views

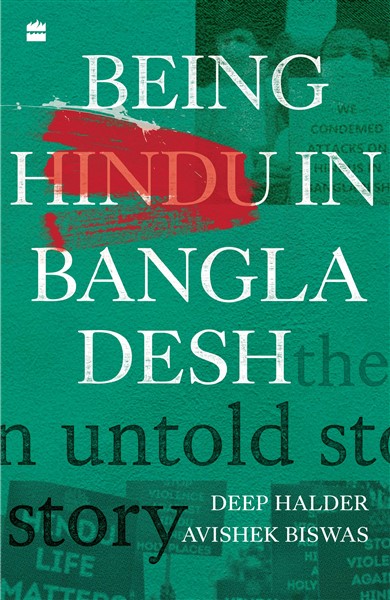

What’s being a Hindu in Bangladesh — or in Pakistan? A new book on this theme has just come out, written by senior journalist Deep Halder and academic Avishek Biswas. What makes Being Hindu in Bangladesh (HarperCollins, Rs 399) a compelling read is the passion with which it is written, thanks primarily to the “refugee blood” in the two authors, and also the perfect blend of academic rigour with journalistic flair.

A Bangladeshi Hindu may today feel dejected at two levels. One, he belongs to a religion which has just one country to look up to — for help, survival and more. (While Muslims are in majority in 49 nations, the number of Christians easily breaches the three-figure mark.) And that one country and its inhabitants are largely indifferent to their plight. Two, a Bangladeshi Hindu is seen to be carrying the baggage of being the civilisational part of Bharat, which no longer cares for him. So, if there is a Hindu-Muslim discord in Bharat, the Hindus of Bangladesh pay back with their lives and properties.

Deep Halder and Avishek Biswas face these two questions as they meet a victim of the 2021 anti-Hindu violence at Noakhali in Bangladesh. The victim, a woman called Mukta Saha, asked them where they were when Hindus were being attacked. “‘We?’ we asked incredulously. ‘When neighbours become murderers, shouldn’t strangers come to save us?’ she asked us.”

Mukta Saha had lost a lot in the 2021 anti-Hindu violence. “We died last year. What you see are corpses,” she added.

There’s one more reason that dismays a Hindu in Bangladesh, especially if he is a history buff — the utter failure of its leaders not once but twice. The job of a leader is to lead his/her people out of a precarious situation. But at the time of Independence, the national leaders led by Mahatma Gandhi extensively campaigned to convince Hindus of West and East Pakistan not to migrate to India. They were told about a large number of Muslims staying back in India despite Partition and their presence there meant a guarantee of Hindu safety in West and East Pakistan. Ironically, while Muslims in India prospered, the same cannot be said about minorities in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The Hindus of East Pakistan were also let down by their own local, regional leaders, the tallest of them being Jogendra Nath Mandal, who was so influential at the time of Independence that he got Dr BR Ambedkar elected to the Constituent Assembly from Bengal when the latter failed to get into the august body from Bombay, thanks to the Congress’ intense opposition. But while Ambedkar saw the Dalit-Muslim alliance as a tactical one, Mandal was naïve enough to take it at face value. Mandal so ardently believed in the Dalit-Muslim coalition that he refused to migrate to India and became the first law minister in the Jinnah Cabinet. And this one mistake cost his lower-caste Hindu followers, especially Namasudras, dearly.

The first wave of refugees from East Pakistan comprised the traditional upper-caste elite. Till the time these upper castes were there in East Pakistan, the Muslim League found Mandal and his lower-caste followers a useful ally. But once these upper-caste men and women left for India, the buffer was gone. The rationale for the Muslim-Dalit coalition collapsed under the weight of reality in East Pakistan. Thus began a series of Islamist violence on these people. By October 1950, things came to such a pass that Mandal had to resign from the Pakistan Cabinet. He migrated to India soon after. For his followers, the return wasn’t that easy.

The people of East Pakistan also faced the double whammy of Partition. While the people of West Pakistan encountered a jhatka-style operation as the entire population was uprooted and shifted at one go, those in East Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) were doomed to suffer a halal-type persecution: They were roasted on a low-flame Islamist burner with intermittent shifting to jhatka-style killings whenever tempers soared — the last time it happened in Bangladesh when a copy of the Quran was found at the feet of Lord Hanuman at a Durga Puja pandal in 2021; it later turned out to be the handiwork of a Muslim man, but the damage was done by then.

