views

Pakistan President Asif Zardari is visiting Gwadar at a time when the fifth insurgency since 1947 in Balochistan is now in its third decade. In 2009 in his previous term as President, Zardari had tried to bribe the Baloch with a package of economic and political sops called ‘Aaghaz-e-Huqooq-e-Balochistan’. While Zardari’s that attempt to assuage the Baloch sentiment failed miserably, he is once again trying to reach out to the Baloch, but as usual with empty words and insincere assurances.

During his visit he has called for political dialogue to bring prosperity, development and peace to the restive province. At the same time, he has called for enhancing the capacity of the law enforcement agencies. The incongruity of his message is clear to anyone who studies Balochistan: it is the lawlessness of the so-called ‘law enforcement’ and security agencies — the extortion, kidnapping, smuggling, narcotics and human trafficking networks they run — which makes them the greatest obstacle to peace in the province. What is more, the Punjab-dominated Pakistani state wants a dialogue not with genuine representatives of the Baloch but with those who will tow their line and remain subservient to the Punjabi establishment.

The result is that Balochistan has continued to burn ever since it was forcibly occupied by Pakistan in 1948. Since then, Pakistan has managed to keep its stranglehold over Balochistan, but only through brute force and censorship of the type that would embarrass even the Chinese.

When the first stirring of the latest and longest episode of Baloch anger against Pakistan’s neo-colonial exploitative and extractive rule started around 2001, no one expected it to last more than a few years. But the murder in 2006 of the venerable Bugti chieftain, Nawab Akbar Bugti, gave a major fillip to the Baloch movement. Since then the movement has ebbed and flowed but has continued to roll forward.

Over the last three years, especially since the Afghan Taliban broke the “shackles of slavery” of not only the Americans but also the Pakistanis, the Baloch freedom struggle has shifted gears and gained more pace. Of course, if anyone was to go through Pakistan’s mainstream media, it would seem the Baloch movement has run out of steam. This is primarily because of a clampdown on media by the military to stop the flow of bad news. But just because nothing is coming in the news doesn’t mean nothing is happening on the ground. The fact is that the Baloch movement is acquiring dangerous dimensions. It has probably still not reached the tipping point where it threatens the territorial borders or constitutional structure of Pakistan, but it is slowly and surely getting there, aided in large part by the growing disorder and disaffection that has engulfed the state of Pakistan.

The unrest in Balochistan is finding expression along two parallel tracks. Both of these are organic and entirely indigenous. No one in the rest of the world appears to be interested in even lending an ear to the grievances of the Baloch, let alone supporting them monetarily or materially. There is of course the militant track adopted by young Baloch cutting across class and tribal lines to challenge the might of the Pakistan Army. In recent years, there has been an increase in both the frequency as well as the ferocity in their attacks against the Pakistani state and its henchmen in uniform. The second track is that of peaceful protest, public mobilisation and resistance through a kind of civil disobedience. The protest track has galvanised the people like never before, something that was witnessed during the Haq Do Tehrik in Gwadar when thousands of people came out on the streets to press for their basic demand of right to life and livelihood.

The Haq Do Tehrik went on for months in the face of the usual shenanigans of the Pakistan Army-run state machinery that tried every trick in the book — bribes, intimidation, brutal crackdowns — to break the morale of the people. In the end, the state had to agree to the demands. But as is the wont of colonial occupiers, they never delivered on their side of the bargain. It is these kinds of betrayals of peaceful protests that then feed into the militants’ arguments that only armed resistance will force the Pakistani state to end its oppressive and repressive rule.

The same happened with the Long March led by the feisty young woman activist Dr Mahrang Baloch to Islamabad. In any genuinely democratic country, the authorities would not only have allowed the right to protest in Islamabad, but also dialogued with the protestors. But even the pretence of democracy has been given up by the hybrid regime that rules Pakistan — a civilian regime led by the puppet Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif whose strings are controlled by the military.

Although Dr Mahrang Baloch wasn’t able to make any breakthrough with her demands on ending enforced disappearances and extra-judicial killings, even massacres, by the Pakistani security forces, she became an iconic figure in Balochistan. The mammoth crowds that turned out to receive her when she returned left no doubt that a new star, nay a new leader, had been discovered. Activists like Dr Mahrang Baloch is in itself a remarkable development in Balochistan where women activists are assuming leadership roles in what is a very conservative and orthodox society. Even more astonishing is the fact that women are not just leading political protests, they are also involved in militancy.

The phenomenon of highly educated Baloch women activists becoming suicide bombers is something no one ever anticipated. Perhaps it is sheer desperation and despondency, the end of all hope, that has forced these women to take such a drastic step. For more than a decade, young and old Baloch women have been demonstrating and demanding to know the whereabouts of their husbands, sons, fathers, brothers who have been forcibly kidnapped by Pakistani security agencies. Most have probably been butchered by the Pakistan Army. There have been dozens of incidents of mutilated bodies of activists who were subjected to enforced disappearances being thrown on the roadside. There have even been cases of a few mass graves that have been uncovered. But there has been no closure for the Baloch, something that has continued to fuel militancy.

Even today, young Baloch students and activists who are studying in Punjab and other provinces have ‘disappeared’. Every other day there are reports of young people, householders, professionals who are victims of enforced disappearances by the security forces. The current Chief Minister of Balochistan, Sarfraz Bugti, a man who is notorious as not just a complete puppet of the military establishment but also has been accused of being involved with state-sanctioned and supported death squads that hunt down and kill Baloch activists. He is now assuring the people that he will start a new process of reconciliation. But no one is biting. No one trusts him.

There are, however, some signs of growing panic in the military establishment. Despite their brutality, and notwithstanding the thousands of people who have been forcibly disappeared or killed by the security forces, they haven’t been able to dampen the spirits and passions, nor lessen the disgust and contempt for Pakistan among the Baloch who keep struggling to break the shackles of slavery imposed on them by Pakistan. And this sentiment is growing, both politically as well as militarily.

The reports of tacit and perhaps tactical and temporary alliances between some Baloch militant groups and the Pakistani Taliban have multiplied the dangers for the Pakistani state. Despite both sides being poles apart ideologically — the Baloch are progressive and security in their outlook while the Taliban are regressive and Islamists in their worldview — the prospect of a combined Baloch and Pashtun resistance against a common enemy is quite dreadful for Pakistan, and for the region.

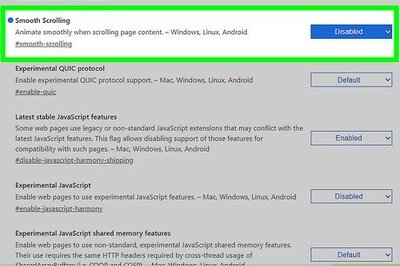

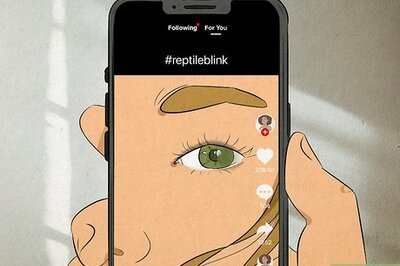

Even as the militancy picks up steam, the political mobilisation to challenge the Pakistani state progresses apace. The Pakistani mainstream media is of course ignoring the simmering situation in Balochistan. But just because the media is not reporting something, it doesn’t mean nothing is happening. In fact, this has been a long standing problem in Pakistan. Because of the muzzling of the media by the military, the people come to know of a disaster only when it is too late. Perhaps some of this can be addressed by social media. But even here there is an effort to impose censorship of the China variety.

Ironically, Pakistanis are all outraged and enthused in equal measure by the Israeli action against Hamas and the widespread anti-Semitic and pro-Palestine, even pro-Hamas, protests in US university campuses. But inside Pakistan, there hasn’t been a whimper of protest from these same students, human rights activists, media persons, civil society butterflies over the repression that has been unleashed against the Baloch and Pashtuns by the Punjabis. In fact in campuses in Punjab, mobs of Punjabi students, most of them aligned to the Jamaat Islami, and backed by the university authorities and the military establishment have been carrying out attacks on the Baloch and Pashtun students for so much as celebrating their own culture.

Instead of using protests and civil disobedience in Balochistan to take a political initiative and engage the representatives of the Baloch, the Pakistan Army has decided to crush it with brute force and foist their own Quislings like Sarfraz Bugti to suppress the voices of dissent. But that is only fuelling the anger against Pakistan and creating a situation that is fast reaching the point of too return. The only thing that has worked so far for Pakistan is the inability of the Baloch to unite under a common leadership — both political and military. This allows Pakistan to divide and rule by exploiting the petty egos of tribal chiefs, their mutual rivalries and feuds, and throwing some crumbs of power and privilege to win over otherwise discredited ‘nationalist’ politicians. Until the Baloch are able to unite under a common flag, Pakistan will continue its colonial approach and genocidal policy in Balochistan.

The writer is Senior Fellow, Observer Research Foundation. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment