views

Prewriting Your Story

Free write about sadness. If you want to write sad stories, you'll have to start by seeking inspiration. Consider what makes you sad. For about 10 minutes, free write on the topic of sadness. Talk about the kind of situations that make you sad. There are a lot of changes that come in life that can make people sad. Friendships and other relationships ending can cause sadness. The death of a loved one can also make someone sad. Sadness can also be caused by more minor events. Losing a family pet can be sad. Having to move to another city can be a cause of sadness. Consider what you think sadness is. What thoughts and emotions do you associate with sadness? As you write, talk about your own personal experiences with sadness. For example, when in life did you feel the most sad? Why? You may be able to use experiences from your own life in a short story.

Seek inspiration. The best way to become a better writer is to read more. If you want to know how to write sad stories, you'll have to read a lot of stories with unhappy themes and plots. Read sad stories. Ask your friends and teachers for recommendations for sad stories. As you read, do so actively. Pay attention to how writers build their stories and characters. How do the stories start? How do they end? Why do you have an emotional response to these stories? Ask yourself these questions as you read. Pay attention to what works in these stories. When writing a short story, you only have a short period of time to get your reader's attention. As you read short stories, pay attention to opening lines. How does the writer get your attention? Where does the story start? Many short stories may start when some of the important actions or events have already occurred. Authors may recount such events in flashbacks or imply them through means like character dialogue.

Learn how to begin a story. If you want to write a story, you'll need to know basic story structure. Stories are made up of exposition, rising action, a climax, falling action, and a resolution. The first parts of the story come with exposition and rising action. Your exposition comes at the beginning of the story. This is where you explain who the main character is and what he or she is doing at the beginning of the story. Exposition should be brief and grab the reader's attention. A story's rising action is the series of conflicts that move the story forward. No story can exist without a problem that needs resolving. In a sad story, there should be an element of tragedy to that problem. For example, maybe your main character is caring for her sick dog. The rising action could include her taking the dog to the vet, finding out the sickness is worse than she thought, and struggling with the setbacks and challenges of her dog's medical needs.

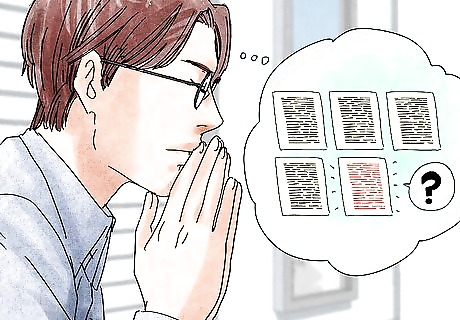

Outline your story. Once you've figured out basic story structure, write a short outline for your story. Write out how your story will begin, what rising action you'll include, the climax, and how the story is resolved. An outline can be brief. It's not necessary to use full sentences in an outline. You just need to have some sense of the basic events that will occur. You can separate your outline into the five elements of story structure: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. An outline should use numbers and letters for structure. Big headings, like "exposition," can be marked with a roman numeral. You can use letters or regular numbers to elaborate on aspects of that heading. For example, "I. Exposition, a. introduce Susan." To help you see how to write an outline, let's return to this article's example. You could begin the outline with something like this: "Exposition, a. Introduce Ada, crying in art class, b. Sad to be reminded of her father's cancer, c. Returns home alone (her mother is at work) to help care for her ailing dog."

Starting the Story

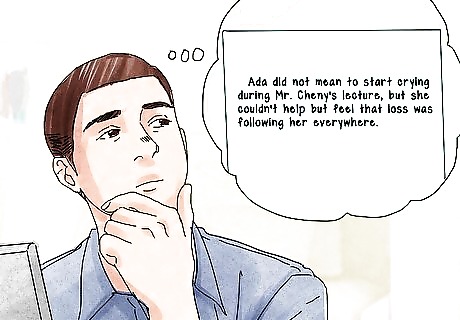

Find a good opening line. An opening line is a vital part of a short story. A good opening line should grab the reader's attention instantly. Readers should go into the story curious, wanting to continue reading. A good first line should establish a strong voice and offer some hint as to what is to come in the story. If you're writing a story centering around themes of sadness, it's important to hint at this in your opening line. If you're stuck, read a few opening lines from your favorite sad stories. You can also Google search something like, "Most memorable opening lines." Read through a variety of opening lines and examine how they function. Why are they successful? Why do you want to keep reading? Take a look at this article's example. In this story, Ada has to eventually accept her dog's death. Let's say her father died of cancer and it's difficult for her to deal with loss. Write an opening line that conveys a sense of coming loss, while also emphasizing past sorrows. For example, "Ada did not mean to start crying during Mr. Cheny's lecture, but she couldn't help but feel that loss was following her everywhere."

Create close relationships within your story. Readers are more inclined to be emotionally moved by strong relationships. This makes sense. Everyone has people in life they are close to. When a story deals heavily with relationships between characters, a reader may experience a stronger emotional reaction. Show how your characters are close. They can finish each other's sentences, help each other without question, and comfort each other during bad times. In this article's example, there are three main characters: Ada, her mother, and her dog. You could write scenes of Ada tenderly caring for her dog, showing how much she loves him. You could also show that's she close to her mother. Ada and her mother could joke lovingly with each other. A brief flashback to Ada's father's funeral could reveal Ada helping her mother cope in the aftermath.

Build up to the main sad event. As you progress through your story, engage with rising action. Build up to the sad event. People are unlikely to be moved by sadness without buildup. If you're not emotionally invested in a character or a situation, you're unlikely to feel sad when reading a story. Each scene in a story should move it forward in some way. Refer to your outline when in doubt. What is your climax? How can you get your characters to this climax? In this article's example, the dog could have a seizure and need to be rushed to the vet. Ada learns the dog's cancer has spread to the brain. Do not just focus on the actions. Pay attention to the emotional story at play. Ada will eventually argue with her mother. You can show her mother gently trying to help Ada brace for the worst case scenario and Ada resisting. As you write these scenes, think about the heart of your story. What is the main point or realization for your characters? Each scene should build up to this point. In our example, Ada may have to accept death is part of life. Try to emphasize inevitable death and decay in each scene.

Write your climax. Once you've written the falling action, focus on your climax. This is the height of action in your story. Try to write a climax that is intense without feeling forced or melodramatic. Remember the character's hopes and dreams at this point. This can help you see what is at stake here. In this moment, what is the character fighting for? What will happen if he or she fails? The best stories have a moment of discovery. This should be somewhat universal. Your character will discover something about herself or her situation that can point to a universal theme or message. In this article's example, the climax is when Ada and her mother fight about having the dog put to sleep. On the surface, what's at stake is the dog's life. On a deeper level, Ada's sense of purpose is at stake. Helping the dog gives her a sense of control over the inevitability of death. A larger realization here could be that accepting death is part of life. Perhaps Ada's mother could say something along these lines during their fight. Levels can benefit sad stories in many ways. In addition to making sad moments feel more intense, readers crave theme and character development. A reader may be more moved by a sad story if he or she feels they learned something along the way.

Choose an appropriate ending. Once you've written your climax, it's time to end your story. A story's ending should offer some kind of resolution to the action. A reader should feel satisfied by the ending, even if it's unhappy. You should not leave your reader with any lingering questions or concerns. You need to build up to your ending with falling action. This is what leads to your conclusion. The main character should make peace with his or her fate. All scenes after the climax should lead to a resolution, serving to lessen the tension rather than build it up. In our example, Ada could have a good cry and then tell her mother she's ready to accept her dog's death. A sad story does not necessarily have to have a sad ending. However, it may feel inauthentic to have things suddenly turn around for your character. If you want to give a sad story a happy ending, make sure you build up to this point. In our example, do not have it suddenly turn out the dog is okay after all. This is not realistic. Instead, maybe it could end a few months in the future. While Ada misses her dog, she has moved on with a new puppy.

Enhancing the Sadness

Avoid melodrama. Melodrama is a common pitfall in sad stories. You do not want your readers to feel like you're trying to force sympathy for your characters. Avoid overwriting tragic descriptions or emotional dialogue. This is often where melodrama creeps in. Melodrama can sometimes be hard to spot, especially if you're invested in a story. In the first draft, you may be desperate to get everything out on the page. It's okay, and even helpful, to overwrite in your first draft. However, when you read your work over for revision, be very strict with yourself. Eliminate any bit of description or dialogue that isn't absolutely vital. Often, less is more when writing a sad scene. If you're describing Ada's dog dying, maybe you could describe this in only one or two sentences. This allows the audience to experience the moment on their own. A certain perspective will not be forced on them. Thinks of your audience's larger perspective, as well. In our modern world, sad stories are all too common. People are at a point where they may be somewhat numb to tragedy that feels generic. There are many stories on the news about death and disease. Zooming in on the emotions of a particular character can help you avoid melodrama. Yes, losing a pet is sad, but why is your character specifically sad? What unique brand of sadness does she feel?

Focus on writing a quality story first. People are often resentful of work that's tragic for the sake of tragedy. People appreciate good storytelling, character development, humor, and dialogue. Remember, your story and your characters come first. The tragedies they experience come second. Really get inside your characters' heads. Establish backstories for your characters that are unrelated to the tragic events they face. Give characters believable personality traits, likes, dislikes, and other quirks. A character should not be defined solely by bad events. Make tragedy feel organic to the story. Do not have the protagonist's mother suddenly drop dead, despite having shown no previous signs of illness. This will feel like a cheap ploy to garner sympathy. If you plan on killing off a character, offer some hints first. Maybe that character is nervous after a doctor's appointment, for example.

Add some humor. A story that's too heavily invested in tragedy can rub readers the wrong way. Many incredibly sad stories offer a great deal of levity along the way. For example, John Green's bestseller The Fault In Our Stars includes a lot of humor while telling a very sad story. The film Steel Magnolias is famous for its fusion of laughter and tears. Look at these works for inspiration on how to use humor.

Remind the reader of the good times during sad moments. As you revise, you'll want to increase the sadness in the story. Comb through your work and look for ways you can increase the emotional intensity. One way to make sad moments sadder is to remind readers of better times. What makes sad moments upsetting is how much they contrast to happier times. This sharp contrast is often jarring. It can strike an emotional chord with readers. When describing a sad scene, add a throwback to a happier moment of your story. For example, say in an earlier scene Ada's dog could make a gurgling noise that sounded like, "Hello." This made Ada and her mother laugh. In a later scene, when the dog is on his deathbed, it could make that noise again. A previous happy noise is now tainted with a sad moment.

Make your audience love your characters. Spend some time reviewing a character's good qualities. People will be more moved by tragedies if the characters involved made a positive impact on others. You can add a few sentences as a character is dying, for example, briefly reminding the reader of the positive impact he had. In our example, you could write something like, "Riley wagged his tail at Ada, still the loving and loyal dog he'd always been."

Draw connections between tragedies. A good way to help enhance sadness in a story is to link your tragedies. Make connections between different sad and traumatic moments. This adds extra emotional impact. In our example, you could easily draw a parallel between Ada's dog's death and her father's death. Ada could feel sad that, once again, she's failed to stop the inevitable. This will make readers feel for the character. She has gone through a lot.

Comments

0 comment