views

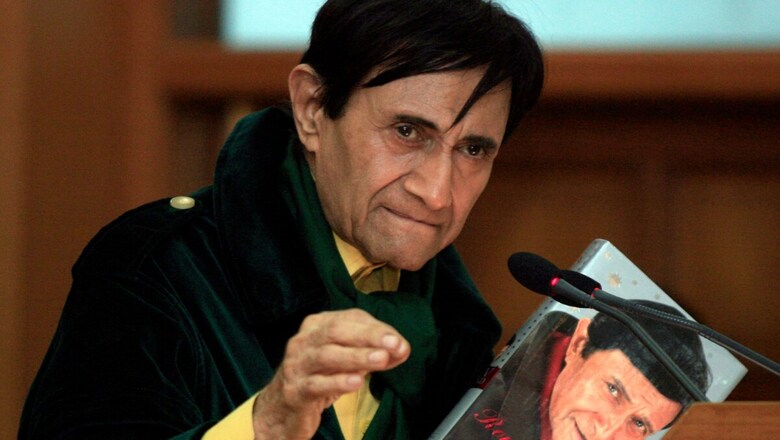

Dev Anand, whose birth centenary is being celebrated today, is usually presented as an evergreen, debonair, flamboyant, romantic film star—and little more than that. However, he was much more than a hero who entertained generations and charmed women. The movies he acted in, produced, and directed created a universe in which modern virtues and values like equality and individualism were cherished and esteemed.

His modernity, however, was never loud or pompous, as was the case of many others, including the champions of art house cinema; modernity was embedded, almost concealed, in the narratives his movies depicted on celluloid. Art, as they say, lies in concealing art.

Few have been able or willing to recognize the Dev Anand phenomenon; the stylish actor and filmmaker portrayed the variegated nuances of the urban male in a young, modernizing nation. He broke new grounds. How many would have dared to delineate a quasi-incestuous theme (Bumbai ka Babu) or an adulterous, inter-religious affair (Guide) over half-a-century ago?

In 1953, he starred in a movie called Patita (A Fallen Woman), in which he marries the protagonist (Usha Kiran) who was raped by the villain of the movie. It also resulted in a child. Yet, he married her because he loved her.

Compare this with Raj Kapoor’s Sangam, which was made more than a decade later. One of the most reactionary Hindi movies ever made, Sangam shows how two friends are keen to sacrifice their love for each other, in effect transforming the woman they love into an object that is fungible. Kapoor, who plays the lead role, is married to Radha (Vyjayanthimala). While not doubting her fidelity, he is incensed that another man might have touched her before marriage. The movie was so regressive that even the character of Radha rebelled against the director.

In Guide (1965), a married woman wants to follow her passion—dance. Instead of convincing her to follow her customary wifely duties, Dev Anand inspires her to listen to her heart and showcase her talent to the world, resulting in elopement.

And, of course, he was a perfect gentleman—both on- and off-screen—but he was also someone who was never without refinement. To put it in another way, he was never a chhichhora, tapori, or punk in any movie. The characters he depicted onscreen were often flawed—a crook, a pickpocket, a gambler, a dacoit, et al—but never a punk. Dev Anand talking like Sanjay Dutt’s Munna Bhai is inconceivable. Dev sahib could be a criminal, but not a punk. And when he was not a gentleman, he would aspire to become one (Baazi).

In the 1950s and the 1960s, Dev Anand defined heroism; he was urban, urbane, stylish, handsome, and gentlemanly. He was the kind of man girls dream about and women long to be seen with. Of course, his persona also had a wicked aspect, as I just mentioned. Dev Anand depicted several negative characters but he excelled in the role of a gambler. I have not come across any film star, in Hindi cinema or in Hollywood, who has gambled onscreen with such aplomb. The tilted head, a cigarette hanging delectably between his lips, the saucy dialogues which only Dev Anand could speak.

Another aspect stands out. The moral fiber never snapped. Unlike Shah Rukh Khan in Baazigar, Dev Anand never murdered innocent people. Nor did he justify his crimes, as Amitabh Bachchan did in Deewar.

Of course, the circumstances (or haalaat, the oft-quoted term in Hindi cinema) goaded him to become an outlaw; an existence beyond the domain of law and decency never became an alternative, sustainable existence. The hero always felt the need for redemption; and he would almost invariably redeem himself, at great cost and after suffering a great deal of pain. In Pocketmaar, Dev Anand eschews his life as a pickpocket; he has to suffer a lot in the process. Similarly, in Gambler, he willingly gives up a life of ease, cunning, and transgression for an existence that is full of misery and despair (e.g., ditto with House No. 44 and Kala Bazaar).

Yet, despite all the adulation and awards (including the much-coveted Dadasaheb Phalke Award) that he received, he did not have a cult following. Not a single dialogue from any of his movies figures in the most popular 10 dialogues from Hindi films; not a single intellectual, with the exception of Nasiruddin Shah, would admit their admiration for Dev Anand (Typically, intellectuals would talk about avant-garde filmmakers and ‘new wave’ actors).

This is primarily because Dev Anand never peddled syrupy socialism like Raj Kapoor did, promoted ‘progressive’ causes like Bimal Roy did, or produced nihilistic, ribald works like Anurag Kashyap does. Besides, Dev Anand also committed the cardinal sin of cultivating the image of a happy-go-lucky, Westernized chap.

In a society that celebrates sacrifice and self-abnegation, where cinema is regarded as crass entertainment unless it conveys some ‘message,’ it is to the credit of Dev Anand that his blithe persona is still held in high esteem and some of his movies are considered as great works of art. His persona continues to have the radiance of youth one hundred years after he was born. And that will stay the same.

The author is a freelance journalist. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment