’s wishes

‘Thanks message but four score is impertinence, five score intolerable.

Rabindranath’

***

Gandhi’s letter to Tagore written with left hand

‘Dear Gurudev,

Your precious letter is before me. You have anticipated me. I wanted to write as soon as Sir Nilratan sent me his last reassuring wire. But my right hand needs rest. I did not want to dictate. The left hand works slow. This is merely to show you what love some of us bear towards you. I verily believe that the silent prayers from the hearts of your admirers have been heard and you are still with us. You are not a mere singer of the world. Your living word is a guide and an inspiration to thousands. May you be spared for many a long year yet to come.

With deep love,

Yours sincerely, M.K. Gandhi’

— From his ashram in Wardha on September 23, 1937

(Introduction by Suhas Munshi)

Comments

0 comment