The book quotes The Daily Star, the largest-circulating daily English-language newspaper in Bangladesh, as saying that “117 Hindu temples or puja pandals and 301 shops/homes were also damaged” after the Noakhali pandal incident.

“If a fake news item that a Hindu has kept the Quran at the feet of Hanuman can lead to such mayhem, what hope do we have,” the book quotes Rosopriya Das, head priest of ISKCON temple in Noakhali who too was a victim of Islamist fury in 2021. “Yes, only two people might have died in Noakhali in last year’s violence. But look around and you will find boys and men without an arm or a leg walking around. They would remind you of what was.”

This was not the first time that fake news started an orgy of violence against Hindus in East Pakistan/Bangladesh. In 1946 too, which had seen unprecedented violence and killings, it all started with fake news. The supporters of a local Pir, Ghulam Sarwar Hussaini, spread misinformation about a local zamindar, Rajendralal Chowdhury, saying he was organising “some dark ritual with Muslim blood”. “On 11 October, a Muslim mob attacked Chowdhury’s house. He, with his family members and neighbours, put up a courageous resistance. But not for long.” After killing them, they turned towards the ordinary Hindus.

Language and culture often work as an antidote to religious fundamentalism. The strength of the two was seen in 1971 when Bangladesh rebelled out of Pakistan despite coming into existence in the name of a religion. However, Islamism is a tenacious force. It weathers away the strength and vitality of culture and language that unite people beyond religions. In Bangladesh, the battle between the two is on. The authors, thus, write, “…if one hypothesis is found to be true, the exact opposite is almost always true as well. A strong argument can be made that Hindus are under siege in Bangladesh. But an equally strong counter-argument can be put out that Hinduism is alive and thriving in the country.”

Sadly, with each passing day, the forces of Islamism are gaining ground over liberal forces. While Section I of the book focuses on ‘Fissure’ within Bangladeshi society, with chapters “Noakhali: 1946, 2021”, “Horror in the Countryside” and “The DNA of Hate”, Section II talks about ‘Fusion’. The third section, however, with chapters such as “1971 Has Not Ended” and “A Father’s Dream, A Daughter’s Challenge”, comes up with a not-so optimistic ‘Forecast’.

So, here’s the forecast: “Thirty years from now, no Hindus will be left in Bangladesh should the current rate of exodus continue. ‘The rate of exodus over the past 49 years points in that direction,’ predicts Dr Abul Barkat, a Dhaka University professor. On an average, as of 2016, 632 people from the minority community leave the country each day,” write Halder and Biswas.

But why such a gloomy prospect? And who do you blame for it? Of course, it has to do with the fundamental nature of an Islamic society where liberals function well in normal circumstances. But during perceived emergency, war-like situations, the liberal class makes a vanishing act and becomes a part of the larger ummah. In fact, as the book suggests, on finer points there is little difference in the policy of the ‘liberal’ Awami League and the ‘fundamentalist’ Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BMP). For, as one BNP leader reminded the authors of this book, “I can give you many examples to show that most of the anti-Hindu policies have taken place during the Awami League… The Enemy Property Act was renamed Vested Property Act in 2013 but the intention remained the same… Across Bangladesh, Awami League leaders have misused this act and seized Hindu property.”

Author Aatish Taseer explores this phenomenon quite eloquently in his book, Stranger to History, wherein he writes how his father was not a practising Muslim and liked to call himself a ‘cultural Muslim’ — and yet, he saw himself a defender of the faith who ‘doubted the Holocaust, hated America and Israel, thought Hindus were weak and cowardly’. Aatish Taseer’s father was the well-known Pakistani liberal and Governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer, who was killed by his bodyguard in 2011 for opposing his country’s blasphemy law.

The blame also lies with Bharat, which invariably looks the other way when Hindus are persecuted and killed in its neighbourhood, especially in Bangladesh. Ironically, when the Narendra Modi government tried to correct this anomaly and came out with the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, it was a Hindu-versus-Muslim issue. The fate of the legislation hangs in the balance today. So is the future of Hindus in India’s immediate neighbourhood.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment