views

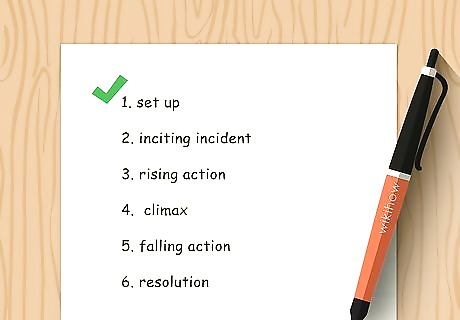

Outlining the Plot

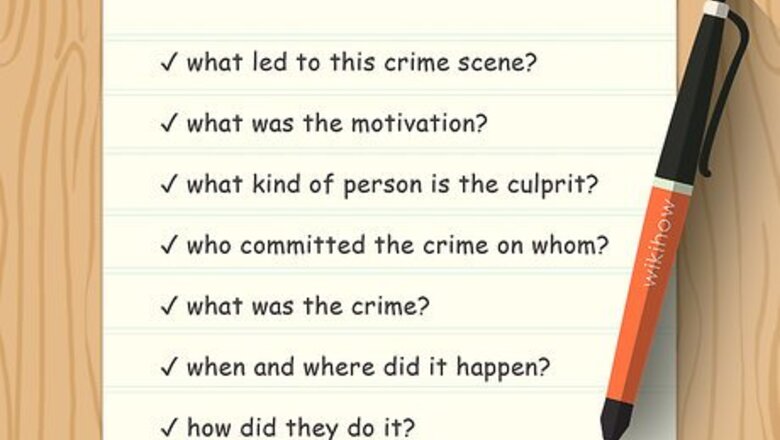

Try working backward. Most crime stories begin with the crime, and this can be a handy technique for the author as well. Briefly describe an exciting or mysterious crime scene: jewels disappearing from inside a locked safe, a fortune teller found dead in a canoe, or the prime minister's secretary caught carrying a bomb into 10 Downing Street. Ask yourself the following questions, and use the answers to sketch out a rough idea of the plot: What could have led to this crime scene? What motivation would cause someone to commit the crime, or to frame someone else? What kind of person would follow through on that motivation? Use Who? What? When? Where? Why? How? questions to get you started: Who committed the crime and who did they do it to? What was the crime? When did it happen (morning, evening, afternoon, dead of night)? Where did it happen? Why did they do it? How did they do it?

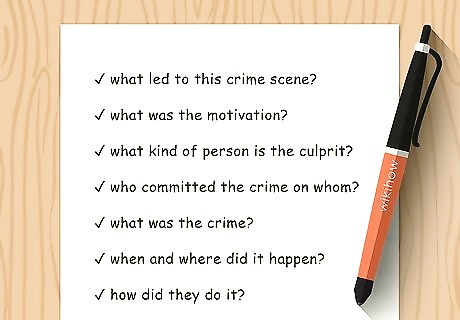

Choose a setting. Your setting should be described in sufficient detail that the reader has a clear mental image of the location, whether it's a lady's parlor or a battlefield. Your mystery short story may be set in one room, one house, one city, or around the world; regardless, make sure that you provide a detailed and vivid description of the setting for your mystery short story. Recognize that the size of the place will influence the development of your story. For example, in a large city or busy public place, you will have lots of opportunities to introduce witnesses. However, in a “locked-room mystery” (one where all the characters seem to be present in the same room throughout the occurrence of the crime), you will likely have no external witnesses, but may be able to draw upon your characters opinions and biases of each other. Focus on the elements of your setting that are essential to the story. For example, is weather essential? If it is, write about it in great detail. If it is not, only mention it briefly or leave it out altogether. A dark, gritty setting adds atmosphere and works well with stories centered on organized crime. Setting a crime in an idyllic, ordinary town adds its own kind of chill.

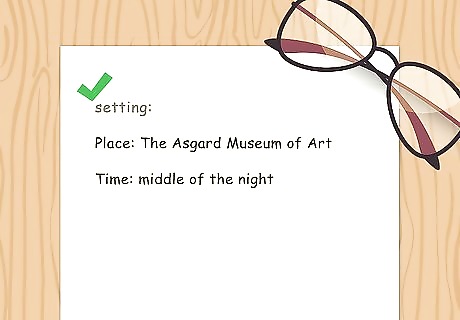

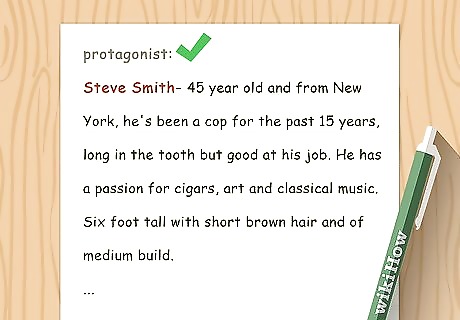

Decide on a protagonist. Create compelling characters. In a mystery, you'll want to make sure each character is both realistic and easily identifiable. Make sure their names are distinct, that each has uniquely identifying features, and that they have ways of acting or speaking that are unique. Some characters should be potential suspects for having committed the crime (and at least one should actually be guilty of the crime), some should be supporting characters that serve to make the storyline interesting (a love interest or meddling mother-in-law, perhaps), and one (or more) should be focused on solving the mystery. Well-written characters will have motives for acting in ways that further the plot.Okay, the gritty noir detective or genius investigator is an option, but come up with alternatives or twists. Make the crime matter personally to the protagonist, to raise the emotional stakes. This could be related to the protagonist's mysterious past, a close friend or family member in danger, or the fate of the town, country, or world.

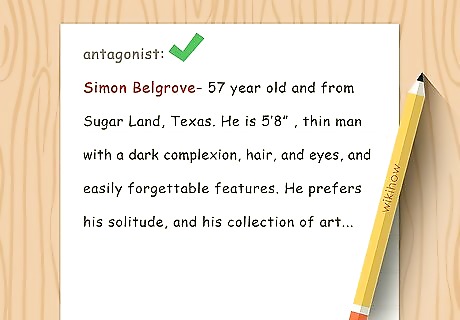

Consider your antagonist or villain. Who is the “bad guy” (or gal) in your mystery short story? To add some extra spice to your story, you may want to consider presenting a few potential villains with suspicious characteristics. This will leave your reader guessing as to who is the real antagonist in your story. Describe your villain well, but not too well. You don’t want your reader to guess right from the beginning of the story who is the culprit. Your reader may become suspicious if you spend a disproportionate amount of time describing one character. You may want to make your villain someone that has been slightly suspicious all along. On the other hand, you may want to make the revelation of the culprit or criminal a complete shock. “Framing” someone throughout the story is a surefire way to keep your readers hooked to your mystery short stories. Instead of a villain, consider including a sidekick. Maybe your sleuth has a friend or partner that will help her sort the clues and point out things that she misses. No one says the sleuth has to do it all alone! What if the sidekick and villain end up being one in the same? Think of the basics. Male or female? What is the detective's name? How old are they? What do they look like (hair color, eye color, and skin tone)? Where are they from? Where are they living when your story starts? How did they become part of the story? Are they victims? Are they the cause of the problems in your story?

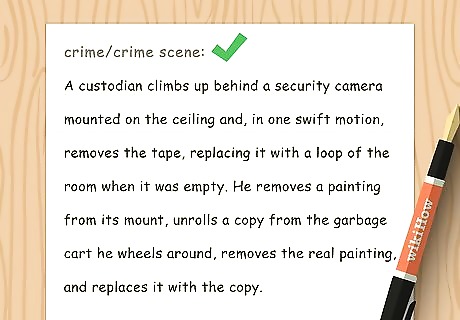

Think about the crime scene. This is an especially important part of your story, so take the time to really develop it fully. Try to describe every single detail so that the reader can picture the crime scene. What does it look like? Is it different by day than by night?. Present an opportunity for mystery. Create a situation in which a crime can reasonably occur and one that you will be able to reasonably recreate yourself. Did all the power go out in the city due to a thunderstorm? Was a door or a safe accidentally left unlocked? Paint a vivid picture of the situation surrounding the occurrence of the crime that will be the focus of your mystery. Don’t underestimate the power of the “backdrop” for the crime. An intricate understanding of the setting in which the crime takes place is an important tool that will help when it comes to developing your narrative. Here are some suggestions for crimes: Something has been stolen from the classroom, Something is missing from your bookbag, Something strange is found on the baseball field, Someone has stolen the class pet, Someone is sending you strange notes, Someone has broken into the Science materials closet, someone has written on the bathroom wall, someone has tracked red mud into the building.

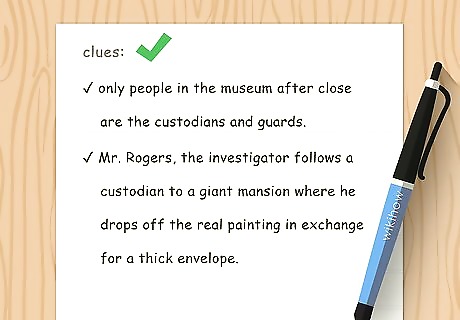

Consider clues and the detective work. What kind of clues will you have? How will they be linked to the possible suspects? How will they be processed? You should include evidence processing skills such as fingerprinting, toxicology, handwriting analysis, blood spatter patterns, etc. The detective work must be good. Develop how your detective or protagonist ultimately solves the case, keeping their personality and qualities in mind. Make sure it isn't cheesy or too obvious.

Collaborate as a writing group. Work together as a group to make your story and your crime scene interesting and be sure you will be able to re-create the crime scene.

Writing the Story

Establish the genre. The crime, or the discovery of the crime scene, almost always occurs in the first chapter, but this cliché can be effective. Right away, it establishes the tone of the story, whether that's occult, violent, emotional, suspenseful, or exciting. If your crime story is a whodunnit, the unusual nature of the crime or the hints dropped throughout the scene gets the gears turning in the reader's head. If you want to write about what happens before the crime, you can go back in time for the second chapter, adding a subheading such as "one week earlier."

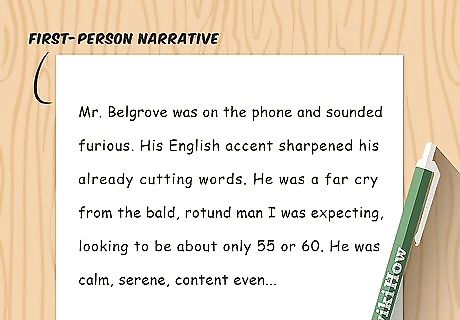

Choose a perspective. Most mystery authors choose a point of view that hides as much information about the mystery as possible, without confusing the reader. This can be the protagonist's first-person perspective, or a third person perspective that most sticks near the protagonist's actions. Think carefully before moving to another person's thoughts; it's possible to pull it off, but often adds unnecessary complexity.

Research when necessary. Most crime stories are written for a popular audience, not FBI agents or expert criminals. Your readers don't need perfect realism to enjoy a story, but the major plot elements should be fairly believable. You can find a ton of information online or at a library, but extremely specialized subjects may require asking questions from someone who works in the field, or in a specialized online forum.

Stay on track. If a scene doesn't relate to the crime or the investigation, ask yourself what it's doing there. Romance, side plots, and long, casual conversations have their place, but they should never steal the spotlight from the main plot and the main characters. This is especially true for short stories, which can't afford to waste any words.

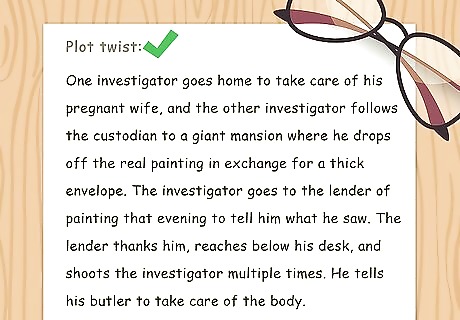

Use plot twists with caution. If you love a good surprise, go ahead and include the astonishing reveal — and stop there. A second plot twist in the same story makes the reader feel cheated, especially if it's almost impossible to guess in advance. Even the most unlikely plot twist should have a few hints sprinkled earlier in the book, so it doesn't come completely out of the blue. This is especially important for the biggest reveal — whodunnit? — and the wrong choice can ruin a novel for a lot of readers. The villain should either be a suspect or demonstrate enough suspicious behavior that a clever reader can guess the identity.

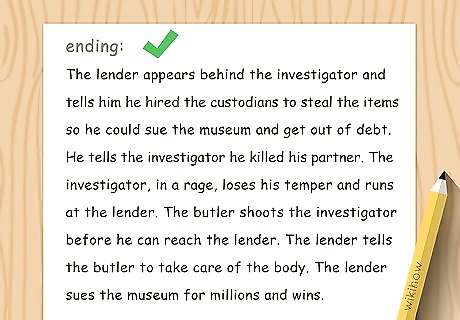

End on a dramatic note. Have you ever read the final, climactic scene of a book, then turned the page to discover a ten-page conversation with a side character? Whatever other goals you have for the story, the crime novel's main focus is the criminal investigation. When the villain meets a bad end, write your poignant final paragraph and reach the End.

Comments

0 comment